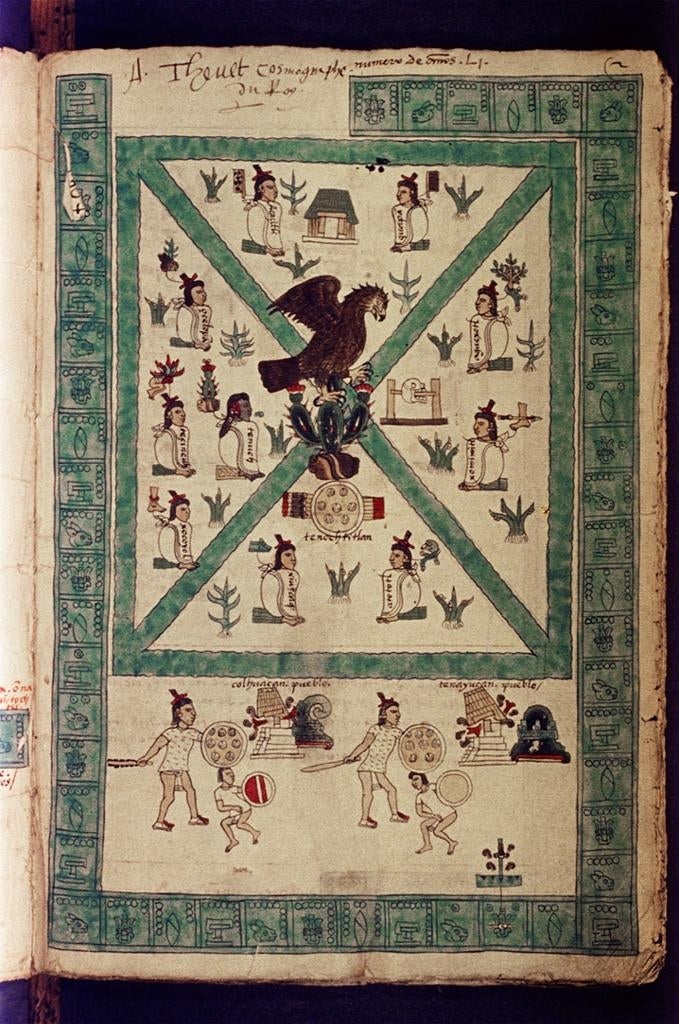

As we built our AP® Art History Teaching Resources over the last three years, we found ourselves fascinated by some of the newly required content. The art of the Colonial Americas is represented in the curriculum framework by six distinct objects. One of these is the “Codex Mendoza,” named for the first viceroy of Mexico (1535-1550), who commissioned it c. 1542 (contributed to the Artstor Digital Library by the Bodleian Library). Intended as a gift to Charles V, the manuscript never reached the monarch.

Had he seen it, King Charles V would have been treated to an exceptionally detailed education about his newly acquired territory, painted by native artists with a Spanish gloss. The frontispiece features the founding of Tenochtitlan [ten osh teet lahn], later to be known as Mexico City by the Mexica (a.k.a. Aztecs).

In the center, an eagle perches on a prickly pear cactus. According to legend, the sun deity Huitzilopochtli told the Mexica this would be the sign that revealed the place on which to build their city (other versions depict the eagle devouring a snake, which has become the coat of arms of present-day Mexico). The ten founders of the city are conceptually presented in four parts separated by blue lines representing canals. Tenoch, for whom the city was named, can be seen directly to the eagle’s left. His face is darkened like a stone, representing his name “Stone Cactus Fruit” (note the prickly pear next to his head).

A series of rectangular cartouches run around the page’s edges, each standing for a date. In the lower right corner an explosive puff of steam appears above the cartouche that represents 1521, the year the Spanish took Tenochtitlan by siege. Paralleling the Spanish conquest of the Mexica alongside the Mexica’s own conquests underscores the idea that the Europeans were the ultimate victors of this narrative. Notably, the rest of the frontispiece follows Aztec conventions: the founding myth, the pictographic nouns and verbs, and an idealized, geometric, and concentric organization.

The compelling fact about Early Colonial art is that it necessarily hybridizes the two opposing cultures involved in negotiating a new third entity, appropriately called New Spain.

– Dana Howard (with thanks to Rebecca Stone Bailey)