JSTOR’s interactive research tool allows users to actively engage with texts by asking questions directly within the tool. Based on user feedback, we created this guide to help you get the most out of this feature. We’ll explore how asking the right types of questions can help you quickly find relevant content, understand complex arguments, and support your research more effectively. This tool is particularly helpful for exploring densely written texts across various disciplines.

How to use the “Ask a Question” feature

The “Ask a Question” feature within JSTOR’s research tool is flexible—no need for perfectly worded questions or precise spelling! You can simply search for keywords or ask full questions to find answers based on the content within the text you’re studying.

Types of questions you can ask

Content-specific questions

These questions help you locate specific information within a document, especially in lengthy texts like books or journal articles.

Examples:

- “Is [topic] discussed?”

- “Does it mention [concept]?”

- “Does this text differentiate between [topic A] and [topic B]?”

Tip: Instead of asking “where” something is mentioned, try focusing on the topic itself. For instance, asking “Is sustainability discussed?” rather than “Where is sustainability discussed?” yields more relevant context.

Evaluation questions

Evaluation questions can provide you with an overview of the text’s central themes, arguments, and conclusions.

Examples:

- “What is the main argument?”

- “Summarize Surface key points.”

- “What are the limitations of this research?”

Why use it? This approach helps users assess the relevance of a text for their research and quickly understand complex material without reading the entire document.

Questions to avoid

Some question types do not work as effectively with the tool:

- Metadata questions: Questions like “Who is the author?” should be verified by checking the metadata on the JSTOR item page.

- Credibility or opinion-based questions: Avoid asking for opinions or assessments of trustworthiness, such as “Is this article credible?”

Applying the tool to a research workflow

Let’s say you’re researching the Gothic Revival in history. Here’s how the tool could guide you:

- Initial search: Start by searching “Gothic Revival.” Select an article and ask, “What is the Gothic Revival movement?”

- Deeper exploration: Once you understand the basics, ask, “What artists are associated with this movement?”

- Expanding research: Use “Show me related items” to find additional resources on related art movements, architecture, or influences on modern art.

This layered approach helps you build a more comprehensive understanding of your topic. To demonstrate the tool’s versatility further, here’s how it can be useful across a few different fields.

Using the tool across different disciplines

Example 1: Philosophy

Philosophy explores fundamental questions about knowledge, reality, and existence, and examines how these ideas have developed over time. In studying philosophy, you’ll critically analyze arguments from influential thinkers, interpret complex ideas, and investigate relationships between concepts and key thinkers. Here’s how the interactive research tool can deepen your philosophical research:

- Analyze arguments: Locate and explore core arguments and counterarguments in a text, such as “What is the primary argument against dualism?” or “What critiques does this text offer on Kant’s ethics?” This can help you unpack complex arguments for further criticism and analysis.

- Examine conceptual relationships: Investigate connections between key concepts, like “How does this text relate empiricism to idealism?” or “Does this discuss the relationship between language and reality?”

- Navigate the discourse: Philosophy is an ongoing conversation across history, and it can be hard to get a foothold on the concepts and thinkers in order to navigate the literature. Use the tool’s “Recommend topics” and “Show me related content” features—on a full text or a single passage—to identify key concepts for further exploration and uncover additional perspectives. This helps you trace the evolution of ideas and place them within broader philosophical debates.

Example 2: Social sciences

Social sciences are the study of people, societies, and their institutions, encompassing fields such as economics, psychology, sociology, political science, anthropology, and geography. These disciplines explore how society and individuals influence one another. From peer-reviewed journal articles to foundational social theories, the types of readings in social sciences take diverse forms.

The research tool helps you develop a concrete understanding of complex ideas—such as theoretical texts—while maintaining a critical approach. Here’s how the interactive research tool can enhance your social science studies.

- Evaluate a reading: By inputting targeted questions about a given reading, the research tool allows you to assess its strengths, weaknesses, and other key characteristics. For example, asking “What research methodology did the authors use?” or “Do the authors acknowledge the study’s limitations?” enables deeper engagement with the material and strengthens your analytical skills.

