The central purpose of stewarding distinctive collections is to enable scholarly and societal impact. We seek to protect and preserve archives, rare books, and other special collections—work that is in many ways more fraught and more important than ever before. But stewardship is not preservation for its own sake. Rather, its purpose is to ensure that scholarly and public discourse can be meaningfully grounded in primary source materials, so that interpretation, critique, and debate are informed by the most complete evidence possible. Impact is therefore not incidental to stewardship; it is the measure of its success.

Many practitioners have long recognized impact as our purpose, but translating it into clear measures of success—and into day-to-day operations—has not always been simple. To generate impact in today’s digital research landscape, our community must pursue and embrace technologies, platforms, workflows, and methodologies that make discovery and access possible—digitally, and at scale. I recently wrote about how a collections processing tool like JSTOR Seeklight can accelerate and improve description, transcription, and other processing activities in service of discovery and impact when it is thoughtfully adopted in ways that support practitioners’ expertise. In this piece, I focus on another critical element: the digital collections platforms through which libraries and archives enable people to find and use distinctive collections.

My argument is simple: Most library digital collections platforms today are not designed for discovery and access at the level today’s research environment demands. Digital collections frequently remain unnecessarily isolated from the research workflows, discovery practices, and preferred platforms embraced by scholars and students—and are therefore underused relative to their potential. In what follows, I outline what modern discovery requires, why platform choice now shapes impact, and what we should demand of the platforms that make distinctive collections available.

Digital access is necessary but insufficient

Over the past several decades, as research has become increasingly digitally mediated, the spaces of scholarly discovery have transformed dramatically. Through this transformation, scholarly publishing has prioritized full-text digital access—e-books and electronic journals alongside tangible collections, increasingly in digital-first formats. Today we are moving through a second digital transformation, which includes a fundamental reshaping of researcher expectations: from anywhere, a student or scholar can not only discover that something exists, but engage with it in full. Yet, primary sources have yet to benefit from an equivalent transition at scale.

My argument is simple: Most library digital collections platforms today are not designed for discovery and access at the level today’s research environment demands. Digital collections frequently remain unnecessarily isolated from the research workflows, discovery practices, and preferred platforms embraced by scholars and students.

Even as the digitization of distinctive collections has proceeded, many remain far less visible at the item level, and far less integrated into the platforms where researchers begin their work. The result is a persistent gap between the discoverability of secondary literature and the discoverability (and usability) of primary sources—which limits the impact these materials can have.

To be sure, collection stewards have taken meaningful steps in addressing this gap. One major avenue has been encoding, publishing, and aggregating finding aids, so researchers can discover that a collection exists and understand its scope. Many key functions historically served by finding aids (including conveying context, provenance, and intellectual order) remain essential. But in digital research environments, those functions may no longer need to be carried by a single documentary form. They can be complemented by discovery that draws directly from the materials themselves—not just descriptions of them.

For this reason, many institutions have worked to bring digitized and born-digital collections online and improve how they can be found and used. This begins with processing work—description and transcription among the core activities—which can be made more effective and efficient with modern tools, as I argued in my previous piece on collections processing. But processing materials for digital use and making them available online is only part of the equation. The degree to which collections generate impact also depends on where and how they are made discoverable.

Search remains foundational

The job of any discovery and access platform for digital collections is to connect a user to the best content at the right time. In this and several following sections of this piece, I will review the elements necessary to do this, beginning with search. Although search is absolutely foundational to discovery, it can seem interchangeable across platforms. In reality, though, outstanding search is an area of enormous differentiation.

Today’s best discovery environments offer search that is far more sophisticated than simple keyword frequency. They help users navigate abundance through relevance, relationships, context, semantics, and a range of other discovery modes.

Ideally, search enables multiple points of entry into a given collection. The extent to which this is possible depends on how the collection is processed —for example, whether materials carry item-level description, recognized full-text and transcriptions, and so forth. With these foundations, users can find relevant materials even when their searches are not “about” a collection as such. Item-level description can now feasibly provide points of entry and connections across materials (for example, on contributors, topics, and forms of cultural and political expression) that were previously unattainable.

There is a risk as well. A search that covers item-level description and full-text—including handwritten materials—can feel overwhelming if it is not well supported by the platform. But today’s best discovery environments offer search that is far more sophisticated than simple keyword frequency. They help users navigate abundance through relevance, relationships, context, semantics, and a range of other discovery modes.

