Expectations for digital access to archival materials are rising, even as staffing and budgets for the necessary descriptive work remain flat or decline. While new technologies—including general-purpose AI tools—offer some promise for accelerating metadata creation, these tools can introduce risk without delivering trustworthy, repeatable workflows at scale. Typically, you can only process up to 10 files at a time with any amount of confidence that the metadata it generates is accurate.

This was the dilemma facing Goldey-Beacom College (GBC), a small, primarily undergraduate institution in Delaware with a career-focused, affordability-driven mission. GBC’s library held a rich but under-described archive: millions of photos and documents had little to no metadata, meaning even digitized items were difficult to find, access, or use. Early experiments with commercial AI tools were underwhelming—discovery was a challenge without rich metadata.

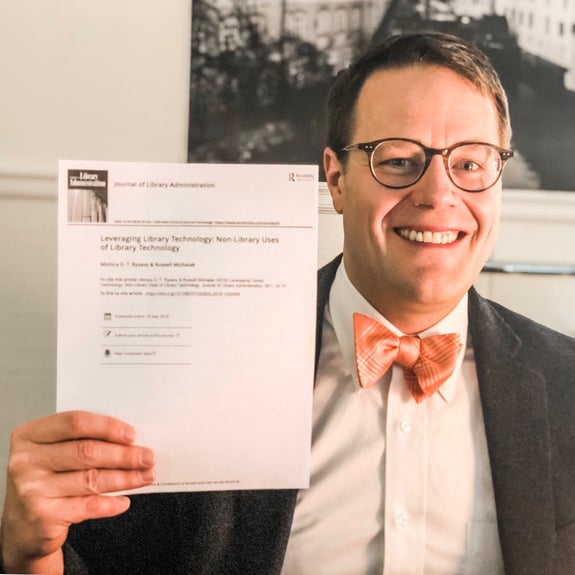

By partnering with JSTOR Digital Stewardship Services and adopting JSTOR Seeklight—an AI-assisted collections processing tool purpose-built for archival work—Director of Library and Archives Rusty Michalak and his student team found a different path. Through combining accelerated metadata creation with human oversight, they developed a workflow that makes previously hidden collections discoverable, keeps judgment in human hands, and turns student employment into hands-on AI literacy training.

As library leaders everywhere weigh similar tradeoffs, GBC’s guiding principle—“AI drafts, people decide”—offers a realistic model for balancing access, care, and learning.

The challenge: A rich archive, limited discoverability

Like many institutions, GBC’s library has experienced a gradual decline in staffing levels over time. Prior to Rusty’s arrival in 2011, the archives had received only intermittent professional attention, most notably from a consultant in 1991. The college has never employed a dedicated archivist, and instead, responsibility for the collections rested with a single librarian supported by a rotating group of part-time student workers. While legacy finding aids were later digitized, the underlying archival materials lacked item-level metadata, limiting contemporary discovery and internal clarity.

Prior to the adoption of dedicated digital asset management systems, materials were often stored on general-purpose platforms such as cloud file servers, where uploading was easy, but descriptive metadata was inconsistent or absent. Even after the initial migration to a proprietary DAM, discovery remained limited because most items—particularly images and ephemera—were searchable only at the box or title level. This required users to manually browse collections until the later transition to a different commercial DAM enabled item-level metadata remediation by student workers.

At the same time, Rusty had a dual responsibility:

- As a collection steward, he was committed to expanding access to the college’s holdings in ways that were responsible and sustainable.

- As a student employer, he was equally committed to preparing undergraduates for the workplace—equipping them with practical skills, including fluency with emerging AI tools and ethical decision-making.

In an early experiment using AI to advance these goals, two student interns described 250 images for a microhistory book project by manually writing metadata, enhancing it with a commercial LLM, and verifying every record by hand. Even with AI augmentation—and 20 hours per week, per student—the project took nearly a year. Attempts to scale reduced quality. At that pace, processing the full archive would take decades.

The takeaway was clear: item-level description was essential, but general-purpose AI could not scale archival work while maintaining trust and consistency. What the library needed was a way to move faster without taking on new risk—and ideally, a way to make the work itself a teaching opportunity.

The solution: A trusted partner and guardrailed workflows

When Rusty learned about JSTOR Seeklight, he immediately recognized alignment with what he had been trying to build—now supported by a library-centered partner with workflows designed for archival practice.

“We were trying to scale our work with AI before, but we didn’t have a trusted partner,” he said. “Having a trusted partner like JSTOR is key.”

We were trying to scale our work with AI before, but we didn’t have a trusted partner. Having a trusted partner like JSTOR is key.

Developed in collaboration with librarians and archivists, JSTOR Seeklight supports collections processing at scale, while preserving institutional control through built-in review workflows.

At GBC, Rusty and an undergraduate intern piloted Seeklight on 172 archival photographs, testing a human–AI workflow built on four elements:

- Structured context inputs: The student uploaded photographs to JSTOR Seeklight alongside contextual notes that helped the tool understand the collection’s purpose and boundaries—and reinforced better prompting habits for students learning to use AI critically.

- “AI drafts, people decide”: JSTOR Seeklight generated first-pass descriptive metadata, but students were empowered to review, correct, and approve outputs in collaboration with Rusty. Automation handled repetitive drafting humans retained authority.

- Clear guardrails and smart review: To balance rigor with efficiency, Rusty introduced simple, teachable guardrails. Using JSTOR Seeklight’s confidence scores, students learned where to focus deeper review and which metadata fields mattered most for GBC’s users.

- Sharing with care: Before publication, metadata was reviewed for privacy and sensitivity. Person-level names were suppressed where appropriate, access was limited for sensitive materials, and decisions were documented through curator notes.

Together, these practices shifted the team’s role from manual creators to editor-curators.

“That shift—from authoring every word to reviewing and governing at scale—is the difference between backlog and discovery,” Rusty noted.

“That shift—from authoring every word to reviewing and governing at scale—is the difference between backlog and discovery.”

The results: Speed, scale, learning, and leading

The pilot demonstrated striking efficiency gains and a sustainable model—not only for the small, student-powered team but also for the broader community of collections stewards aiming to scale their work, accelerate impact, and adopt new technologies with care.

170x faster

1. Drastic time savings: The two-person team described and verified 172 images in under four hours—a roughly 170× improvement over their previous manual process. Every record received human review.

| Before vs. after snapshot (based on available data) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Metric | Before JSTOR Seeklight | After JSTOR Seeklight | Improvement |

| Images described | 250 per year | 172 in 4 hours | ~170x faster |

| Time per image | ~5 hours | <2 minutes | 99.4% time reduction |

2. Responsible description at scale: JSTOR Seeklight didn’t just speed things up—it helped GBC scale carefully, not recklessly. Built-in review workflows allowed the team to understand collections better while limiting access where appropriate.

“With the right safeguards, AI can help libraries preserve broadly, publish carefully, and scale description without scaling harm.”

“With the right safeguards, AI can help libraries preserve broadly, publish carefully, and scale description without scaling harm.”

3. A new role for student workers: Student employment shifted from data entry to critical evaluation—building AI literacy, practicing ethical judgment, and contributing to high-impact projects. The intern who co-designed the JSTOR Seeklight workflow later presented the project at the 2025 Delaware Data Science Symposium.

“Our project with JSTOR Seeklight demonstrates how AI can make the impossible routine… one that still keeps humans in the loop to ensure ethical, contextual, and accurate metadata creation.”

4. Raising institutional profile: By making its archives more discoverable, Goldey–Beacom College expanded its digital footprint beyond regional audiences. With Quartex already in place as the primary platform for publishing and enhancing its institutional collections, the library established the infrastructure needed for sustained, item-level access and stewardship. Building on this foundation, the library plans to publish selected collections alongside other open-access materials on JSTOR, further situating GBC’s archives within a broader scholarly and pedagogical ecosystem. At the same time, by modeling innovative and responsible archival workflows, the project positioned the library as a site of experimentation and institutional leadership.

A blueprint: How any institution can adapt the model

GBC’s workflow offers a clear, adaptable roadmap for institutions of any type, but especially those working under tight constraints:

- Start with a small, well-scoped collection and ideally, a previous project whose outcomes the experiment can be measured against.

- Set clear standards for contextual inputs to guide AI outputs.

- Use simple review rules to balance speed and quality when reviewing output.

- Embed training into student jobs or coursework to build both stewardship and AI literacy skills.

- Measure both speed and outcomes, tracking not just throughput, but also how much editing is required, overall impact on workflows, and how use of the tool contributes to your stewardship goals.

Proof of speed, purpose, and stewardship

In just a few hours, GBC’s small library team accomplished what once took months—describing, reviewing, and publishing nearly two hundred archival images. For Rusty, the most important outcome wasn’t the metric, it was the mindset shift.

“Seeklight helped us move faster, but it also helped us think differently about the work,” he said. “It didn’t replace careful review; it made space for it.”

Seeklight helped us move faster, but it also helped us think differently about the work. It didn’t replace careful review; it made space for it.

For institutions asking how to clear backlogs without sacrificing standards, the GBC pilot shows that stewardship can scale with care—especially when AI drafts, and people decide.

Maximize the impact of your digital collections

Join 300+ institutions partnering with JSTOR to process, manage, preserve, and share their collections with the world.

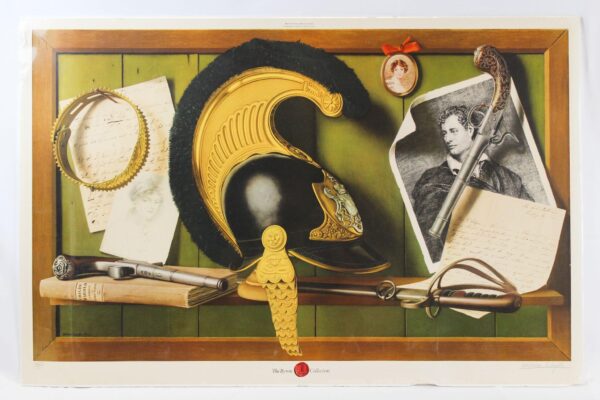

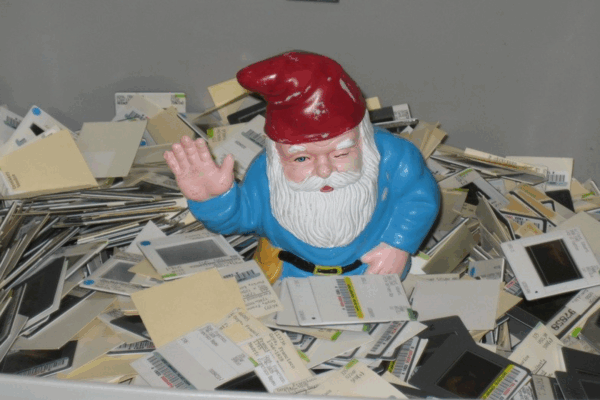

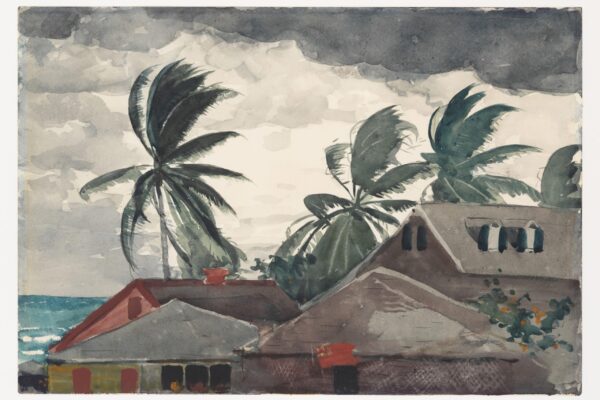

View image credits from this page

Courtesy of https://www.gbc.edu/.

Courtesy of https://libraryc.org/gbclibrary.