- Understanding theoretical texts: If you major in any social science discipline, you know that these fields involve complex theoretical texts. The research tool can help clarify difficult concepts. For example, you can ask, “What does Marx mean by ‘an isolated individual could no more possess property in land than he could speak’?” and receive a thorough explanation.

Deepen your understanding of different schools of thought: You can also compare and contrast various thinkers. For example, you might ask, “How is Marx’s perspective similar to or different from Weber’s conception of social inequality?” to gain insights into their theories. - Speed up your literature review: Let’s face it—you don’t need to read every article from start to finish when conducting research. The research tool is invaluable for streamlining tasks such as searching, organizing, and analyzing scholarly articles.

For instance, search results don’t always yield articles that specifically discuss the theories or concepts you’re interested in. Instead of skimming entire texts, you can ask, “How does the author apply Bourdieu’s theory of taste in this study?” to quickly determine whether an article is relevant to your work.

Even better, enhance your literature review process by pairing the research tool with Workspace, your own personal research hub available free when you sign in with your individual account. Save relevant texts to folders, organize and keep track of your research, upload your own content, and present and share all from the JSTOR platform.

Example 3: Art history

Art history research is deeply visual and contextual, often requiring scholars to analyze images, texts, and historical narratives together. Whether studying painting, sculpture, photography, or digital media, researchers must uncover how artistic movements evolved, how artists responded to social change, and how visual storytelling shaped public perception.

For example, if you’re researching 1960s American documentary photography, the JSTOR research tool can help you:

- Define the movement by asking: “What are the defining characteristics of 1960s documentary photography?” to uncover themes like social realism, activism, and raw, unscripted imagery.

- Analyze artistic influences by exploring: “How did Gordon Parks’ approach differ from that of other documentary photographers?” to compare styles, techniques, and visual storytelling methods.

- Investigate the social impact of photographic images by asking: “How did images of the Civil Rights Movement shape public opinion?” to find discussions on how photojournalism contributed to political and cultural discourse.

