Uncover hard-to-find academic materials with ease

Available through OpenAI’s platform, the JSTOR’s Conversational Discovery is a research pilot designed to help us learn how you use ChatGPT to uncover credible academic scholarship, accelerate your discovery, and strengthen your research skills.

A responsible approach to research in the age of AI

As researchers increasingly begin their work with the help of chat-based AI tools, the JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT, currently in beta, ensures that trusted scholarship remains easy to find and use responsibly. We are running this pilot to explore how trusted scholarship remains accessible in the age of AI. Your participation helps JSTOR learn how to build tools that empower—not replace—researchers. Every interaction helps us refine how we ground AI recommendations in our verifiable scholarly corpus.

Just like JSTOR’s on-platform AI tools, the JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT:

- Helps guide and coach research skills

- Draws from JSTOR’s trusted corpus of journals, books, and research reports

- Provides verifiable results, including direct URLs and citations to actual JSTOR content

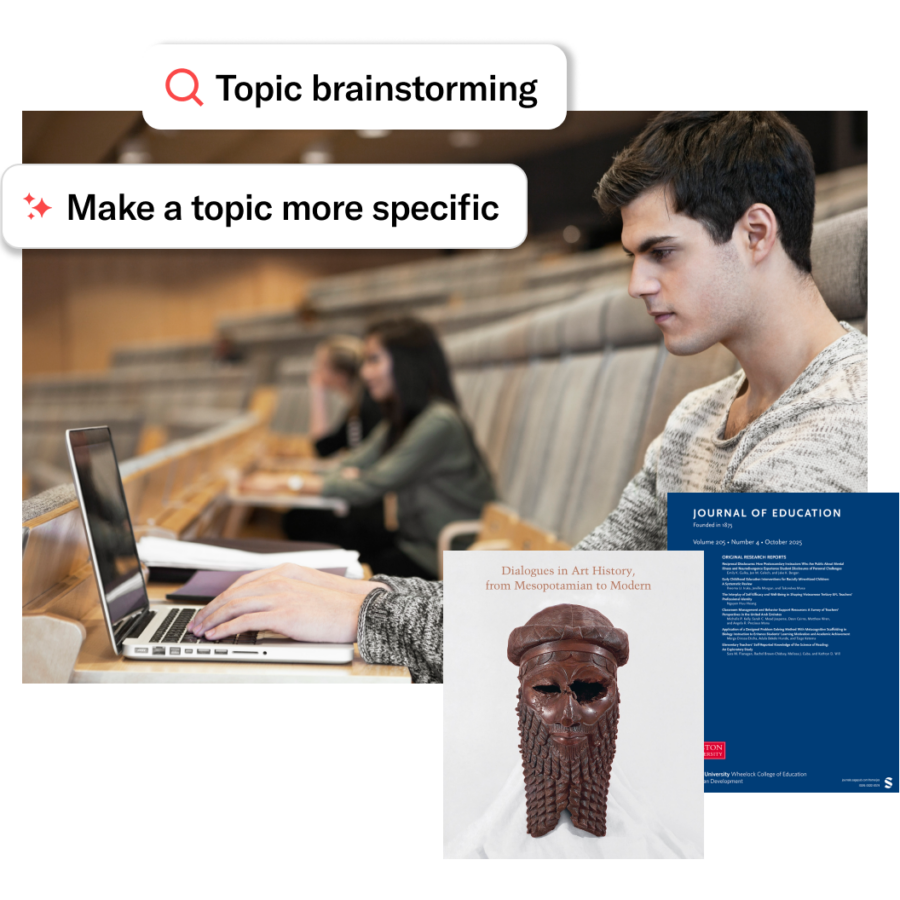

A chat-based research accelerator

The JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT connects directly to JSTOR’s search infrastructure, letting you use natural language to conduct research, refine questions, and accelerate discovery within a trusted academic environment.

Search & discovery

- Ask a question: Type what you want to learn about in your own words

- Explore results: See overviews, article titles, and topics drawn from JSTOR’s academic library

Research coaching

- Refine questions: Brainstorm and refine complex research questions

- Advanced queries: Learn how to build stronger searches using fielded/Boolean logic

Document analysis

- Upload documents: Analyze your papers or theses to find related JSTOR sources

- Discover connections: Identify relevant scholarship based on your document content

Ready to explore?

Frequently asked questions

What data sources does the JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT use?

The JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT draws exclusively from JSTOR’s scholarly corpus—the same journals, books, and research reports available through JSTOR.org. The tool uses JSTOR’s dedicated search APIs, including GPT-specific endpoints, to surface overviews, citations, and links grounded in real, verifiable JSTOR content.

Is full-text content available to JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT?

No. The JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT relies only on item metadata and short overviews. To read the full text, users need to visit JSTOR.org.

How is my information kept, shared, and/or used?

Users who have the “Improve the model for everyone” option turned on in ChatGPT should be aware that their conversations may be used by OpenAI to train its models.

