To celebrate Artstor’s collaboration with the RISD Museum, our friends at the museum graciously created a lightning-tour of their encyclopedic collection in the Digital Library through twenty notable objects. Part one focuses on decorative and utilitarian artifacts, and part two on artworks.

Aphrodite

This bronze figure of Aphrodite, now green from oxidation, once would have been a warm brown. To heighten a sense of naturalism, the eyes and hair ribbon were inlaid with silver and the lips with copper. In the 4th century BCE, the first nude image of Aphrodite was sculpted, breaking a long tradition of depicting Greek goddesses clothed. It was fitting, however, that the goddess of love and beauty was the first to be portrayed in this new way. The motif became so popular that hundreds of such images of Aphrodite survive from ancient Greece and Rome, where they adorned homes, gardens, and sanctuaries. Exceedingly rare today, bronze examples like this one must have been prized possessions of wealthy patrons.

Buddha Mahavairocana (Dainichi Nyorai)

Nearly 10 feet tall, this late 12th-century wooden Buddha Mahavairocana is the largest seated Japanese figural sculpture in the United States. A very large image of Dainichi Nyorai (the supreme Buddha of Mahayana Buddhism as taught by the Shingon sect), it represents the transcendent Buddha from whom all other buddhas and all aspects of the universe emanate. The sculpture shows him as an Indian prince in a pose similar to traditional painted depictions, in which he sat at the center of a mandala (cosmic diagram) surrounded by other buddhas and attendants. This meditating Dainichi was the focus of worship in a temple hall.

Joachim Antonisz Wtewael, The Marriage of Peleus and Thetis

This masterpiece of late Dutch Mannerist style casts a classical wedding celebration as an exuberant outdoor festival. A dense population of mythological guests is gathered for the fabled marriage of Peleus and Thetis. Served by Hermes at center, the couple seems a mere pretext for the action. The revelers’ exaggerated muscularity is heightened by flesh tones of pink, white, and brown, which distinguish male and female Olympians from satyrs and river gods. As Apollo sings the deeds of the bride and bridegroom’s yet-unborn son Achilles, Eris (Discord) tosses a golden apple into the crowd. Inscribed “for the fairest,” her fateful missile will trigger events leading to the Trojan War.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight

In this emotional Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Rembrandt portrayed the physical act of lowering Christ’s body. The diagonal of the descent is intersected by the horizontal of Christ’s limp form, mirrored in the white shroud lovingly laid out below by Joseph of Arimathea. Below Christ’s head, the artist depicted a single, well-lit hand reaching up from the darkness as if in the hope of salvation. Rembrandt was among the first to explore extensively the possibilities of etching as an expressive medium. For Christ’s face, he scratched directly into the plate (drypoint), thereby creating an eloquent shadow of death. The heavily worked background contrasts with the sketchiness of the foreground and demonstrates Rembrandt’s characteristic use of extreme darks and lights in the service of spiritual pathos.

Katsushika Hokusai, Hawk and Cherry Blossoms (Kaido ni taka)

Among the highlights of the RISD Museum’s Asian Art collection is a peerless group of more than 700 19th-century Japanese prints collected by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (1874-1948), a daughter of Rhode Island senator Nelson W. Aldrich and the wife of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. The collection includes many prints by renowned artists Hokusai and Hiroshige, among others, and is known for its bird and flower prints—one of the finest such groups of images in the world.

J. M. W. Turner, Dazio Grande

Dazio Grande is from a group of “sample studies” that J.M.W. Turner made in 1842 and 1843 in Switzerland while en route to Italy to obtain commissions for a group fully worked watercolors. It was originally purchased shortly after the artist’s death by the renowned art critic John Ruskin, who recognized Turner’s late works as the best examples through which to understand the artist.

Édouard Manet, Le Repos (Repose)

Le Repos depicts the artist Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) resting on a plum velvet sofa in Manet’s studio. Her white summer dress billows to one side, a fan rests in her hand, and above her head the animated subject of a Japanese woodblock print contrasts with her reverie. Viewers at the 1873 Paris Salon found Morisot’s casual pose to be in defiance of good taste and were uneasy with the elements of Manet’s radical style: broad, tactile paint-handling, pictorial compression, and the dominant contrast of light and dark tones. Manet called this painting a study, not a portrait, defining his concern for the visual existence of the figure over the revelation of personality. Owned first by prominent French collectors, it was purchased by George Vanderbilt in 1898, becoming one of the first paintings by Manet to enter an American collection.

