Remember field trips?

Stepping out of the classroom and into another world—seeing lessons come alive beyond textbooks—was one of the best parts of learning. But field trips don’t have to end in childhood, and they don’t have to involve leaving the classroom.

With Artstor on JSTOR’s collections and JSTOR’s tools, educators can take students on virtual field trips using only a laptop. These guided explorations bring the world into your classroom, promoting equity, engagement, and visual and digital literacy—without the logistical barriers of traditional field trips.

I’ve used Artstor and JSTOR virtual field trips in my own courses to change up the classroom dynamic, inspire curiosity, and make complex topics accessible. Here’s how you can, too.

Designing a virtual field trip

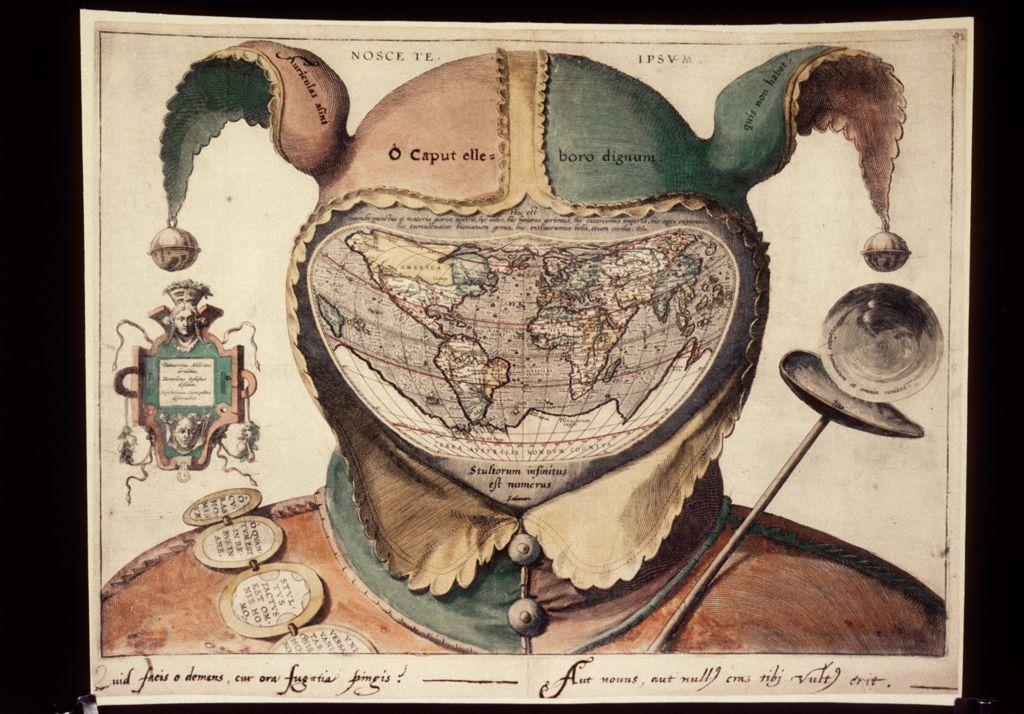

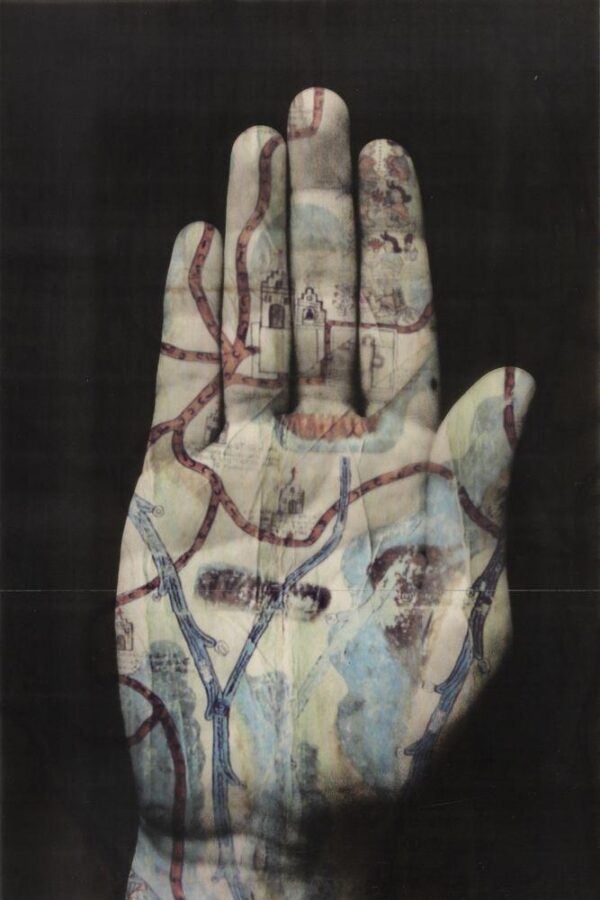

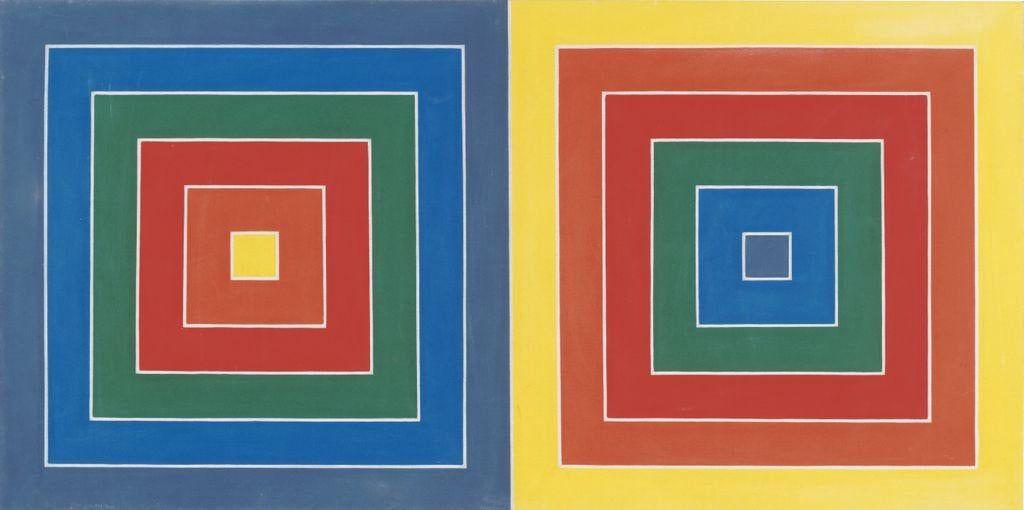

A virtual field trip is a guided learning exercise that brings the world into your classroom—no travel required. Using a digital archive like Artstor on JSTOR, students can explore primary sources, artworks, and artifacts while completing structured tasks that encourage them to look closely, think critically, and connect course material to the wider world.

To design an effective virtual field trip, start with a clear prompt that guides discovery:

- Choose your archive: Pick collections that align with your course theme or topic.

- Guide the experience: Offer clear instructions for navigating Artstor on JSTOR (see our guide to Artstor on JSTOR for tips).

- Prompt reflection: Include open-ended questions students can discuss individually, in small groups, or as a class.

- Encourage connection: Ask students to relate what they discover to readings, lectures, or personal experience.

See the sample virtual field trip prompt at the end of this resource to get started.

How virtual field trips support learning

Virtual field trips foster visual and digital literacy, core skills that enhance critical thinking across disciplines.

