More than 2 million of the images in Artstor are now discoverable alongside JSTOR’s vast scholarly content, providing you with primary sources and vital critical and historical background on one platform. This blog post is one of a series demonstrating how the two resources complement each other, providing a richer, deeper research experience in all disciplines.

Decorative arts, which bridge the realms of fine art and function, often seem to highlight aristocratic tastes. These selections from The Clark’s collection, while valued for their craftsmanship and design, offer insights into the everyday lives of early Americans. These recent additions to the Artstor Digital Library also highlight a new interface in which multiple images of an object are grouped together, allowing users to access alternate views more easily.

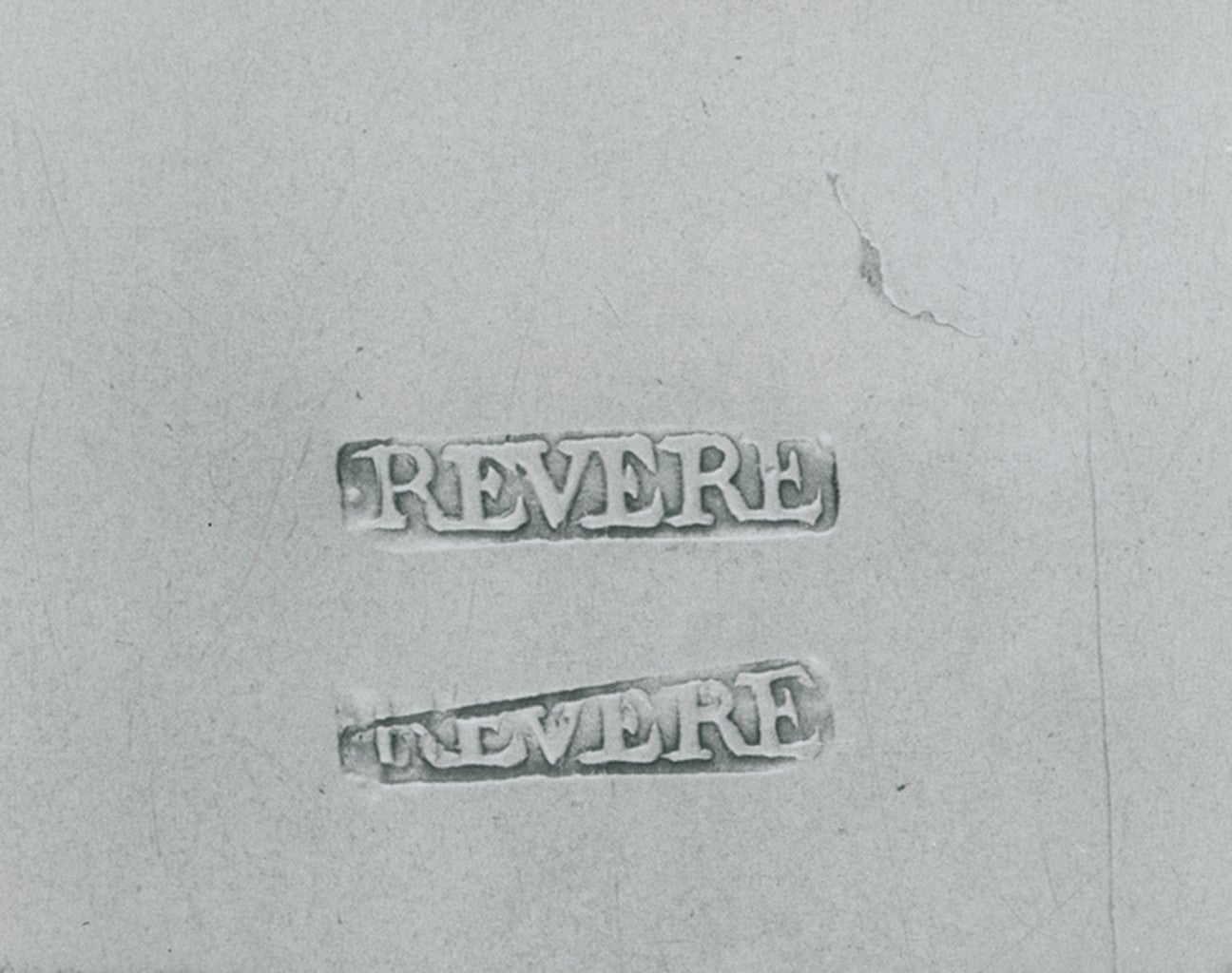

The first selections were crafted by a familiar name from the Colonial period, Paul Revere. Although he is best known for his historic ride, he prided himself as a master artisan. Views of this Neoclassical sugar bowl illustrate his advanced skills and sense of design. The tea kettle, perhaps an early example of Revere Ware (see the embossed mark in detail), was a more common piece in colonial kitchens. It reminds us of tea’s importance to the colonists – which was also borne out by the infamous protest of the British tea tax, the Boston Tea Party. Revere was in sympathy with this cause; he captured some of the passions that led up to the rebellion in a famous engraving of the Boston Massacre. (1)

