In 1846, dentist William T. G. Morton assembled a group of doctors in the operating theater at Massachusetts General Hospital, a sky-lit dome located on the hospital’s top floor. As the doctors watched from the dome’s stadium seating, Morton waved a sponge soaked in a mysterious substance called Letheon inches from his patient’s face. The patient quickly lost consciousness and remained completely still as a surgeon removed a tumor from his neck. Upon waking, the patient declared to his astonished audience that he had felt no pain. This surgery marked the first time the effective and safe use of anesthesia was demonstrated publicly, ending centuries of agonizing pain during surgery. It would also quickly spiral into a dramatic controversy surrounding Letheon’s discovery.

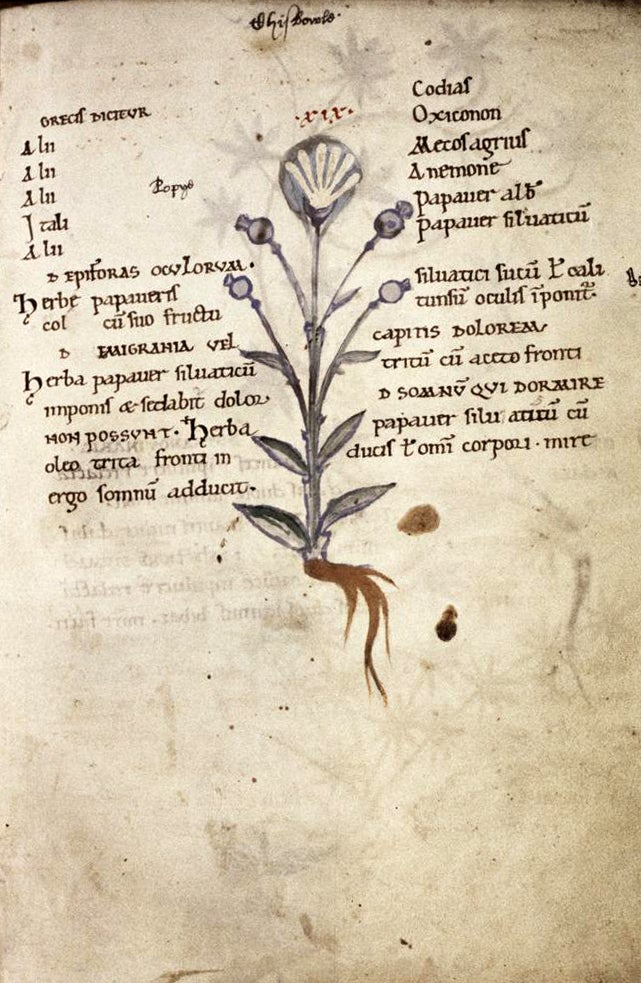

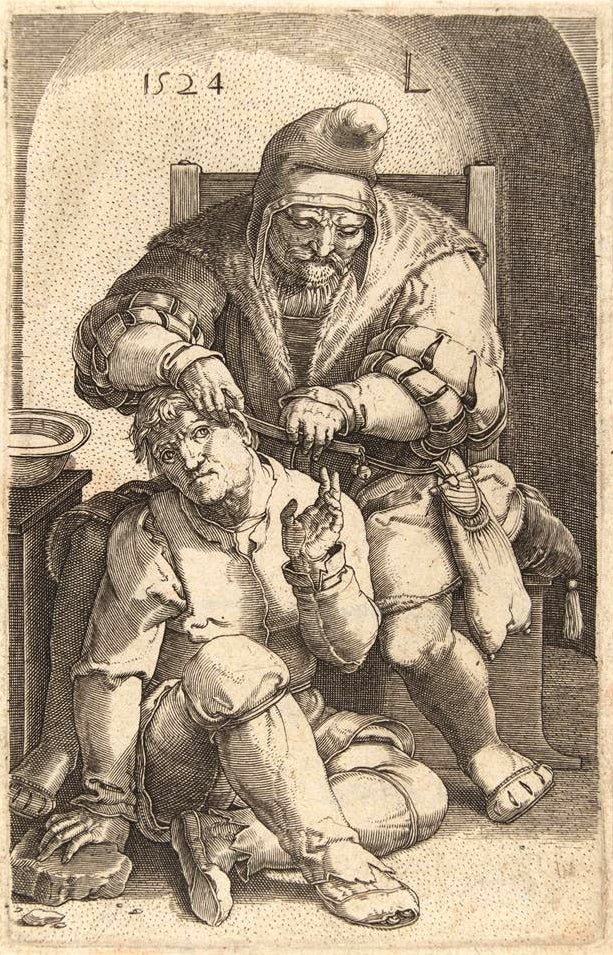

Early forms of anesthesia were dangerous and largely ineffective, and surgery was a torturous, painful experience. A cordial of mandrake root first used in Greco-Roman times is thought to have been one of the earliest forms of anesthesia. Capable of producing unconsciousness, it also caused hallucinations, asphyxiation, and high death rates. Other crude forms of anesthesia such as opium, alcohol, and a swift knock to the head with a mallet had similarly dangerous side effects, and none rendered patients fully insensible to pain. Most patients went under the knife fully conscious and able to feel each cut.

In the 1840’s a solution was found literally under doctor’s noses. At a time when the Temperance movement heavily influenced social habits, partygoers abstaining from alcohol were still looking to have a little fun. They discovered a substitute vice in ether, which produced euphoria when inhaled in small doses, and, it was soon found, stupor and complete insensitivity to pain in larger doses. Parties called “ether frolics” became a popular pastime, catching the attention of prominent chemist Charles T. Jackson of Boston. When he couldn’t fulfill Morton’s request for nitrous oxide, Jackson knew exactly what to recommend as a replacement.

After testing ether on several dental patients, Morton approached surgeons at Massachusetts General Hospital regarding its potential for use in surgery–or rather, about the promise of a new substance he claimed to have invented called Letheon. Although Morton was a dentist, he was also a businessman. He withheld Letheon’s true composition until after the spectacularly successful demonstration at Massachusetts General Hospital–and then, he patented it.

