Truman Capote’s fame transcended his literary status; he was famous for being, well, famous half a century before reality television and social media stars even existed. Also a uniquely gifted writer, Capote sought fame through publicity stunts, television appearances, and his friendships with both the social and Hollywood elite of the mid-twentieth century. Capote nurtured a persona based on being entertaining, rapier-witted, and eager to spread a rumor–attributes that would later haunt him.

Born Truman Streckfus Persons on September 30, 1924, Capote was the unplanned son of teenaged parents in New Orleans, Louisiana. They divorced when he was four and sent him to live him to with relatives in Monroeville, Alabama where he befriended Nelle Harper Lee, who would later write To Kill a Mockingbird. The character Dill is supposedly based on Truman and Lee later helped Capote while working on In Cold Blood.

By the early 1960s, Capote was an established writer who had won an O. Henry Award and written two novels, Other Voices, Other Rooms and Breakfast at Tiffany’s. His public persona complemented his writings; as author Tison Pugh put it, Capote “performed his celebrity queerly, living openly as a homosexual man in nonchalant defiance of American mores.” Along the way, he had worked with, befriended and, in some cases, betrayed, various Hollywood actors, including Errol Flynn and Montgomery Clift (with whom he claimed to have sexual encounters), Marilyn Monroe, John Huston, Marlon Brando, and Elizabeth Taylor.

Capote also ingratiated himself into the elite echelons of New York society by befriending a group of society wives he later dubbed his “Swans.” This inner circle included Slim Keith (the occasional mistress of Ernest Hemingway and wife of Howard Hayward), Lee Radziwill (sister of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and future mother-in-law of Carole Radziwill, a real housewife of New York), C. Z. Guest (a fashion maven who was muse to Salvador Dali, Andy Warhol, and Diego Rivera), Gloria Guinness (married to an heir of the Guinness beer family), Marella Agnelli (Italian royalty and wife of Fiat chairman Gianni Agnelli), and his best friend, Babe Paley (style icon and wife of William S. Paley, founder of CBS).

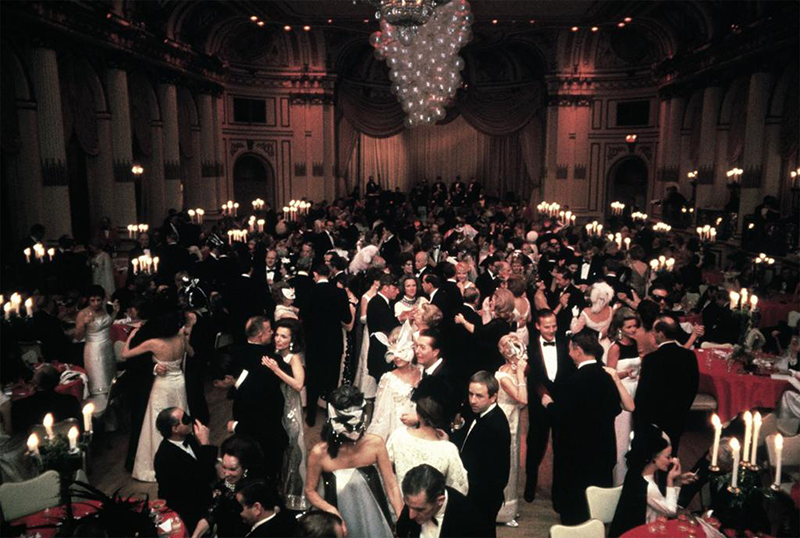

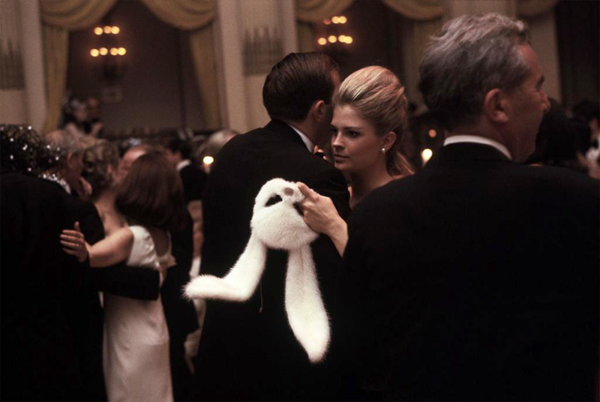

In January 1966, In Cold Blood was published. It ushered in a new type of true-crime book, which Capote called the “nonfiction novel” and is also considered his best work. It was an instant success and continues to be the second-biggest-selling true crime novel, after Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter. Later the same year, Capote chose to celebrate his success (and create yet another sensation) with a once-in-a-lifetime “Black and White Ball” at the Plaza Hotel on November 28, 1966.

Capote sought to bring disparate sectors of high society together at the Ball. Attendees included Candice Bergen, Frank Sinatra and Mia Farrow, Gloria Vanderbilt, Lynda Bird Johnson, the Maharaji of Jaipur, his Swans, and the documentary filmmaker (later of Grey Gardens fame) Albert Maysles. It was a masquerade ball, beginning at 10 p.m on a Monday night. Guests were masked and dressed only in black and white—Capote was inspired by the race scene in My Fair Lady. In the weeks before the ball, Capote had created a stir in the New York papers by being coy about the attendee list. And he extended that playfulness after the ball as well, by having the actual list of invitees published by the New York Times—much to the chagrin of those who claimed they had received invitations but, in fact, had not.

Both the Ball and the publication of In Cold Blood are considered to be the apex of both Capote’s literary and social achievements. Soon after, his alcoholism and drug use worsened and he never published another novel again. He did, however, publish in The New Yorker a thinly veiled roman à clef about his Swans in 1975 called “La Côte Basque, 1965,” where he outed their deepest secrets. Legend has it that he revealed a particularly embarrassing story about William Paley’s infidelity. Babe, his favorite “Swan” and closest friend, never spoke to him again. She died in 1978 of lung cancer. The story also supposedly caused Ann Woodward to commit suicide, as it dredged up the sordid tale of the death of her husband, William Woodward (heir the Hanover Bank fortune), in 1955. Ann, thinking there was an intruder in the house, shot her husband. It was ruled accidental but, in particular circles of society, rumors spread that she had shot him on purpose because he was planning to divorce her. Capote’s story exposed this hushed up version of Woodward’s death and Ann, who allegedly received an early copy of the magazine, killed herself by swallowing a cyanide pill.

The story ruined Capote’s reputation and his society friends iced him out thereafter. Depressed, Capote succumbed to his alcoholism and, in an interview on The Stanley Siegel Show in 1978, a visibly impaired Capote said, when discussing his future, “The obvious answer is that eventually, I’ll kill myself without meaning to.” Capote died in 1984 at age 59. The coroner’s report cited liver disease and “multiple drug intoxication” as the cause of death.

– Vicki Saxon

Sources: Pugh, Tison, Truman Capote: A Literary Life at the Movies, University of Georgia Press, 2014. Retrieved from http://jstor.org/stable/j.ctt17572th.7

You may also be interested in: The Museum of Natural History in The Catcher in the Rye