This article is a part of the Inside & Connected series, which shares ideas, interviews, and projects that affect prison-based education, students, and educators.

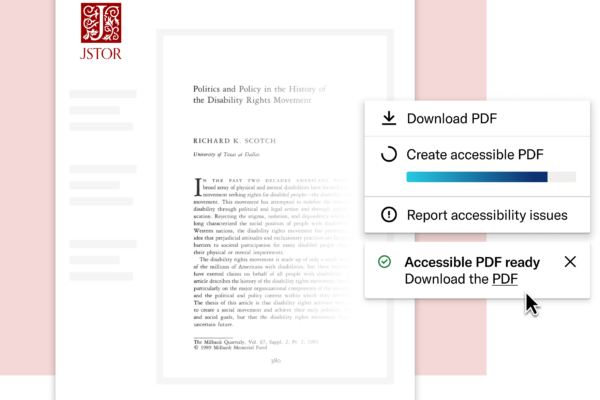

This article originally appeared on the JSTOR Labs site and has been edited for length.

In this deeply personal reflection, Ryan McCarthy of JSTOR Labs shares his experience visiting Oregon State Penitentiary (OSP) alongside Chemeketa Community College’s prison education team.

From navigating security checkpoints to helping incarcerated students conduct academic research, Ryan’s visit reveals the quiet power of access—to information, to opportunity, and to human connection. But just as important as the visit itself is the act of sharing it. Stories like this illuminate the real-world impact of educational access in carceral settings and help build understanding, empathy, and momentum for change. This is more than a tech story—it’s a story about what it means to learn, and to support these students, even in the most unlikely places.

First showcased on the JSTOR Labs site, the importance of this story moved us to include it here too as part of the Inside & Connected series, which explores the intersection of technology, education, and justice reform.

Visiting Oregon State Penitentiary (OSP) isn’t just about navigating security checkpoints and steel gates—it’s about stepping into a space where education is actively reshaping lives. On a recent visit to OSP, Ryan McCarthy, the Senior Software Engineer for JSTOR Labs, joined Chemeketa Community College’s prison education team to observe a psychology class in action. His role was to support students using JSTOR for research, but the experience offered far more than technical assistance. It was a window into the challenges, creativity, and resilience of incarcerated learners—and the educators working alongside them. What follows is a reflection from Ryan on that visit: the logistics, the learning, and the quiet moments of connection that made it unforgettable.

Walking into a prison, walking into a classroom

I’m a software engineer, and one of the things I love about my job is how quickly I get to see the results of my work. I can write code in the morning and see the results before lunch, live on the internet. But most of the code I write is for JSTOR Access in Prison, which means that while I can see the effect of my work on the website, I don’t often get to see people using the product. In fact, despite doing this work for nearly four years, until July 29th, I had never been able to see an incarcerated person using JSTOR.

Oregon State Penitentiary is a maximum security prison in Salem, OR. Chemeketa Community College’s Prison Education & Community Reentry program offers classes at OSP. I was invited by Katie Dwyer, the program’s director, and Neil Liss, a psychology professor, to visit on the day that his class was doing a research project during class time.

Prior to the visit, I met with my colleague and user experience researcher, Grace Cope, who helped me prepare. I don’t have a background in user research, and while I was mostly there to help the students use JSTOR, I was also hoping to return with insights that will help us build a stronger and more useful product. Among other things, Grace suggested focusing on what people were trying to achieve and the means they were using to pursue their goals, rather than trying to immediately solve or even identify a “problem.” It was a comfort to me to be able to approach this with a mental framework that was something other than, I am walking into a prison. The door is going to lock behind me, and I will not have a key.

Entering the facility

I arrived at the prison a bit early and waited for Katie and Neil in the lobby, a tiny room near the front door. There were a few Buddhists there for a religious service, and groups of guards coming and going. I may have arrived at shift change. I talked with one of the Buddhists about the old Space Jam website. Once Neil and Katie arrived, we waited for a guard to let us in for the next part of the process.

Getting into a prison is a great deal easier than getting out of one, but it is still a bit of a process. There’s some paperwork that has to be done in advance to get permission to visit, and a series of steps to proceed through the various security checkpoints. While we waited for the process to get underway, Katie walked me through the various stages, so that nothing would come as much of a surprise. A guard checked my driver’s license and verified that the paperwork I’d submitted a few weeks earlier had been approved. He read a brief statement about the risks of visiting a prison, which include being assaulted or taken hostage. After hearing the warnings, I took off my shoes and belt and went through the metal detector. That part was easier than getting through airport security, not least because there was no line.