Morton, a brazen narcissist, was angered when Jackson claimed joint credit for the discovery and the two were forced to share a patent. They fought viciously over who deserved credit for the discovery, and Morton set out to cement his place in history with a blazing campaign marketing his own success with no mention of Jackson. Morton’s shameless self-promotion included a vast estate named Letheon in Wellesley, MA (funded by the abundant profits of their patent), print advertisements lauding his discovery, and even a fabricated story about his heroism administering ether to soldiers wounded on Civil War battlefields that was debunked by doctors who actually attended wounded soldiers.

As Morton and Jackson battled over their discovery, news of the historic medical advancement spread quickly. Famed Boston Daguerreotype studio Southworth & Hawes commemorated the discovery in several photographs, including an image of a reenactment of the first public demonstration of Letheon which had taken place six months earlier. Other images captured by the studio show real surgeries in the operating theater at various stages. In one image, a group of doctors including famed surgeon Joseph Warren observe as a patient receives ether from a sponge held inches from his face. Interestingly, the figure administering ether in the image is not Morton himself. Rather, an associate of Southworth & Hawes served as a stand-in. It’s not known if this choice was a matter of convenience, or was made to avoid the controversy surrounding Morton and Jackson’s discovery.

A monument in the Boston Public Garden titled “The Good Samaritan,” commonly known as the Ether Monument, sidesteps the controversy entirely. Architecture firm Ware & Van Brunt collaborated with sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward to create the monument, which depicts a doctor in medieval costume holding the limp body of a patient rendered unconscious with a cloth soaked in ether. Rather than commemorating any particular figure involved in the discovery, the monument honors the advancement itself in an inscription stating “To commemorate that the inhaling of ether causes insensibility to pain. First proved to the world at the Mass. General Hospital in Boston, October A.D. MDCCCXLVI.”

– Megan O’Hearn, Education & Outreach Manager

Images: The stunning Southworth & Hawes photograph of surgery comes to Artstor from the J. Paul Getty Museum collection; the illustrations of early forms of anesthesia come from the Bodleian Library and the Rijksmuseum collections; the photograph of Massachusetts General Hospital comes from the Ezra Stoller Archive; and the Ether Memorial from the Art on File collection.

If the top photograph startled you, we highly recommend you check out “Inside the Operating Theater: Early Surgery as Spectacle” from our friends at JSTOR Daily.