Oil lamps, such as this piece from the South Boston Flint Glass Works, were essential in households before the advance of electricity. In fact, glassmaking is often cited as America’s first industry, given its origins in the Jamestown colony of Virginia. The beautifully preserved bar bottles illustrate another aspect of early American life: the prevalence of alcohol. Spirits were thought beneficial from the country’s earliest days, when the Pilgrims packed a supply of “hot waters” on the Mayflower. Settlers distilled almost everything in their gardens, from peaches to pumpkins, and drinking was the norm at social gatherings, including religious services. Even toddlers as young as one were thought to benefit from imbibing. (2)

This tankard by John Bayly, a Philadelphia silversmith, may have been kept on a shelf at the local tavern for its owner (see the initials in detail). These community houses were so popular, some historians theorize they were breeding grounds for the revolutionary fervor that arose in the 1700s. In fact, various plots against the British were said to originate in public houses, and such a large number of the country’s early leaders met regularly at Philadelphia’s City Tavern, that it was dubbed “the great gathering place for members of Congress.” (2)

Other examples of domestic life attest to the thriving trade that brought prosperity to the colonies. Nippers were used to cut pieces of sugar from large cones that often arrived from the West Indies. This child’s toy is also a teething ring made from a piece of coral that was shipped hundreds of miles. Although rare – and costly – coral was believed at the time to have protective powers for children. The elegant cream pot was created by a gold and silver smith who built his trade in the booming port of New York. Myer Myers, a distinguished Jewish artisan, is also said to be the first of his era to mark his work (see detail). (3)

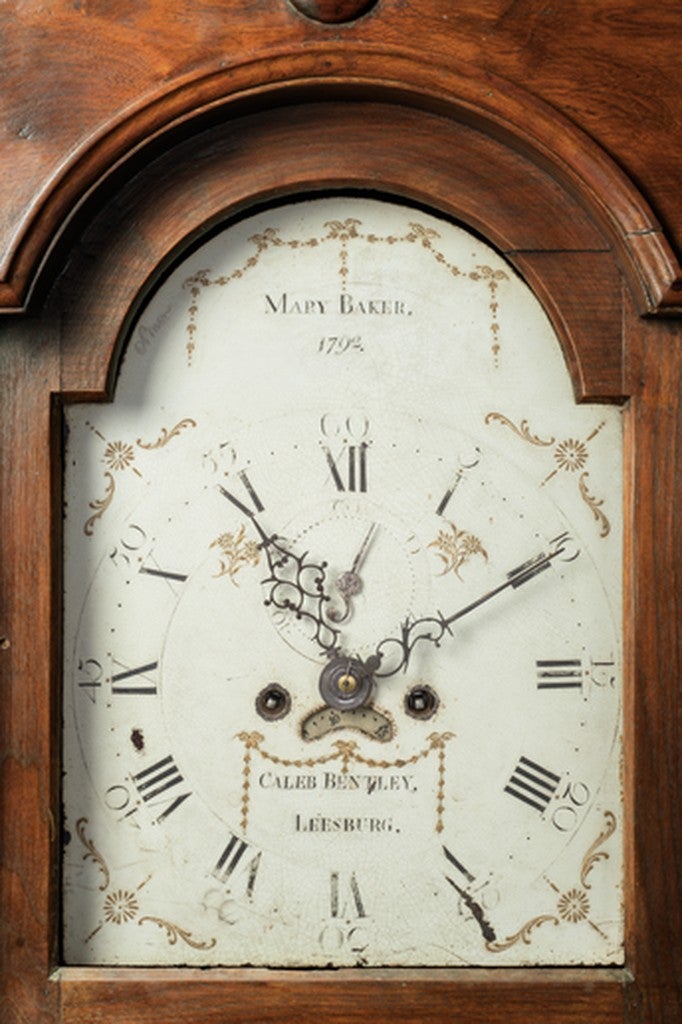

Finally, the tall clock by Caleb Bentley brings us to another chapter in American history: the War of 1812. Bentley was a prominent artisan and merchant whose social circle included James and Dolley Madison. When President Madison ran into blockades during his hasty retreat from the burning capital, he sought refuge at the Bentley’s house. Madison may have looked on just such a clock in the Bentley parlor as he contemplated his next move.

Every piece tells a story, we invite you to find others in The Clark’s collection. We also thank Laurie Glover and the staff of Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute for the inspirations.

– Lee Caron, Senior Content & Outreach Specialist

Citations

Skemp, Sheila L. “Paul Revere: Artisan Republican.” Reviews in American History, vol. 27, no. 3, 1999, pp. 368–372. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30031074.

“The First National Pastime.” Spirits of America: A Social History of Alcohol, by Eric Burns, Temple University Press, PHILADELPHIA, 2004, pp. 7–46. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt14bt147.4.

Ibid

“A New York Jewish Silversmith of the Eighteenth Century.” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, no. 28, 1922, pp. 236–238. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43059387.

You may also be interested in:

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

The curious case of collector Hearst