This resource was adapted from Carson Smith’s original guest blog post contribution, which can be found here.

Why slow art matters

In introductory art history courses, many students are encountering artworks for the first time—not as aspiring art historians, but as engineers, nurses, or computer science majors who may never have visited a museum.

Teaching art history… is a balancing act: instructors like myself should be able to present relevant artistic and art historical theories, knowledge, and methods while also keeping students engaged.

In an era when students consume hundreds, if not thousands, of images a day, their visual attention is fragmented. They scroll, skim, and swipe past the very visual materials that art history asks them to linger with.

This resource introduces “slow looking” as both a pedagogical tool and a research skill: a way to help students differentiate between image and artwork, perception and reality—and to experience the depth, context, and emotion embedded in visual form.

Teaching students and encouraging them to relate to artworks, and to engage with visual media in a more methodical way is key to keeping students interested, and to giving them the skills to slow down and combine visual and conceptual ways of thinking. These skills are very much translatable to other courses, majors, and career paths.

Designing the Slow art project

Smith developed the Slow art project to help students engage with artworks on a deeper, more analytical level, inviting them to look slowly, think visually, and collaborate creatively.

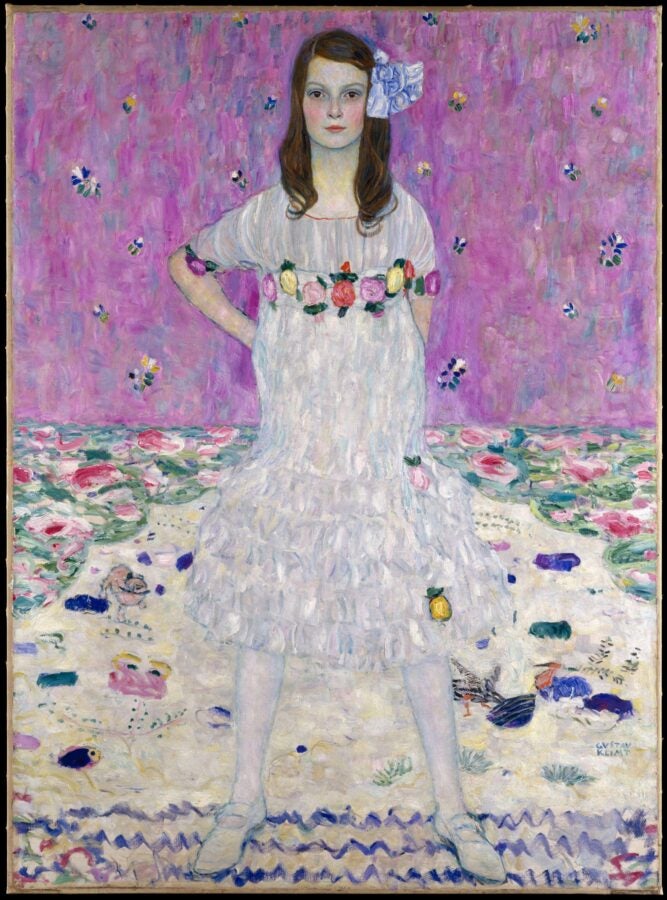

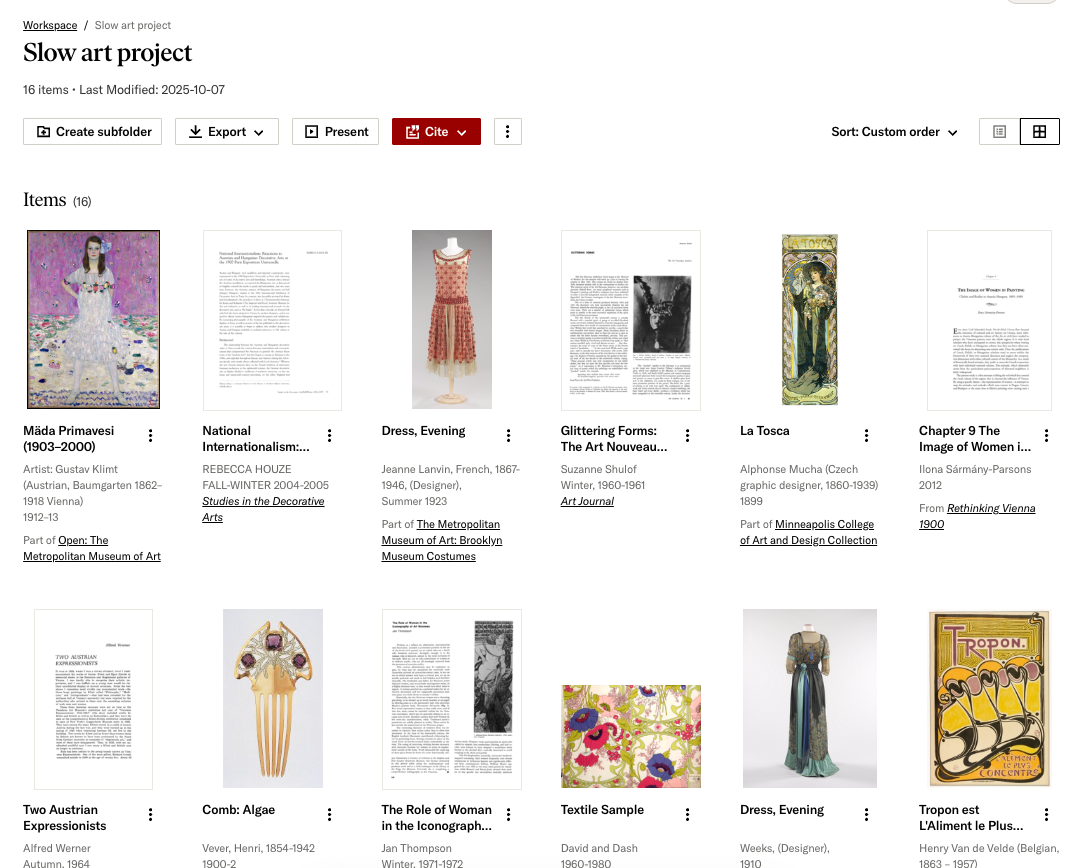

In this assignment, students create a mock museum or gallery exhibition using materials from JSTOR and Open Artstor on JSTOR. Working in pairs or small groups, they research an artist, select works, and organize their findings around a shared theme such as organic form, craftsmanship in high art, or the relationship between art and technology.

By combining scholarly sources from JSTOR with images from Open Artstor, students practice methods of visual and formal analysis, thematic interpretation, and curatorial thinking.

The project also speaks to a key generational insight:

This project is specifically a way for “Gen Z” and other digitally aware students, who are among the first generation of “digital natives,”1 to engage with art historical theories, ideas, and methods with their specific learning styles in mind.

Try the Slow art project in your classroom

Step 1: Choose your theme

In groups of 2-3 students, choose a shared idea or theme–visual, cultural, or theoretical–from a relevant unit (e.g., Art Nouveau, Baroque, Modernism).

Step 2: Research and curate using JSTOR

Create a free personal JSTOR account if you don’t already have one.

Use Open Artstor to browse available works related to your theme. Identify 1-3 images from a single artist that captures your group’s shared idea, and save them to your personal Workspace. Consider:

- Why were you drawn to the movement or works you selected?

- What stuck out about these works specifically over other works by the same artist(s)?

- Is there a specific visual or thematic element of the works that drew you to them?