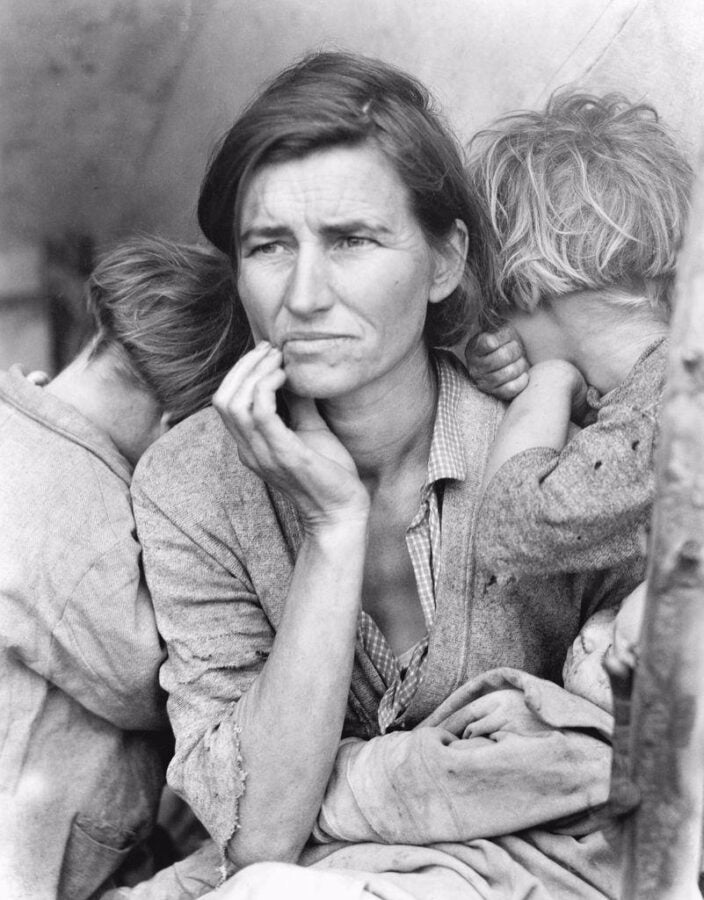

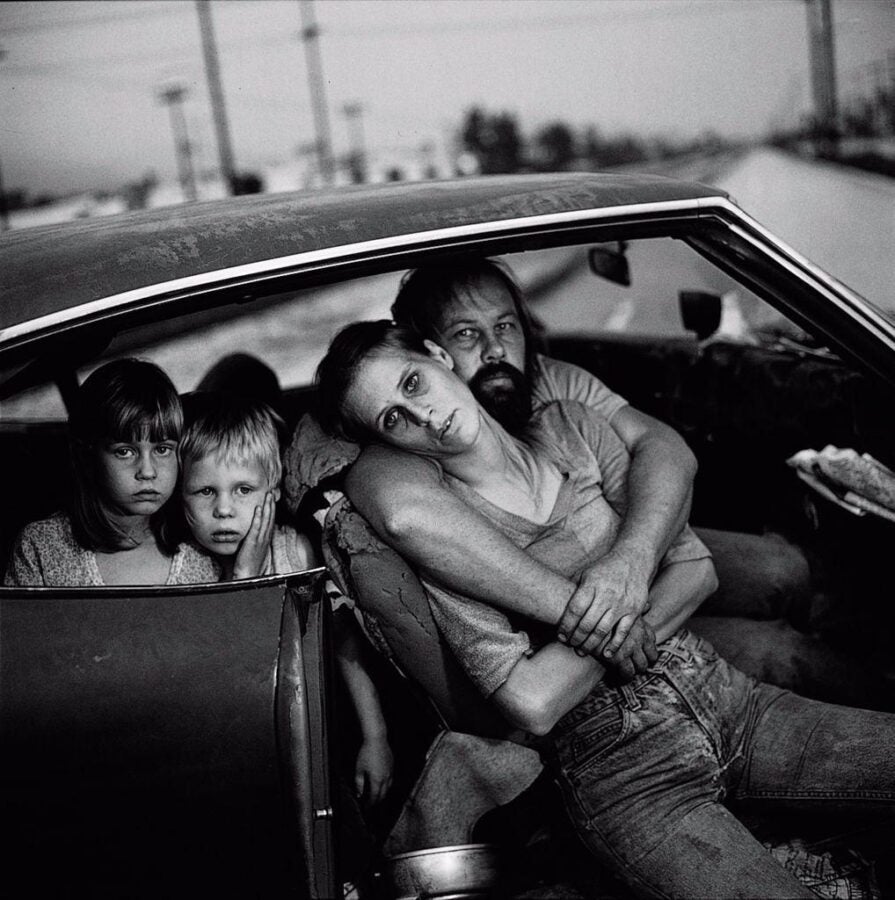

Visual literacy helps students interpret and analyze imagery, something they do constantly on social media but rarely in an academic context. By practicing slow, intentional observation, they learn to extract meaning, question context, and connect visual culture to broader ideas. As Virginia Seymour explored extensively in her Learning to Look column on JSTOR Daily, there are creative ways to engage with visual literacy in every discipline. Seymour even provides a range of lesson plans to help students cultivate visual literacy. These plans also include hands-on guides to support students in their image-based projects.

Digital literacy involves finding, evaluating, and communicating information responsibly. Using Artstor on JSTOR exposes students to authentic, rights-cleared images and reliable metadata, helping them distinguish scholarly resources from unverified content found elsewhere online.

Equity and engagement in action

Virtual field trips remove common barriers to experiential learning: no travel costs, scheduling issues, or accessibility hurdles. Every student can explore from the same starting point, with equitable access to the same high-quality materials.

They also meet students where they are. Research shows Gen Z learners thrive when they can see and do—connecting abstract ideas to concrete examples. By incorporating Artstor’s rich imagery into assignments, educators tap into students’ visual fluency while keeping learning active, relevant, and hands-on.

When I introduced virtual field trips in my classroom, student feedback highlighted increased engagement, creativity, and confidence. The format gave them space to pursue personal interests within academic frameworks, turning passive observation into genuine discovery.

Try it for yourself: A sample virtual field trip prompt

Objective: Encourage students to practice visual analysis and connect artworks to course themes.

- Provide students with a list of keywords drawn from a recent lecture or reading.

- Have them search one keyword on JSTOR, filtering results by “image.”

- Ask each student to save five images that capture their attention using JSTOR’s Workspace feature. They’ll just need to create a free personal account first.

- In Workspace, students should read the image details and choose one or two that resonate most. Ask:

- What drew you to this image?

- What story does it tell?

- How does it relate to our course theme or reading?

- In small groups, students share findings and discuss similarities and differences in interpretation.

- Wrap up with a brief written reflection linking their chosen images to class concepts.

This adaptable exercise works well in art history, anthropology, history, political science, and other liberal arts disciplines.

Get involved

01

Sign up for email updates

You’ll receive occasional communications with new resources, educator success stories, and webinars and events—all designed to support your teaching.

02

Share your expertise

We invite educators to work with us to create teaching resources for the academic community.

03

Join our growing LinkedIn community

A global community of educators shares best practices and fresh ways to boost student engagement.