Sculptor Benvenuto Cellini is best remembered for two things: his bombastic autobiography, the Vita, in which he confesses to multiple murders and a spectacular jailbreak, and for his salt cellar. Yes, that’s right—a dish for salt.

Let’s start with the autobiography. Victoria C. Gardner summarizes it perfectly in The Sixteenth Century Journal:

Throughout the Vita, Cellini goes to extravagant lengths to convince the reader that he is an important and unique individual, who deserves respect and even reverence because of his artistic ability. Cellini carefully presents his contradictory character traits in a way that makes his achievements all the more impressive. Virtue and vice, for example, are paired repeatedly. He exhibits both characteristics to an extraordinary degree, simultaneously showing elevated spirituality and delight in brutality throughout the course of the autobiography… Cellini’s role as an artist is crucial to this struggle, since his creative genius is what elevates him to this greatness.

And now, what’s this about a salt cellar?

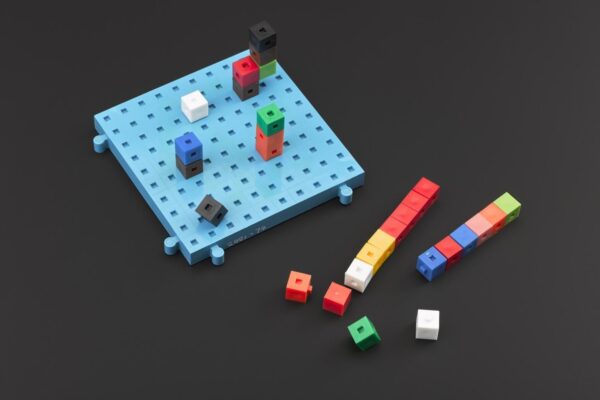

As you can see for yourself in the image above, this was no ordinary salt shaker. Measuring approximately 10 inches in height and 13 inches in width, sculpted by hand from rolled gold, resting on a base of ebony with ivory bearings to roll it around, Cellini’s salt cellar is a Mannerist masterpiece.

So what does Cellini have to say about it in the Vita?

For starters, he admits that when Cardinal Ippolito d’Este–a rabid art collector now mostly remembered for looting Emperor Hadrian’s Villa–approached him about the work, the commission included the theme for its design, but Cellini makes it clear that all the credit really belongs only to him.

According to Cellini, the Cardinal’s companions offered their suggestions for the salt cellar’s subject, which he summarily dismissed. “The Cardinal, who was a very kindly listener, showed extreme satisfaction with the designs which these two able men of letters had described in words,” he writes. “Then I turned to the two scholars and said: You have spoken, I will do.”

This is what Cellini comes up with: the gods of earth and sea, their legs intertwined “suggesting those lengthier branches of the sea which run up into the continents.” A small boat for the salt floats next to the sea god, while a temple for peppercorns is placed next to the earth goddess. Additional figures on the base represent winds and the times of day.

Notably, he doesn’t name the main figures—they would only later be identified as Neptune and Tellus. As Charles Hope explains in his book Patronage in the Renaissance, Cellini was primarily interested in the composition, and the appropriate subject matter came later.

Cellini tells us that when he presented the wax model to the Cardinal his companions butted in again. “This is a piece which it will take the lives of ten men to finish,” an adviser to the Cardinal exclaims when they are presented with the model. “Do not expect, most reverend monsignor, if you order it, to get it in your lifetime.” The Cardinal agreed and declined the piece.

The real problem might have been its cost, though, because the Cardinal took Cellini with him to present the model to Francis I, King of France.

Francis’ reaction was more to Cellini’s liking. He writes that upon seeing the model, the King cried out in astonishment: “This is a hundred times more divine a thing that I had ever dreamed of. What a miracle of a man! He ought never to stop working.” Without hesitation he then asked for the salt cellar to be executed in gold.

Cellini then changes gears and jumps into an adventure story in which he single-handedly fends off four armed bandits as he walked home with a basket laden with the gold that he received from the King’s treasurer. “My skill in using the sword made them think I was a soldier rather than a fellow of some other calling,” he writes.

When the Saliera was finally made and presented to Francis, Cellini claims the King “uttered a loud outcry of astonishment, and could not satiate his eyes with gazing at it.”

We should probably take the artist’s account of the King’s reaction with, ahem, a grain of salt. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to Cellini that there might have been other reasons for Francis’s enthusiasm. For example, Alana O’Brien suggests in The Sixteenth Century Journal that the King’s interest was due to “its message in relation to Francis I’s political and economic interests in salt production and the pepper and spice trades,” not just the object’s beauty.

But this is not too surprising. To quote Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy in Renaissance News, “even though many other actors figure in the melodrama of Cellini’s life and he comes into contact with princes, prelates, great ladies, humanists, policemen, ostlers and brigands, he sees everything in so personal a way that he is blind to many of the facets of Cinquecento life.”

You may also be interested in: