Antonio Canova began working on Pauline Bonaparte as Venus Victrix in 1805, the same year that Pope Pius VII appointed him Inspector General of Fine Arts and Antiquities for the Papal State. By this point, Canova’s reliance upon classical sources, idealized perfection of the forms, fluidity of line, graceful modeling, and exquisitely refined detail had solidly established his reputation as the preeminent sculptor in Europe.

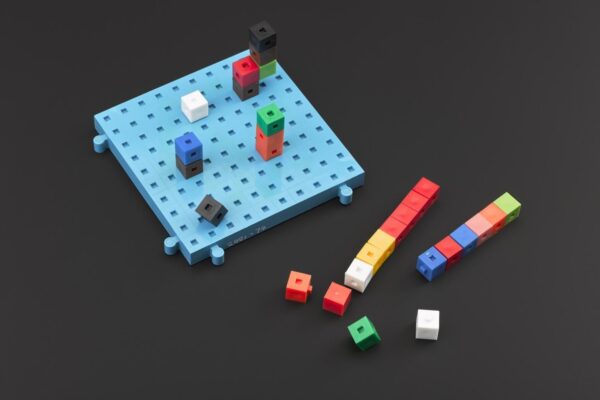

Venus Victrix is an outstanding example of the neoclassical style, which was influenced by the archeological discoveries in Pompeii and Herculaneum and considered the works of the Greeks and Romans to be the pinnacle of artistic achievements. The life-sized reclining nude exemplifies Canova’s superlative technique; the modelling of the form is both idealized and extraordinarily realistic, while Canova’s treatment of the surface of the marble captures the soft texture of skin. This luster was enhanced through a patina of wax and acqua di rota, and it was once set upon a rotating mechanism, which allowed the static viewer to observe it from all angles.

Yet the sculpture’s owner, Prince Camillo Borghese, refused to allow the sculpture to be displayed and would only show it to close acquaintances by torchlight. How did this come to happen?

Blame it on the model. Pauline Bonaparte, Napoleon’s sister, did not exactly enjoy a great reputation. While less grasping and rapacious than the rest of her family, Pauline was widely considered vain, capricious, and selfish.

After catching her in flagrante delicto in his office with one of his generals, Charles Victor Emmanuel Leclerc, Napoleon insisted upon an immediate marriage. Though Pauline seems to have been fond of her husband (who slavishly imitated her beloved brother), she was not faithful, particularly after the birth of her son Dermide. Leclerc was eventually given command of the army in Haiti, where Pauline continued to behave scandalously, allegedly with low-ranking soldiers and officers. Upon Leclerc’s death of yellow fever, Pauline was extravagant in her grief and mourned ostentatiously, at least until her return to France.

Back in Paris, Pauline indulged her material desires, spending vast sums on clothing, jewels, and entertainment. She wore her dresses outrageously sheer, and was noted for being an indifferent mother.

Eight months after the death of Leclerq, Pauline married Prince Camillo Borghese. Though Napoleon had desired the match, he was appalled at what he saw as her indecent haste. However, Borghese was one of the richest men in Italy, owning a renowned collection of diamonds and the Villa Borghese. Pauline seems to have been concerned that he would lose interest if he actually got to know her, which explained her hurry.

Not that she maintained interest in the Prince too long herself. Pauline found Roman society in general, and her husband in particular, to be staid, conventional and disapproving, and the marriage quickly soured.

Despite her capriciousness and promiscuity, Borghese was still enamored by his wife’s beauty, and he commissioned Antonio Canova to sculpt her portrait. Canova was originally commissioned to depict Pauline fully clothed as the chaste goddess Diana, however Pauline insisted on posing as nude as Venus. When asked whether she was not uncomfortable being naked before the artist, Pauline replied, “Ah, but there was a fire in the room.”

It would take many years before that fire went on public display in the Villa Borghese.

– Alexandra Moses

Source: Christopher M. S. Johns. Antonio Canova and the Politics of Patronage in Revolutionary and Napoleonic Europe. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

The image is courtesy of Scala Archives. Search the Artstor Digital Library for Pauline Bonaparte to find two portraits by Robert Lefèvre from Réunion des Musées Nationaux.