Discovery is more than search

Search is powerful, but discovery is more than search in the traditional sense. It includes integration with secondary literature, recommendations and alerting, curation and exhibitions, tools for analysis, and collections context, among other elements. These modes of discovery are increasingly familiar expectations—shaped by the systems we all use in everyday life.

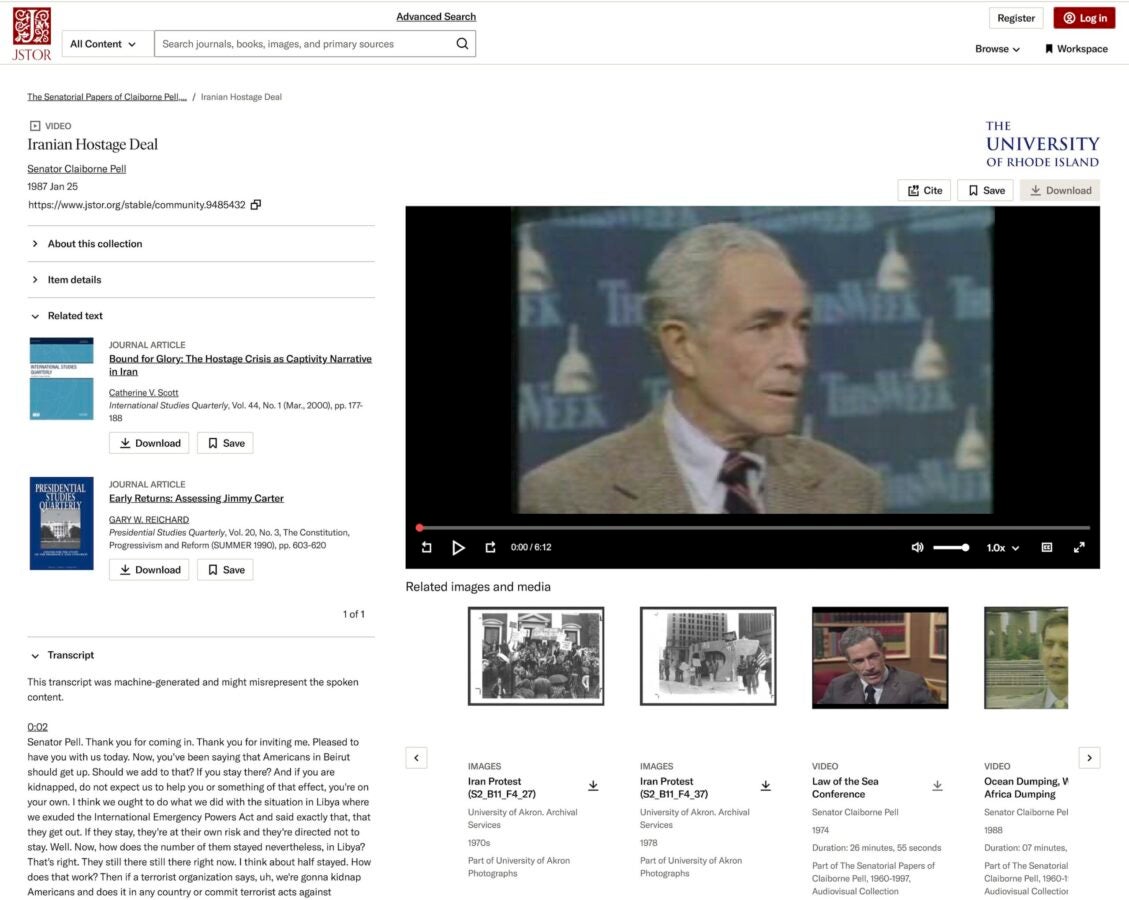

Discovery deepens when secondary literature and primary sources are integrated. In the scientific and quantitative fields, there are growing efforts to link datasets with journal articles. For the humanities, arts, and social sciences (HASS), the parallel opportunity is bi-directional linking of archival and special collections materials with critical context and analysis in scholarly monographs and journal articles. This is more than “linking” in a simple sense: it enables context-driven discovery that supports deeper exploration and interpretation, rather than more atomized access to discrete items.

