This essay is part of a series exploring the enduring importance of the humanities. Stay tuned for more insights on why the humanities still matter.

I studied government and politics as an undergraduate at university during a period of unprecedented political polarization and contested truth in the United States. With information shared at ever-increasing rates via digital media and 54% of adults receiving their news from social media at least some of the time (according to Pew Research Center), there is an acute need to assess narratives for their factual accuracy, biases, and other qualities to determine their validity.

In the past decade, instances of misinformation have come to the fore, with broad acceptance of viral social media posts as fact without further attempts at verification. This is a pervasive symptom of what is popularly known as a post-truth world–that is, according to Oxford Dictionaries, a world of “circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”

This new era presents us with a unique challenge–how do we parse through information that has not been subject to fact-checking or editorial judgment? How can we pursue factual accuracy, while also recognizing the multiplicity of perspectives that shape our understanding of the world?

Studying and participating in the humanities can equip us with the tools required to navigate complex information landscapes, critically assess sources, and ultimately seek greater accuracy and understanding. By engaging with nuanced and varied concepts, we can enhance our critical thinking skills and appreciate the coexistence of multiple perspectives that shape our view of the world.

The role of critical thinking in the humanities

In my studies, I often had to dissect political rhetoric, media sources, and policy debates. Separating fact from spin required the ability to cut through conflicting information, evaluating statements not for their biases, but for the foundations of their stances. It was not enough to look at claims on their own. I had to look at where those claims came from, when and under what circumstances, to put them into context.

Definitions of critical thinking are many. At its core, critical thinking means approaching information analytically. Thinking critically is questioning the motives behind information and challenging preconceived notions about topics at hand. More than accepting information at face value, critical thinking encourages us to consider the broader narratives and implications surrounding information.

During my studies, one focus was on analyzing the 2020 presidential election in the United States with an emphasis on party polarization and media fragmentation. At the time, outlets and social media platforms were rife with conflicting narratives, all claiming to represent the truth. It was through the process of cross-referencing sources, understanding the historical context of each argument, and identifying biases that I could form a holistic scholarly perspective.

In a world where the truth is heavily disputed, where social media posts and rhetoric distort facts, critical thinking has become more crucial than ever. Without it, we risk shaping our realities on the premise of half-truths and unfaithful representations.

Studying historical texts and political philosophy has been crucial in enhancing my understanding of how narratives are crafted. Particularly, Theodore Lowi’s policy typology and Deborah Stone’s Policy Paradox have provided an important framework for discussing public policy, especially when evaluating how policy is categorized and presented. This allows me to, for instance, be aware of policies for what they are versus how they have been portrayed.

The role of human experience and emotions in the humanities

While critical thinking allows us to evaluate information for its factual accuracy, the humanities can teach us something equally important: understanding the emotional and experiential forces that drive belief and behavior. After all, what motivates people to believe narratives that may or may not be false?

Facts alone rarely carry weight enough to change the minds of entire groups. Emotions and lived experiences are what really influence our perceptions of the world. Studying politics in the late 2010s and early 2020s deepened my grasp on the emotional forces that drive political movements–fear, anger, hope. To truly grasp these dynamics, understanding the human stories behind data and headlines was of the utmost importance.

