“Was this the face that launched a thousand ships?”

So asks the title character in Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus upon seeing the radiant ghost of Helen of Troy. Marlowe was not the only artist to be captivated by Helen and her fabled beauty. Indeed, for millennia, painters, sculptors, poets and playwrights have been inspired by her story.

According to Greek mythology, Helen was the daughter of Zeus and Leda, the beautiful, mortal Queen of Sparta. Owing to her half-divine origins, Helen was not born of woman, but instead hatched from an egg. She grew to be the most beautiful woman in Greece, and received suitors from far and wide.

She eventually married Menelaus, the rich King of Sparta. However, in the city of Troy, another man was fated to seek her hand. According to the Judgment of Paris, another episode in Greek mythology, a young Trojan prince named Paris was called upon to judge a contest of beauty between three goddesses: Hera, Zeus’s wife, Athena, the goddess of wisdom and war, and Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty. Each offered Paris a reward in return for choosing them, but none was more tempting than Aphrodite’s promise of the world’s most beautiful woman. Paris judged Aphrodite the winner, and went to Sparta to claim Helen, despite the fact that she was married to another. His seduction and, later, abduction of Menelaus’s bride is what mythology tells us provoked the Trojan War.

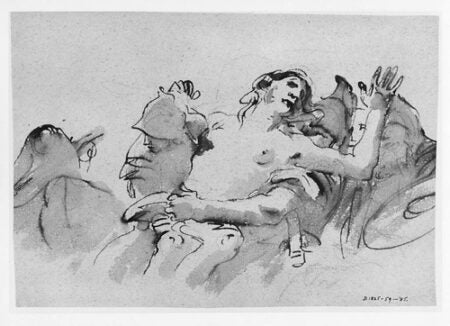

Given the subjective nature of beauty, visual representations of Helen have differed throughout the ages, changing to match artists’ preference and meet the respective era’s standards of female beauty. The plot of the story also varies between representations. In some depictions, Helen follows Paris willingly to Troy. In others, she is forcibly, violently, removed from her home.

Part of this narrative confusion stems from Greek mythology and ancient Greek literature itself, which offers many versions of Helen’s tale. In Sappho, Helen leaves her husband and daughter, Hermione, of her own volition, caught in the swell of desire’s power. The poet Alcaeus similarly acknowledges Helen’s agency and desire in leaving Menelaus but, unlike Sappho, rebukes her for it, painting her as a bad wife and harbinger of war. Homer’s representation of Helen is mixed, with the figures of The Iliad offering diverse commentary on Helen’s moral character, role in leaving Menelaus and culpability in causing the Trojan War.

These images, culled from the Artstor Digital Library, offer different visions of Helen that, taken together, show the complexity and richness of the mythological figure, and the many ways she has appeared throughout the ages.

A look at the images also forces a reflection on what we want Helen to represent in today’s world. In a compelling piece published in April in The New Republic, for example, scholar Emily Wilson reads the myth of Helen through a feminist lens, noting that it raises questions about female beauty and women’s roles in society that render the story relevant in the 21st century. As she expresses, we are still “grappling with the questions raised by the myth: whether beautiful women are always ‘bad,’ and whether they really count as people.”

How to situate or understand Helen and, more importantly, which lessons we want her story to teach remains open to debate. The artists of past generations have spoken. What new readings and interpretations will follow?

These images come to the Artstor Digital Library courtesy of the Bodleian Library, Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives, J. Paul Getty Museum, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Detroit Institute of Arts, Victoria and Albert Museum, Gernsheim Photographic Corpus of Drawings, the Illustrated Bartsch, and the Walters Art Museum.

You may also be interested in: Three classical myths to keep you awake