After the metal detector, we walked down a long hallway. At the end, we were in sort of a trap between two big barred gates. There was a tinted window covered by bars, with a small slot in it. I had to pass my driver’s license through the slot to a man I couldn’t see. He kept the license, and in exchange he stamped my hand with invisible ink and passed a visitor badge out through the slot. At a couple of points moving through the prison, I’d have to go up to a similar tinted window and provide my name and badge number.

The education floor

The education area is on the 4th floor, up 66 steps. By the time I made it up the stairs, I was sweating a bit. Much of the prison is not air conditioned, and the stairwell was warm. The whole floor felt quite a bit like a school. There were several classrooms and a few offices. Before the class started, a couple of incarcerated workers came in to rearrange the desks to accommodate the number of students. Both in the hallways and the classrooms, the walls were adorned with inspirational quotes and artwork. Katie pointed out one bulletin board that served as a sort of “analog Facebook,” sharing odd news and quirky stories.

Some of the classrooms had portable A/C units, but the computer room didn’t yet have A/C when I visited. They’ve developed a slightly elaborate setup with four or five fans that they use to move conditioned air from a class across the hall into the computer room, which is surprisingly effective.

JSTOR access in practice

The students I met were trying to achieve a lot in a limited time, and I’d been asked to help with their JSTOR searches, so the user research part of the process was more a matter of mindset than of action. I spent most of my time giving people some tools to help them improve their search results. While I worked my way around the classroom, however, just taking a brief moment to notice what people were doing and asking them a question here and there both helped me provide them with better information and led me to a better understanding of how they were using JSTOR.

At the front of the room sat a desk with another computer and two monitors that Katie used to approve requests during the class. If you’re familiar with JSTOR, it may seem odd that students are making requests to access individual journal articles. JSTOR Access in Prison is a little different.

Navigating media review

By default, much of the content on JSTOR is searchable from the prison, but none of it is available to read or download. Departments of corrections (DOCs) typically have media review guidelines that determine what material is permissible inside carceral facilities. Ess Pokornowsky at Ithaka S+R has produced a model policy that provides an example of such guidelines. Administrators may prohibit material for any number of reasons, from descriptions of alcoholic beverages to information on computer programming, as well as violence or nudity. In a sixteenth century painting, you might well see all of them except computer programming.

In some states, content may be approved by subject without requiring permission to read individual articles. The example we often use is Aquatic Sciences. There’s very little in the discipline of Aquatic Sciences to trouble even the most stringent DOC, so it’s relatively safe to approve everything. But in states that have a lower risk tolerance for information entering a facility, every article must be reviewed individually and approved or denied. Those responsible for handling that media review tend to take their responsibilities seriously, because an error in judgment could endanger access to educational resources across the state.

More than fifteen thousand individual articles have been approved for use in Oregon prisons, across a range of disciplines.

The students and their research

Despite the obvious tension between our mission to expand access to knowledge and the unique restrictions we need to meet for prisons, student access to these articles is part of the reason I believe the tension is worth navigating. Every single article has a chance to change lives.

The students I met at OSP were working on a research project for their psychology class. One of them was looking for information on moving from conflict to peace. Another was looking into the psychology of sexual attraction. Several people were interested in a section of the textbook they’d recently read dealing with nonconformity and obedience. It’s not hard to see why those concepts would be of particular interest. Regardless of the subject matter, I know some of them found pretty interesting material on JSTOR that night, and I hope they’ll find more in the future.

There’s no telling which one might change someone’s life.

Join us on this journey

If you are part of a prison education program interested in being part of a future blog post or how to access JSTOR for your students, please reach out. To learn more about developments in prison education, resources, and access to JSTOR in jails and prison, subscribe to our newsletter The Catalyst.

JSTOR Access in Prison initiative provides a premier research database of peer-reviewed scholarly material for students in jails and prisons. Learn more at https://about.jstor.org/jstor-access-in-prison/

This series is part of our parent company ITHAKA’s mission to democratize access to knowledge and ensure that people who are incarcerated are included.