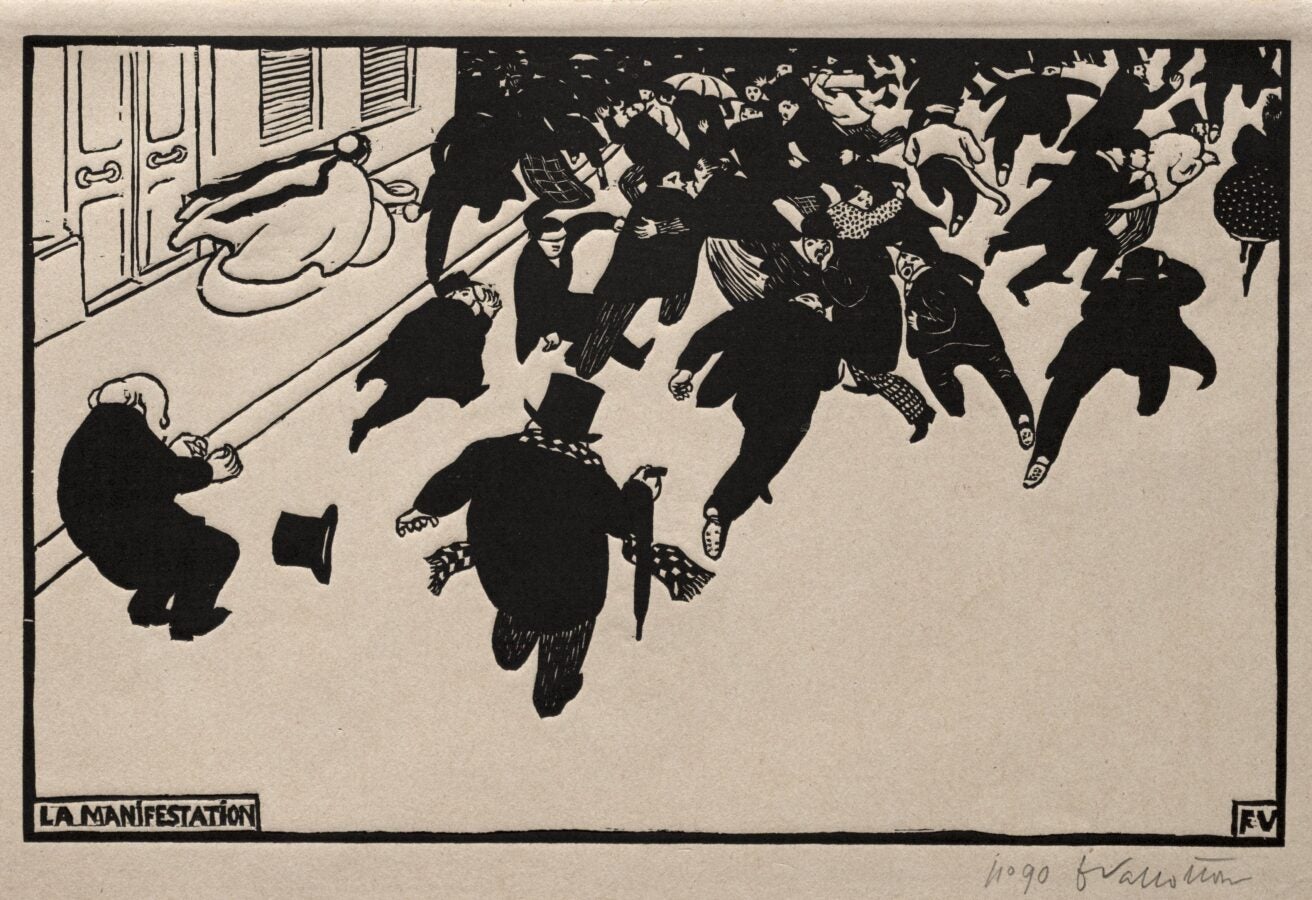

Of course, this does not only apply to politics. Mediums like literature, art, and film have a particular way of pulling at our heartstrings. From coming-of-age novels to artwork created during societal upheaval, we can experience parts of the world through the eyes of others. These mediums not only evoke emotion, but also offer the chance to better understand the human condition. Reading a novel that takes place in a new culture, looking at a work of art from a particular movement, or watching a film depicting a historical event can provide an emotional context that pure facts or statistics alone cannot.

For me, works like A Very Easy Death by Simone de Beauvior (which I discuss at greater length in a previous blog post) and Celebration by Damir Karakaš have been particularly impactful as of late. A Very Easy Death explores a complex mother-daughter relationship as it meets its end, and Celebration explores the moral conflict of a man after his involvement in one of history’s greatest atrocities. Both stories appeal to the deeply human experiences of loss, guilt, and redemption, offering readers an intimate glimpse into the emotional landscapes of their characters.

Through de Beauvoir’s candid exploration of grief and Karakaš’s portrayal of moral reckoning, I was reminded of the profound power literature holds to connect us with the inner lives of others—an essential skill in understanding both ourselves and the world around us.

These works, and others like them, demonstrate how the humanities allow us to process complex emotions and develop empathy—skills that are crucial in today’s society. In a world marked by cultural and ideological divides, empathy enables us to understand perspectives that differ from our own, fostering more meaningful communication and social cohesion. By engaging deeply with human experiences through literature, history, and the arts, we nurture the ability to navigate these divides and build more inclusive communities.

The humanities offer us tools to connect with people on a deeper level. They help us see that behind every politics, culture, and news headlines, there are real people with real experiences. In a post-truth world, understanding these human stories is just as crucial as verifying facts.

Defending the humanities: a path forward

In an era of contested truths and emotional turmoil, the humanities serve as a compass. They remind us that facts alone, while essential, are part of a greater picture. Fostering critical thinking and cultivating an understanding of the human experience through the humanities empowers us to delve deeper into information, connecting us to the histories, emotions, and perspectives that our world is composed of.

Knowing this, defending and teaching the humanities is more important than ever. With misinformation eroding trust in institutions and media, equipping future generations with critical thinking skills, openness to diverse perspectives, and empathy can help cultivate both intellectual rigor and emotional intelligence.

Advocating for the continued teaching of the humanities in classrooms, universities, and public spaces will allow us to teach thoughtful engagement with ideas for generations to come. It will help us see beyond our own experiences and hold space for the stories of others, understanding the world in all its depth and nuance.

The humanities offer us a way to live meaningfully in the world. As we face the challenges of a post-truth society, we need more than to simply analyze information. We need to build a future grounded in empathy, reason, and a shared commitment to the truth.