We was taught there’s so many different ways to build a quilt. It’s like building a house. You can start with a bedroom over there, or a den over here, and just add on until you get what you want. Ought not two quilts ever be the same. You might use exactly the same material, but you would do it different. A lot of people make quilts just for your bed, for to keep you warm. But a quilt is more. It represents safekeeping, it represents beauty, and you could say it represents family history. 1

Mensie Lee Pettway (b. 1939), on learning her craft from her mother America Irby.

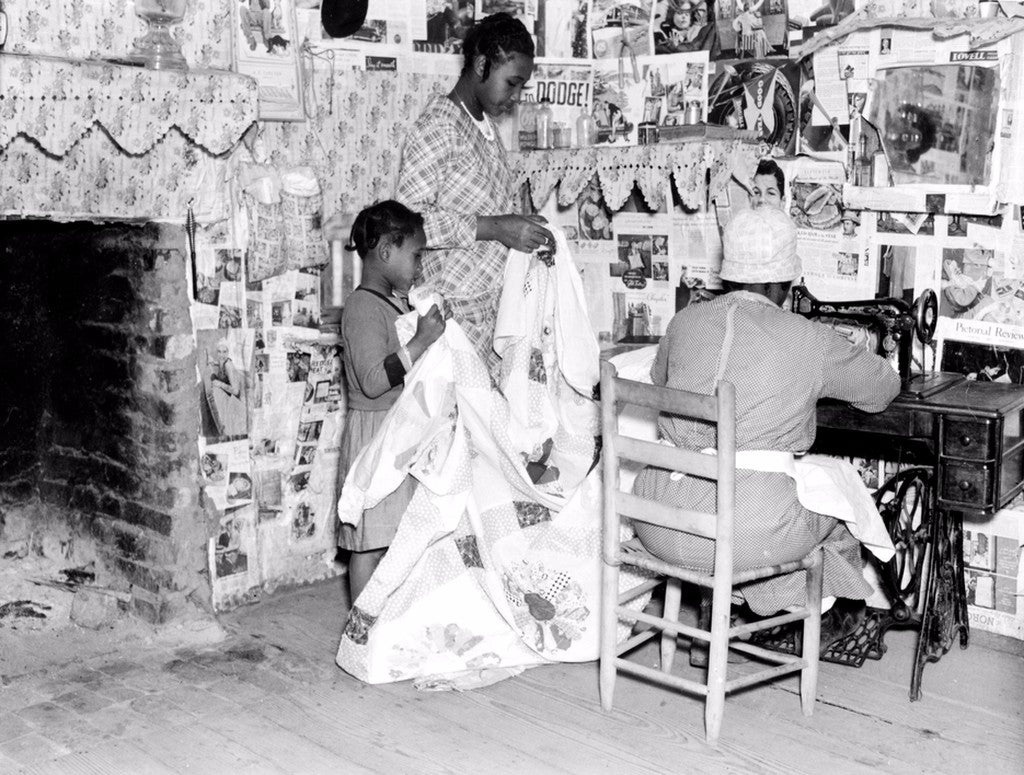

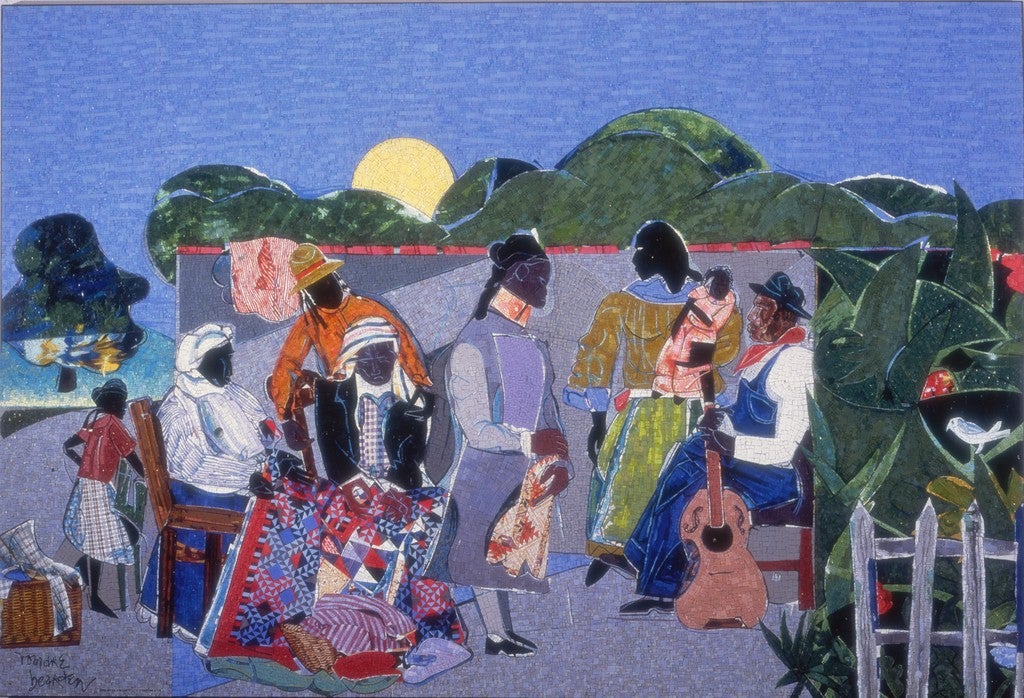

Juneteenth is an annual holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the United States, and we are celebrating with a virtual exhibition of African American quilts. June 19 observes and renews the call for freedom, justice, and equality in the African American community. From the period of slavery through emancipation and up to current times, the activities and output of quilters have embodied strength, bound the community, and