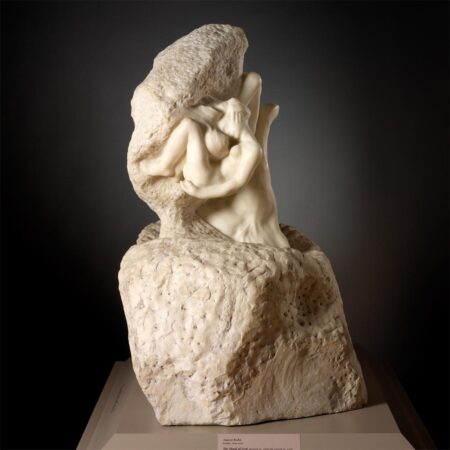

Auguste Rodin, The Hand of God

Rodin’s The Hand of God has been viewed not only as a metaphorical representation of the creation of man, but also as a commentary on the sculptor’s role as creator. The emblematic hand that emerges from a block of roughly hewn marble represents the Divine Creator forming the bodies of Adam and Eve interlocked in a primal embrace. In contrast to the figures’ slender, attenuated limbs, the sinewy hand was perceived by critics as that of a working man. Together, the well-defined hand and the ephemeral figures bridge Rodin’s interests in both realist and symbolist art. One of three known marble versions of The Hand of God, RISD’s sculpture was purchased directly from Rodin by Samuel P. Colt (1852-1921) of Rhode Island. The Museum acquired it after Colt’s death.

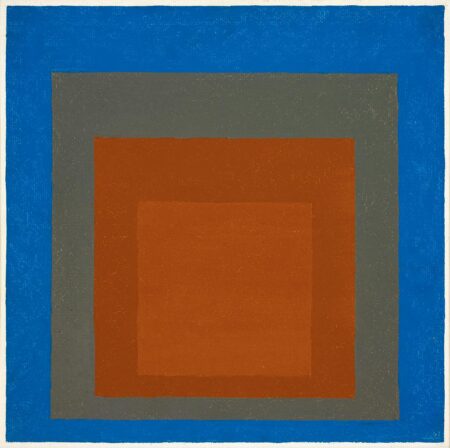

Josef Albers, Study for Homage to the Square: Concentric and Excentric

Josef Albers linked the European avant-garde with the American. A student of the Bauhaus in Germany (1920-1925), he also taught there (1925-1933). When the Bauhaus was closed in 1933, he came to the U.S. and began teaching at Black Mountain College and later at Yale University. He influenced a generation of American artists who went on to develop Color Field painting, Minimalism, and Op art. The Museum’s paintings are from his series of experiments with the perceptual effects of color juxtapositions and sequences. The orange squares of Excentric radiate and expand against the blue outer square, while the cooler colors of Concentric draw the eye inward toward the grey center, which seems to recede.

Agnes Martin, Untitled

In New York during the late 1950s, Agnes Martin began to redefine her abstract style. She moved away from large canvases of airy and subtle geometric forms toward what she considered the pinnacle of her mature work, compositions characterized by fine grids. Untitled marks a transition between these two modes. In this small painting, the variation in the density of the lines enlivens the grid. The presence of Martin’s hand is more conspicuous here than in her later works, where her lines were more uniform and less gestural. Martin remained committed to exploring the square grid, which she valued for its complete abstraction. Although her paintings are associated with simplified Minimalist forms, they are personal and spiritual in feeling.

Dan Flavin, Untitled

A key figure in the Minimalist art movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Dan Flavin worked exclusively with off-the-shelf fluorescent light tubes to create sculptures that use light, color, and simple geometric configurations to explore the visual and physical experiences of perception. Designed to be installed horizontally across the corner of a room, the fluorescent tubes of this untitled work cast a haloed diamond of red and blue light that activates the surrounding gallery space.

Go to part one of the tour.