Recommendations and notification features are also powerful vehicles for discovery. These can include platform-generated recommendations, sometimes customized to a specific user and sometimes based on content relationships. They can also include alerting mechanisms—for example, notifications when new items related to particular concepts, keywords, or themes become available.

There’s also great potential in tools for curation and exhibition. These can support the creation of sets of materials—for example, by an instructor, curator, or scholar—and enable them to be shared privately with a class, or more broadly. Sometimes these sets are organized into syllabi or reading lists; in other cases they take the form of a virtual exhibition or digital humanities work. In each case, the point is enabling discovery that goes beyond retrieval—by adding context, surfacing connections, and arranging materials in ways that support teaching and scholarship.

For archival collections in particular, context is vital but has often been insufficiently represented in online tools. The ability to connect an item back to the broader collection in which it is housed—and to represent the hierarchical relationships between collections, series, and items—adds meaning that can otherwise be lost. This challenge is not new: microfilm projects often serialized items within a collection on a single reel, flattening context in the process. Today, a well-designed digital platform can do far better—providing strong connections between an item (with item-level description) and a higher level of hierarchy (such as a folder or a collection, the latter with a well-crafted finding aid), and thereby providing researchers with a strong sense of collection context, as well as the links that make possible effective navigation within a collection.

Discovery requires scale

These modes of discovery—deep interconnections with the secondary literature, recommendations and alerting, curation, and exhibitions—can dramatically expand the impact of distinctive collections. But they depend on a critical propellant: scale. Without a broad and deep corpus of materials and context, these modes of discovery are almost impossible to realize. With such scale, they can become incredibly powerful for users.

Many institutions, however, rely on institution-specific platforms—whether hosted on premises or through cloud offerings—to make their digital collections available. To be sure, some see benefits in this approach, for example, in bringing together institutional repository materials with digital collections through a single platform. And institutional systems increasingly support metadata sharing for aggregation and search elsewhere.

These modes of discovery—deep interconnections with the secondary literature, recommendations and alerting, curation, and exhibitions—can dramatically expand the impact of distinctive collections. But they depend on a critical propellant: scale.

But institution-specific platforms limit scale—and therefore impede discovery and impact. They silo collections based on institutional holdings, resulting in a corresponding fragmentation of engagement, impeding users’ ability to encounter and interpret collections together. As a result, many of the most compelling discovery opportunities for distinctive collections in the digital environment are, as yet, unrealized.

At the same time, scale cannot come at the expense of institutional control and stewardship. Institutions want to maintain ownership of their collections and exercise control over how they will be digitally delivered and under what terms (including AI training rights). One early and enduring goal of digital collections work was to showcase the holdings of a given institution, and for that reason institutional branding has often been a foremost concern. Understandably, most institutions want credit for sharing collections publicly—and a say in how they appear. Many libraries (and publishers) selected institution-specific instances at a time when that seemed like the only way to exercise strong institutional control and ensure appropriate institutional branding.

