Georgetown University’s James J. O’Donnell is contributing images of Deir Mar Musa, a monastic compound north of Damascus, to the Artstor Digital Library. Here, O’Donnell gives us a short history of the site and shares his experience of visiting.

Deir Mar Musa began life as a Byzantine watchtower, served as a medieval hermitage and modern monastery, fell into disrepair and neglect, and was then brought back to life a few years ago as a brave and venturesome monastic community and place for Christian and Muslim Syrians to meet in mutual respect. It has become a different kind of watchtower and monastery in the face of the murderous upheaval all around it.

The place is located where it is because of the intersection of geography and Roman history. The Lebanon range of mountains looms over the Mediterranean, first of a series of subsiding lines of hills at the furthest northern reaches of the rift valley that stretches from Africa to the Sea of Galilee, all running more or less southwest-northeast. Behind the Lebanon, the next range is literally called the anti-Lebanon, and between the two runs the Bekaa Valley, long the natural path of travelers going north and south from Aleppo to Damascus, two of the oldest cities in the world. When modern politics drew a line around the nation state of Lebanon, the next valley became the place for the highway spine of Syria, running from Damascus to Aleppo through Homs and Hama. Deir Mar Musa looks east atop the third line of hills and surveys the next, mostly nameless valley and the last of the lines of hills. Beyond that last line of hills, the land flattens and dries out into desert, and just there is the highway that now, as in ancient times, runs from Damascus to Palmyra to the Euphrates; the highway that was once used by Roman and Persian soldiers and merchants is now used by modern smugglers, insurgents, and tourists. The valley that Deir Mar Musa surveys was not terribly important, but it makes sense that the Romans would want to keep an eye on this “back channel,” a way from west to east that would have been favored by people looking to escape notice.

After centuries of the frontier no longer being as critical, the watchtower fell into disuse in Arab times, and the highways became more settled. “Musa,” we are then told, was an Ethiopian prince on fire with Christian zeal, whose father disowned him for his religious excesses, and so he went off as an itinerant pilgrim, settling as hermit in the abandoned watchtower, gradually acquiring a few companions, then followers, and then after his death a memorial monastic community that lasted in some form for an unusually long time.

When I visited the place in 2005, driven there by a friend who had supplied books for their library, I had no idea what the place was or what to expect. You drive north out of Damascus on the modern highway to a town called An Nabk, strikingly prosperous for a small town in nowhere. My host said that the men who lived there were many of them long-haul truck drivers and many worked in Saudi Arabia, hence the prosperity. From there we turned east off the road and drove a few miles through the semi-desert, looping through a pass in the range of hills before coming to a halt at the foot of one in a small paved parking lot. Through a stone arched gateway, we came to a flight of stairs and began climbing. The climb took 25 minutes, with one rest stop for two middle-aged climbers to catch breath; we must have ascended several hundred feet. At the top, a few stone buildings clustered, a terrace with spreading views, and a small community of men and women making a home there. Just then, workmen were finishing a separate women’s residence building a few yards from the original buildings. We were warmly welcomed, not least by the cat-in-charge prowling the terrace. The tour was predictable enough, including the quite respectable small library of books in numerous languages suitable for a monastery. There were some curiosities, like the entrance to the main building that was only about three and a half feet high. It was, they explained, a security measure from earlier times. If armed men wanted to break into your building, they would do so far less dangerously if each had to get down on his hands and knees and crawl through an opening one at a time.

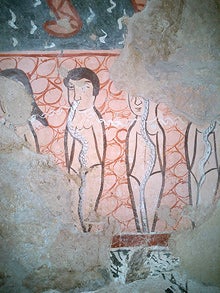

Then they took me into the chapel and my jaw dropped. “Princeton, I want my money back!” I exclaimed to myself. I took medieval art and architecture courses a lifetime ago, but I was sure that they had left this place out of the story and should not have. Modest in size (perhaps 10-15 yards in each dimension), it had walls covered in frescoes that my hosts were assuring me were eleventh century. (I now know that the correct statement should be 11th-13th, which is still pretty remarkable.) How could I have missed them? Why had Princeton cheated me?

Well, it turns out that back in the dark ages of my undergraduate education, nobody — nobody of the kind who tell things to art historians — knew these frescoes were here. The place had continued as a living monastery to a very late date, then been left essentially abandoned and untenanted in its improbable location. By good luck the roof stayed intact. It’s within my lifetime that scholars first visited the site and began to document it. In 1984, an Italian priest, Paolo dall’Oglio, began to restore the site and the community, which has lived and grown ever since.

I write this at a moment when there is only rumor to be had, but rumor says that Fr. Dall’Oglio, who disappeared in the summer of 2013 while seeking to broker good relations among warring Syrian factions, has been murdered. Words simply fail in the face of such a thought.

But in 2005 when I visited, all this awful future was unthinkable. I am no serious photographer, but I had a decent digital camera with me and I began snapping. There is happily a formal publication by a recognized scholar, Erica Cruikshank Dodd, The Frescoes of Mar Musa al-Habashi: a Study in Medieval Painting in Syria (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 2001), which I strongly recommend. A New York Times article a few years ago captured a little of the spirit of the place,

But when I found that Artstor had only a handful of images, I was happy to volunteer mine for public view. They give some idea of the remarkable cultural boundary on which this work was done and the possibilities for further study in that region. I wish I had taken more.

James J. O’Donnell is University Professor at Georgetown University. He has published widely on the history and culture of the late antique Mediterranean world and is a recognized innovator in the application of networked information technology in higher education. He has served as a Director, as Vice President for Publications, and as President of the American Philological Association; he has also served as a Councillor of the Medieval Academy of America and has been elected a Fellow of the Medieval Academy. He serves as Chair of the Board of the American Council of Learned Societies.