bestowed beauty and warmth, echoing the spirit of the holiday. An archival photograph of two generations of the Pettway family sewing together, 1937, and the mosaic mural Quilting Time, 1986, by Romare Bearden attest to the community building/family bonding attributes of the tradition.

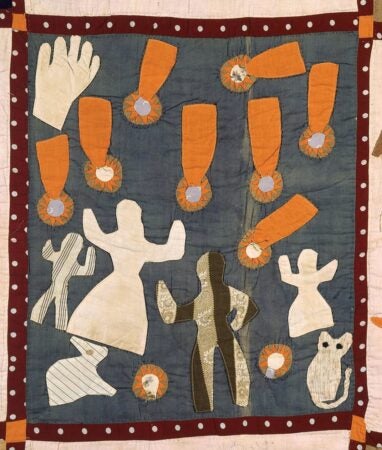

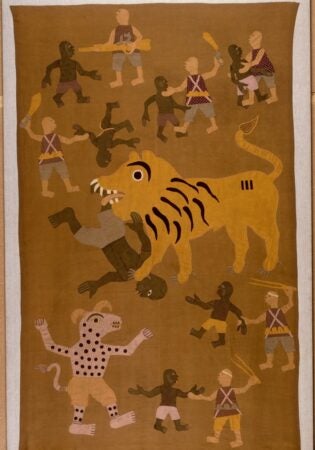

In the late nineteenth century, Harriet Powers (1837-1910) made her Pictorial Quilt, 1895-1898, one of two remarkable and celebrated surviving applique pieces by the artist. She was a farm woman from Clarke, Georgia, who had been born into slavery. The quilt weaves biblical narratives, African cosmology, and scenes of daily life. While Powers partakes of the colonial American quilting tradition, the dominant motifs of her stories, bold appliques, derive from West African textile arts as shown here in an allegorical depiction of Glélé, King of Dahomey, made by the Yémadjé family. Powers cherished her pictorial quilt and resisted an early offer from a buyer, however a financial reversal later compelled her to sell it for $5.00.