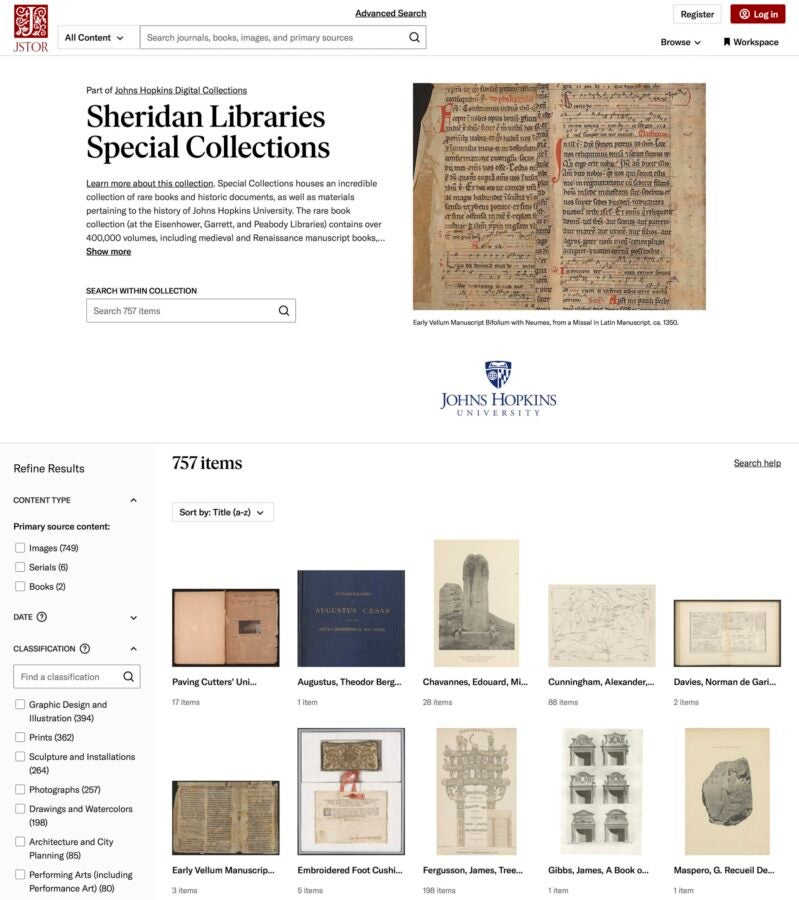

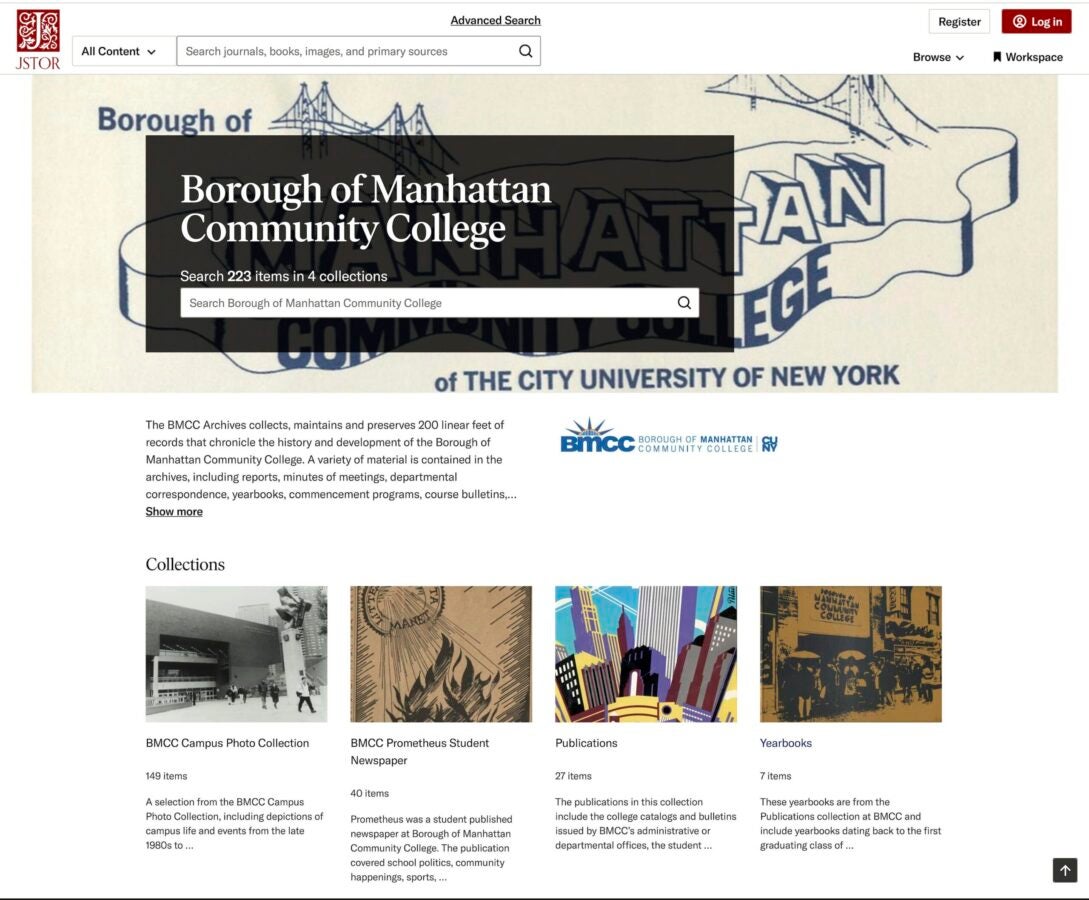

There is, however, another model: a platform that brings together distinctive digital collections from multiple institutions, while ensuring institutional stewards retain ownership and providing meaningful institutional visibility. An institutional landing page, visual identity, and other forms of representation ensure strong institutional branding—without sacrificing the discovery advantages of cross-institutional scale. Institutional priorities and cross-institutional scale are thus entirely complementary, enabling today’s choices to be grounded in a commitment to discovery and impact.