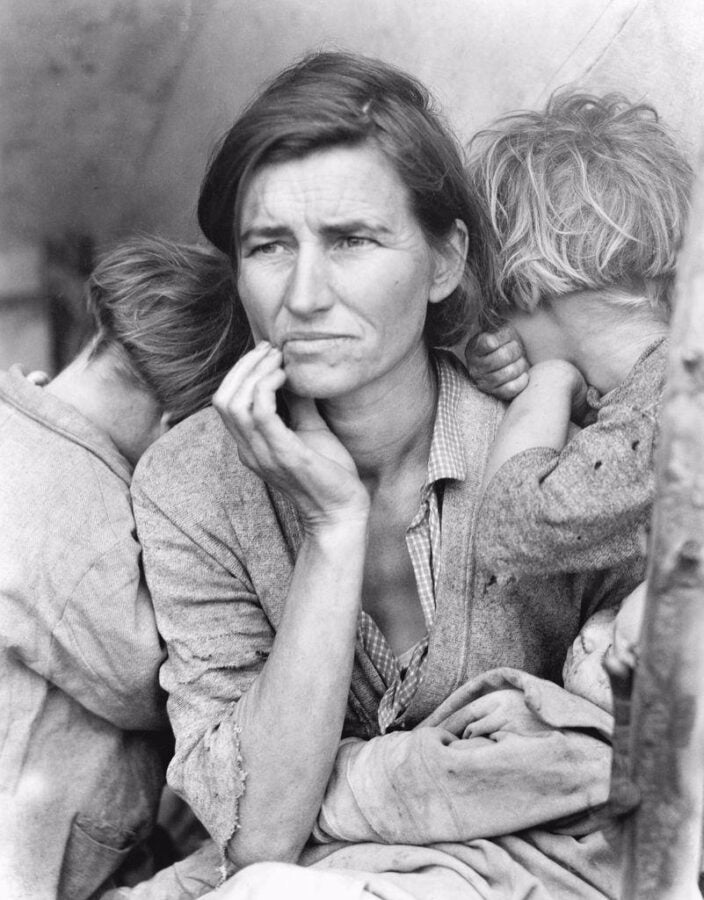

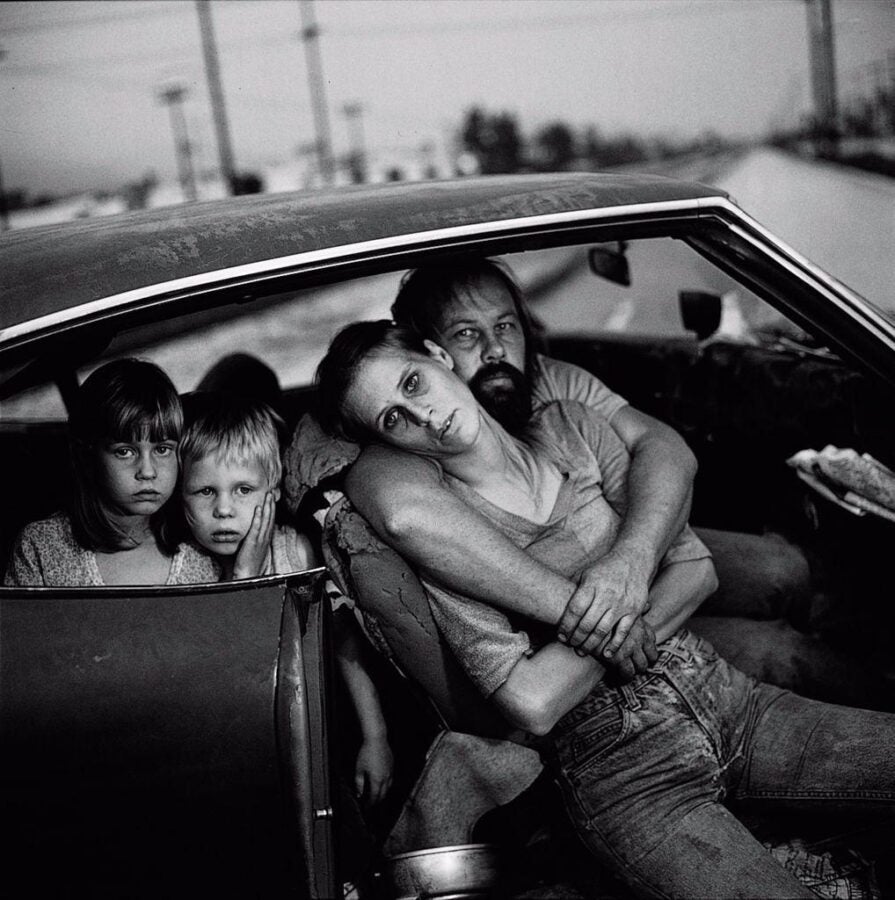

- Compare visual narratives by using the “Show me related items” tool to analyze Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936) alongside Mary Ellen Mark’s The Damm Family in Their Car (1987)—both of which document poverty but in very different eras and contexts.

Beyond textual research, JSTOR’s Workspace and image comparison tools allow you to:

- Save and annotate archival photographs, paintings, and primary sources.

- Zoom and pan to examine details in brushstrokes, composition, and framing.

- Compare multiple images side by side to analyze shifts in style, technique, and subject matter across time periods.

By integrating these tools, scholars can deepen their engagement with art history, explore artistic influences in new ways, and enhance visual literacy across disciplines.

Tips for optimizing your experience

- Ask broad questions for overviews: General questions like “What is this text about?” generate overviews, ideal for initial research stages.

- Use related features: Use “Recommend topics” and “Show me related items” to explore topics further.

- Experiment with queries: Refine your results by asking variations of questions to extract deeper insights.

Limitations of the tool

It’s important to remember the tool’s current limitations, as it is still in beta. By understanding these limitations, users can better utilize the tool within its scope and supplement their research with other JSTOR features.

- Content-only responses: The tool answers questions based solely on the document’s content, not external sources.

- Metadata limitations: It cannot retrieve author information or publication details–these should be accessed from the metadata on the item page.

- No translation: The tool currently cannot translate text or provide language support.

Enhancing your research with JSTOR’s interactive tool

The “Ask a Question” feature is designed to empower users by providing quick insights and relevant context, making it easier to tackle complex texts and foster new lines of inquiry. You can learn more about JSTOR’s interactive research tool here. If you’ve tried JSTOR’s interactive research tool, we’d love your feedback! As this tool continues to evolve, we hope it becomes a valuable resource in your research process.