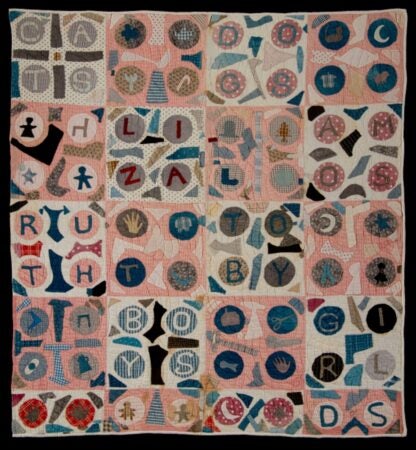

Two early 20th-century quilts further illustrate the applique technique: a vibrant, anonymous example from Baltimore or New York combines figurative and floral appliques with collages — braids, beads, buttons and shade pulls. A cross at the center shelters two angels — possibly a memorial to two girls who died in an epidemic. On the second quilt, 1901, the maker Dora Smith (active c. 1901) of DeKalb County Georgia included her initials, the names of her children, and an array of cosmic and everyday objects, including a pair of scissors — a reference to her art ? — on a relatively regular grid of red and white squares.

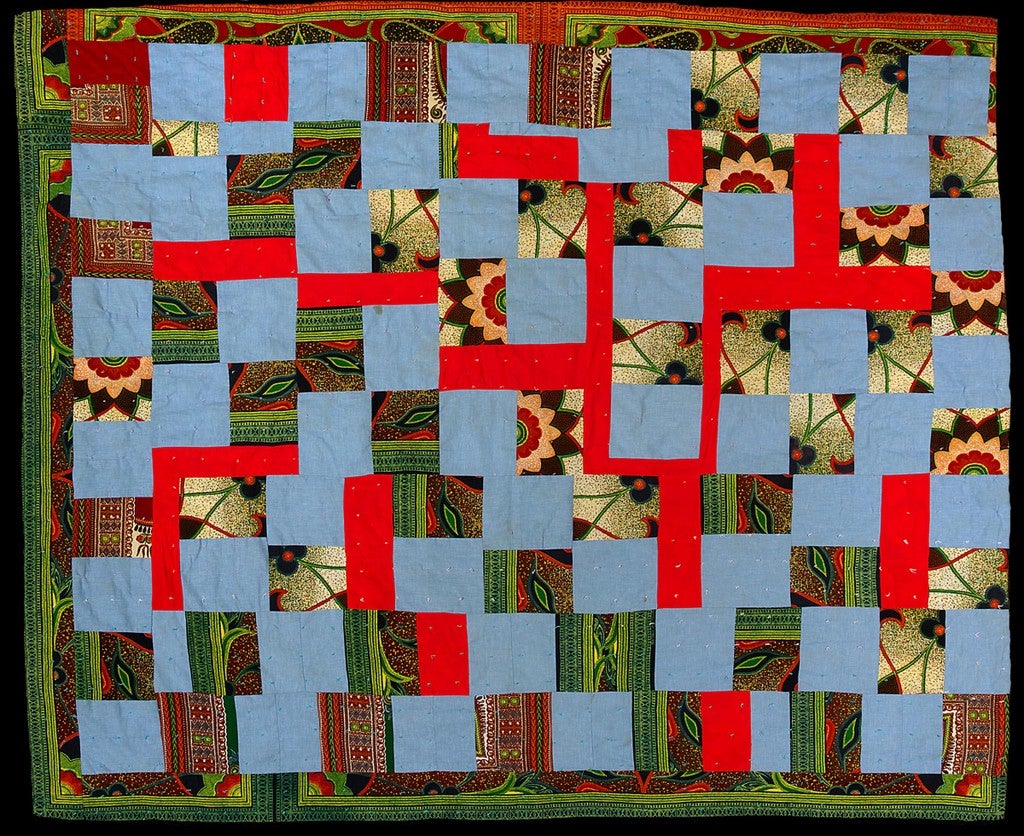

The women of Gee’s Bend, a small patch of land on a meander of the Alabama river, have achieved great fame making quilts for more than a hundred years. Many are descendants of enslaved families who worked the Pettway plantation and bear the name. The continuity of the tradition passing from generation to generation has resulted in familial successions of quilters and the handing down of particular designs. America Irby (1916-1993), described by her daughter, above, represents the quilting matriarch. Her work is illustrated here by the One Patch quilt, 1970 (shown at the top), where she used leftover scraps of dashiki cloth provided by her daughter, Mensie Lee whose recollection quoted above highlights the spontaneous “just add on until you get what you want” process that characterizes many of the improvisational designs of Gee’s Bend.

Loretta Pettway’s Log Cabin or Bricklayer Quilt, c. 1970, exemplifies her favorite pattern and the use of repurposed fabric that is a hallmark of many African American quilts. The artist (born 1942) struck a practical note in her characterization of the design: “I always did like a ‘Bricklayer.’ It made me think about what I wanted. Always did want a brick house.” 2

The use of recycled mundane fabrics is further called out in the common type of the Work-Clothes Quilt, illustrated here in an example from the 1960s made by Susana Allen Hunter (1912-2005) where patches of denim and khaki are animated by blocks of print and color. Hunter and her husband were tenant farmers in Wilcox County, Alabama and she was a prolific quilter who sewed mostly in the fall and winter when farm duties decreased. Her work is made entirely of reclaimed fabrics that bear the traces of their original function as garments — pocket shadows, seams, traces of old zippers.

