Our thanks to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), which contributed the Roger Brown Study Collection, over 800 images of the artist’s work, to the JSTOR Digital Library. The collection encompasses the artist’s career, from 1970 through 1997, and includes paintings, mosaics, and mixed media.

When Roger Brown arrived in Chicago in 1962, it was a heady time to be an artist. The spirit of change that transformed the sixties was already in process at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. As part of their formal training, students were exposed to unusual approaches. In one notable example, Jean Dubuffet’s talk on “Art Brut” so inspired one group of postwar artists that their grotesque works came to be known as the “Monster Roster.” Banned from the Institute’s annual exhibition, the group launched their own series of counter-shows that many see as an important precedent for Chicago’s later art movements.

During Brown’s tenure, that sense of rebellion pervaded SAIC. Some professors rejected traditional Renaissance works in favor of Surrealism or expressionism. Many forms of non-Western art were taught, including folk and primitive art, and SAIC was one of the first schools to recognize self-taught practitioners as artists in their own right. This mix of influences resulted in an explosion of creativity. Shows by The Hairy Who or the False Image featured artists with a strong representational style who came to be known as the “Chicago Imagists.” Advertising, the comics, and other popular imagery were sources for their quirky observations on modern life (as with “Mr. Cocky and Miss Petunia: Or An Allegory of Contemporary Youth”). As one critic noted, the Chicago Imagists “were unified not by a shared visual style but by common attitudes and enthusiasms.”1

There was no lack of enthusiasm. Exhibition openings were more like happenings than viewings for the “Midwest’s merry pranksters”; many of their works were as renowned for their wit as their execution. This energy propelled Chicago to national prominence by the eighties. Like many of his colleagues, Brown rejected New York art movements that dominated the art world during this period; they were thought to be too heavily defined by European ideals. This view is highlighted in Brown’s visual pun on a style closely identified with Abstract Expressionism, “Four Color Field Paintings Intersected by a Four Way Stop.”

A son of Alabama, Brown valued work that he viewed as uniquely American: artists like Grant Wood, Edward Hopper, Marsden Hartley, and Georgia O’Keeffe. Although he often explored the countryside in his work, during his years in Chicago he celebrated the bustling metropolis as a reflection of the dynamic American spirit. The city’s renowned architecture was a recurring motif. Skyscrapers teeter off-center as a metaphor for the precarious nature of urban life in “Windy City Simultaneity.” His keen eye for life on the streets, and the darker side of society, is also evident in “Mobile Homes.”

Although Brown’s work became increasingly complex, he remained committed to ensuring that it was always accessible. Like many of his fellow alum, he rejected fine art conventions in favor of a complex narrative. His combination of artistry and sophisticated commentary soon garnered a following. Despite his rejection of the Chicago Imagists label, he became known as one of the leading figures of the group it defined.

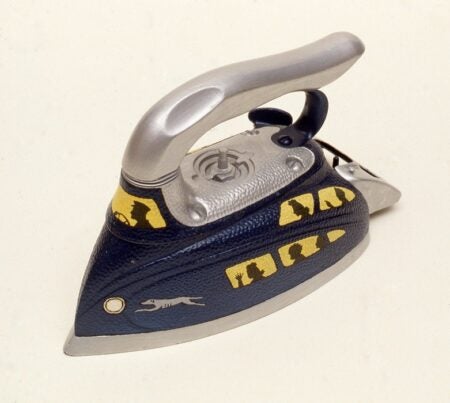

During his training, Brown developed a high regard for the meaning of objects for the visual artist. One of his professors often took classes on explorations outside of the School to hunt for “trash treasures.” Brown became an avid collector of found objects from around the world. Sometimes, as with his whimsical “Greyhound Bus Iron,” he transformed a found object. He also enjoyed playing on the tension between the paintings and objects, as in his pointed piece, “XXX Exxon.”

As Brown’s reputation grew, he was given opportunities to create public works. “Arts and Sciences of the Ancient World: The Flight of Daedalus and Icarus” soars above the downtown streets he haunted in his youth. Composed of Italian glass mosaic and stone tile mural, the installation could be seen as a tribute to the Italian primitives he admired: artists whose two-dimensional work existed before the Renaissance was dominated by rules of perspective. Some wondered if the piece, based on a myth that warns against the danger of too much pride, might have been a cautionary note given its placement in the Financial District.

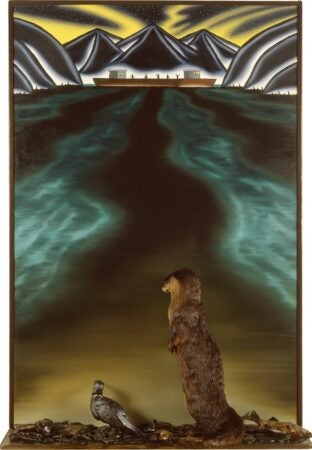

Perhaps Brown’s most enduring legacy was his endowment to SAIC: his house museum and vast archival collection, that is now known as the Roger Brown Study Collection (RBSC). In correspondence with Lisa Stone, Curator of the RBSC, he explained why he thought the building should be named the “Artists’ Museum of Chicago” and also offered an insight into his life’s work, “… I feel the things in the collection are of universal appeal to all artists and people with a sense of the spiritual and mystical nature that material things can provoke.”2, 3

Learn more in the Roger Brown Study Collection page in JSTOR.

— Lee Caron

1 McCarthy, Paula “The Chicago ‘Imagists’” Irish Arts Review (1984-1987), Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring, 1985), pp. 22-24, Irish Arts Review, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20491716.

2 “Roger Brown Study Collection: Artists’ Museum of Chicago” School of the Art Institute of Chicago. www.saic.edu/t4/academics/libraries-special-collections/roger-brown/study-collection/artists-museum/.

3 The curator describes some of the considerations for the historic preservation of an artist’s house/museum. Stone, Lisa “Playing House/Museum” The Public Historian, Vol. 37, No. 2 (May 2015), pp. 27-41. University of California Press on behalf of the National Council on Public History, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/tph.2015.37.2.27