When using the JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT, JSTOR only uses your queries to retrieve metadata from our collections so the tool can generate a response. Once you move to JSTOR.org, your activity is handled under JSTOR’s existing privacy policy.

JSTOR does not sell user data, and we do not share JSTOR content or user information with third parties for training external large language models.

Is the JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT free?

Yes, using the JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT is free. The JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT is currently offered as an experimental, early-stage research experience available inside ChatGPT. Access to full-text articles on JSTOR continues to follow our standard access model—through your library, institution, or individual account, where applicable.

How is the JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT different from the AI-enabled features on JSTOR.org?

The JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT helps you brainstorm research questions, explore ideas, and discover relevant JSTOR content using conversational language.

JSTOR’s on-platform AI research tool is more document-centered. It helps you understand the usefulness of a specific item through short overviews, key topics, and the ability to ask targeted questions to evaluate it more effectively.

Both tools complement each other. Searching directly on JSTOR.org is also an option, and we’re adding more brainstorming and natural-language search capabilities to the JSTOR platform as we go. The goal is to make JSTOR’s scholarly content available wherever you begin—whether that’s a search engine, AI platform, or JSTOR.org.

When should I use the JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT?

The JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT is ideal for the early stages of exploring a topic as it can provide a quick, intuitive way to discover relevant materials. It’s great for:

- Brainstorming research questions

- Getting suggestions for search terms or advanced queries

- Finding related JSTOR content based on an uploaded document

- Navigating unfamiliar subjects in a natural, conversational way

The JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT acts as a helpful guide to get you started, then directs you to JSTOR.org to read or access the full content. There, you can use JSTOR’s on-platform AI tools to continue your research.

When should I use JSTOR’s on-platform tools?

Use the tools on JSTOR.org when you’re ready to do deeper academic work—reading, analyzing, citing, and engaging directly with scholarly materials. Our on-platform tools have several advantages over the JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT for detailed work:

- Access to full-text content (based on your subscription or institutional access)

- Richer metadata, filters, and search controls

- Support for scholarly provenance and citation

What are some limitations of JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT?

Although the JSTOR Conversational Discovery GPT relies on JSTOR Search API and the JSTOR corpus, it is powered by ChatGPT, which means it can occasionally generate inaccurate or invented details. Links to the original JSTOR articles are provided, so users can review the full sources themselves. Additionally, not all publisher content is available through the tool, so certain materials may be missing from results.

Advancing research with responsible AI

Discover stories, insights, and tools that show how JSTOR is using AI responsibly to support equitable, trustworthy academic discovery.

Sign up for updates

Never miss a thing. Get updates from JSTOR delivered straight to your inbox.

By signing up you agree to our Privacy Policy. You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

"*" indicates required fields

View image credits from this page

Lydia Collins. “The Private Tombs of Thebes: Excavations by Sir Robert Mond 1905 and 1906.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 62 (1976): 18–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/3856342.

James P. Ronda. “‘A Knowledge of Distant Parts’: The Shaping of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 41, no. 4 (1991): 4–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4519424.

F.G. Young. “The Higher Significance in the Lewis and Clark Exploration.” The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 6, no. 1 (1905): 1–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20609635.

Hessel Miedema. “Johannes Vermeer’s ‘Art of Painting.’” Studies in the History of Art 55 (1998): 284–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42622613.

“THE LEWIS AND CLARK EXPEDITION.” The Journal of Education 59, no. 15 (1475) (1904): 230–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44058779.

Huigen Leeflang. “Dutch Landscape: The Urban View: Haarlem and Its Environs in Literature and Art, 15th-17th Century.” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 48 (1997): 52–115. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43888510.

Deborah Allen and Deborah J. Allen. “Acquiring ‘Knowledge of Our Own Continent’: Geopolitics, Science, and Jeffersonian Geography, 1783-1803.” Journal of American Studies 40, no. 2 (2006): 205–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27557790

Adam Jones and Isabel Voigt. “‘Just a First Sketchy Makeshift’: German Travellers and Their Cartographic Encounters in Africa, 1850-1914.” History in Africa 39 (2012): 9–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23470997.

James A. Welu and Vermeer. “The Map in Vermeer’s ‘Art of Painting.’” Imago Mundi 30 (1978): 9–2. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1150701.

Benjamin Schmidt. “Mapping an Empire: Cartographic and Colonial Rivalry in Seventeenth-Century Dutch and English North America.” The William and Mary Quarterly 54, no. 3 (1997): 549–78. https://doi.org/10.2307/2953839.

Tamara Bellone, Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro, Francesco Fiermonte, Emiliana Armano, and Linda Quiquivix. “Mapping as Tacit Representations of the Colonial Gaze.” In Mapping Crisis: Participation, Datafication and Humanitarianism in the Age of Digital Mapping, edited by Doug Specht, 17–38. University of London Press, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv14rms6g.9.

Handwritten class notes. Image generated by Gemini 2.5 Flash Image (Nano Banana), Google, December 17, 2025, via Figma.