Bold contrasts, asymmetry and varied textures highlight the Pieced Quilt, 1974, made by Alberta Miller (died 1999) who lived in Dallas County, Alabama, near Gee’s Bend. Miller, a mother of 20 children (and possibly more) and a caregiver made the quilt for a white girl as a high school graduation gift.

Rita Mae Pettway (born 1941) produced a version of a Housetop Quilt, a Gee’s Bend favorite, c. 1990. While the design is more structured and symmetrical than many others she created, close inspection reveals the unexpected: polka dots, Navajo-inspired patterns, and even teddy bears. Pettway described how the designs of her quilts would be revealed to her as she observed them from afar, hanging on a clothesline: “ I was looking for a design that I had put in it. A lot of times when you’re making a quilt, you can’t really see the design in it until you get a good piece away from it, or either after you finish it.” 3

– Nancy Minty, collections editor

1 America Irby (1916-1993), Souls Grown Deep Foundation

2 “Log Cabin”—Single Block “Courthouse Steps” Variation (Local Name: “Bricklayer”) Loretta Pettway, Souls Grow Deep Foundation

3 Quilt, Pieced Housetop African American, ca. 1990, Rita Mae Pettway. Colonial Williamsburg.

COLLECTIONS ON JSTOR:

- Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

- Romare Bearden Foundation

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

ARTICLES FROM JSTOR:

Cash, Floris Barnett. “Kinship and Quilting: An Examination of an African-American Tradition.” The Journal of Negro History 80, no. 1 (1995): https://www.jstor.org/stable/2717705.

Horton, Laurel. “Truth and the Quilt Researcher’s Rage: The Roles of Narrative and Belief in the Quilt Code Debate.” Western Folklore 76, no. 1 (2017): 41-68. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44790939.

MacDowell, Marsha, Justine Richardson, Mary Worrall, Amanda Sikarskie, and Steve Cohen. “Quilted Together: Material Culture Pedagogy and the Quilt Index, a Digital Repository of Thematic Collections.” Winterthur Portfolio 47, no. 2/3 (2013): 139-60. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/671567.

Sohan, Vanessa Kraemer. “”But a Quilt Is More”: Recontextualizing the Discourse(s) of the Gee’s Bend Quilts.” College English 77, no. 4 (2015): 294-316. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24240050.