Research workflow

A cross-institutional platform for digital collections can expand discovery, but this is not enough by itself. To maximize discovery and impact, distinctive collections must also be discoverable within existing research workflows.

A platform that sits within the research workflow has a number of key distinguishing elements. Researchers recognize it and return to it. Links to it frequently appear in syllabi, citations, and course materials. Libraries provide extensive instruction in how to use it. It is discoverable through the wider ecosystem—library discovery layers, Google Scholar and other search environments—and it earns sustained, measurable use over time.

Ultimately, the opportunity is to think about digital collections as parts of the research literature—not separate from them—while enhancing (rather than supplanting) institutional stewardship of them.

Building a platform that is integrated into the research workflow requires years of cultivation, and those that achieve this level of ubiquity have typically been built around materials that researchers already rely on at scale, such as journal literature, books, and newspapers. Several are situated primarily within the STM ecosystem. For most distinctive collections, research platforms that focus on HASS communities are probably more relevant.

Incorporating library digital collections into a research platform has a number of compounding benefits. It ensures the distinctive collections can be discovered within the existing research workflows of key user communities—both at one’s own institution and well beyond it.

Perhaps just as significantly, doing so enables us to situate distinctive collections alongside the scholarship that studies and contextualizes them—such as journal articles and humanities monographs. This can provide vital context, particularly for undergraduates but also for scholars, not only through linking sources but also through recommenders and other more serendipitous means.

Ideally, any such research platform will have a strong commitment to maximizing free and open access. This is particularly important for published materials that are co-located with distinctive collections, to serve unaffiliated researchers and the general public to the greatest extent possible.

Ultimately, the opportunity is to think about digital collections as parts of the research literature—not separate from them—while enhancing (rather than supplanting) institutional stewardship of them.

What to demand of digital collections platforms

In selecting a digital collections platform, many libraries and archives have emphasized the features needed by librarians and archivists for processing and managing collections. These characteristics remain essential, but incomplete. If discovery and impact are the goals, then libraries selecting a digital collections platform need to consider how the platform addresses these goals.

I offer here a checklist of some of the characteristics that a library might incorporate into its selection process for such a platform:

- Powerful modern search. As more distinctive collections become digitally available (with robust item-level metadata and recognized text and transcriptions), the platform should provide search that connects users to the right materials.

- Discovery beyond search. The platform should provide modern services such as integration with secondary literature, recommendations and alerting, curation and exhibitions, tools for analysis, and collections context.

- Cross-institutional scale without sacrificing institutional stewardship. The platform should have enough scale to “generate its own gravity,” integrating distinctive collections from numerous libraries and archives, while ensuring ongoing ownership, control, and branding from stewarding institutions.

- Strong integration into existing research workflows. The platform should be familiar to one’s own students and relevant researchers, regularly included in library instruction for HASS courses so that its interface and features are broadly understood, and widely used beyond one’s institution, with substantial activity from students and HASS scholars at other universities.

Sharing one’s digital collections through a platform with these characteristics enables stewarding institutions to achieve their purpose of discovery and impact in a modern research environment.

What JSTOR can offer

For thousands of institutions and millions of researchers worldwide, JSTOR already functions as a familiar starting point for research in the humanities, arts, and social sciences. That familiarity, combined with sustained investment in discovery, creates an opportunity: to bring distinctive collections into closer proximity with the scholarly materials and workflows that shape interpretation and teaching.

Through JSTOR Digital Stewardship Services, libraries and archives can make their collections available on JSTOR—either while retaining an existing digital asset management environment or by using JSTOR Stewardship as the primary system for processing, managing, preserving, and sharing digital collections. In doing so, institutions can make real gains in discovery today, while also contributing to a longer-term direction: a shared discovery-and-use environment in which distinctive collections are easier to find, contextualize, and reuse.

If you’d like to explore how to maximize the discovery and impact of your distinctive collections, you can learn more about JSTOR Digital Stewardship Services.