- What connection do your chosen works have to reading and/or lecture material from class?

Using JSTOR, search for at least 1 supporting journal article, book chapter, or other relevant scholarly source related to your group’s theme or your selected artist. Save your scholarly resource(s) to your Workspace as well, and consider how this supporting content informs your understanding of the works you selected.

Step 3: Build your exhibition

Each student should contribute at least one artwork and one scholarly resource to your group’s exhibition.

As a group, prepare:

- Artist biography slide(s), one per artist.

- Artwork slide(s) including:

- Identifying details: artist, title, medium, and date.

- 50-100 words of “wall text” describing each work’s significance and its connection to your shared theme. Learn more here about writing a wall text.

- A shared bibliography of all sources used in your presentation. Note that JSTOR provides auto-generated pre-formatted citations in a variety of citation styles for individual items.

Step 4: Present your exhibition

Groups deliver a 5-10 minute presentation addressing:

- Why the chosen works resonate.

- How each relates to your central theme.

- What insights emerged from scholarly readings.

Encourage students to go beyond surface-level similarities:

This should go beyond simply stating ‘these pieces are all thematically tied because they’re part of the same movement.’ How does that movement group these artworks? How are these specific artworks related beyond surface level observation? This is where any academic resources saved to their Workspace will be utilized.

Keep going: Extend the Slow art project

Once students have completed their mock exhibition, there are several ways to deepen their engagement and connect this work to broader art historical and interdisciplinary contexts:

- Host a “slow art” day: Dedicate a class period to observing and discussing a single artwork in depth, either online or on-site at your university museum, library’s special collections, or local museum.

- Connect with other disciplines: Collaborate with educators in media studies, computer science, or psychology to explore how visual perception, algorithms, and attention shape how we experience art today.

- Add reflective writing: Ask students to journal about how their perception of art changed through this process. How did “slowing down” affect their understanding of visual media?

- Create a class anthology: Compile group exhibitions and wall texts into a shared digital collection or publication to celebrate student scholarship.

1John A. Huss, “Gen Z Students Are Filling Our Online Classrooms: Do Our Teaching Methods Need a Reboot?,” InSight: A Journal of Scholarly Teaching 18 (July 2023): 101–12, https://doi.org/10.46504/18202306hu.

Get involved

01

Sign up for email updates

You’ll receive occasional communications with new resources, educator success stories, and webinars and events—all designed to support your teaching.

02

Share your expertise

We invite educators to work with us to create teaching resources for the academic community.

03

Join our growing LinkedIn community

A global community of educators shares best practices and fresh ways to boost student engagement.