To celebrate Artstor’s collaboration with the RISD Museum, our friends at the museum graciously created a lightning-tour of their encyclopedic collection in the Digital Library through twenty notable objects. Part one focuses on decorative and utilitarian artifacts, and part two on artworks.

Paint Box

Only a handful of paint boxes survive from ancient Egypt, and this one is particularly unique in being made of ceramic and bearing a sliding lid with a grip whimsically decorated with a genet, an animal related to the mongoose.

The stylized papyrus thickets represent the genet’s habitat of tall grasses and shrubs. Featuring a hollow well for water and brush storage, the box contains seven pigment cakes of yellow ochre, Egyptian blue (a synthetic pigment composed of silica, copper, and calcium), calcium carbonate (white), hematite (dark red), hematite mixed with calcium carbonate (lighter red), and two charcoal blacks. Painters used these same pigments to decorate statuary and the walls of temples and tombs.

Nō theater costume (nuihaku) and Man’s Court Robe

At the heart of the RISD Museum’s Costume and Textiles Collection are the many hundreds of spectacular textiles collected by Lucy Truman Aldrich (1869-1955)—affectionately known as “Miss Lucy”— the eldest daughter of Rhode Island senator Nelson Aldrich and the sister of philanthropist Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. Miss Lucy was an enthusiastic traveler and had a lifelong appreciation for the finest examples of textile artisanry. Her brilliant collecting career spanned three decades, repeat visits to East Asia, and forays to India, Indonesia, and Egypt. The many hundreds of spectacular textiles she gave to the RISD Museum form the nucleus of the Museum’s renowned Asian textile collections. Two of the most significant groupings of Nō theater robes and Buddhist monks’ mantles outside of Japan are included in these holdings, as are exemplars of Chinese, Indian, Thai, Indonesian, Persian, and Ottoman court and religious textile arts.

Palanquin (norimono) with Tokugawa and Ichijo Crests

The Edo-period palanquin, designed to transport a bride of high social standing to the groom’s residence on their wedding day, is one of only a few in the United States—and perhaps the first to enter the country.

The exterior is constructed in wood and embellished with black lacquer, gold paint, and metal fittings. Two repeated crests serve as decoration and signify that the groom descended from Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), the first military ruler, or shogun, of the Edo Period. The compact interior is embellished with an armrest and scenes from The Tale of Genji, an 11th-century masterpiece of Japanese literature about court life, written by a noblewoman. On the back wall is a celebratory depiction of a pine tree, crane, tortoise, and bamboo, all of which are auspicious symbols related to Hōraisan, the island of immortality. The wisteria crest of the Ichijō family, of which the bride was a member, appears on the coffered ceiling, alternating with the three-lobed crest of the Tokugawa family.

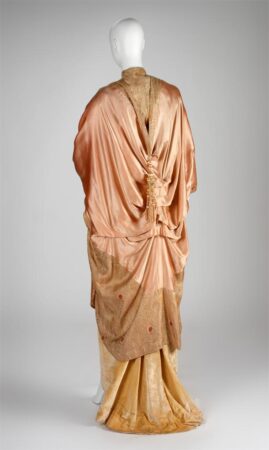

Coat

In 1874 Liberty opened its doors in London as a decorative wares emporium specializing in designs based on Japanese art and Britain’s Aesthetic movement. Like the members of the Aesthetic movement, Liberty was interested in making women’s dress more comfortable, practical, and less restrictive than late 19th-century ladies’ attire. This coat exemplifies Liberty style. The peacock-feather fabric, associated with Liberty to this day, is based on an 1877 design by Arthur Silver. The coat’s cocoon shape points to the vogue for orientalism in Europe that followed the arrival at Paris of the Ballet Russes in 1911.

Lady’s Writing Table and Chair

Commanding as much attention now as when the set debuted at the 1904 World’s Fair, the Lady’s Writing Table and Chair is a masterpiece of inlay marquetry that testifies to the technological sophistication and artistic abundance found at Victorian-era world expositions.

Gorham Manufacturing Company’s writing table and chair were conceived as showstoppers in a crowd of stunning objects made by Gorham’s competitors, most notably Tiffany and Company. More than 10,000 hours of labor, 75 pounds of silver, and a panoply of exotic materials make up this unique set, which deftly melds sinuous European Art Nouveau floral and figural motifs, 18th-century French Rococo forms, and traditional Hispano-Moresque designs. Intricately wrought symbolism—seen in the daytime poppies and the night owl below the mirror and the decoration of the legs, each representing one of the four seasons, with female masks surrounded by lilies, roses, chrysanthemums, and pine cones—attest to the complexity of Gorham’s design, which brought the Providence-based company the Grand Prize in silversmithing at the 1904 World’s Fair.

Desk and Bookcase

This lustrous mahogany desk and bookcase represents a pinnacle of achievement for American cabinetmakers. One of nine known examples, this block-front desk and bookcase with six carved shells is associated with the Goddard/Townsend family of cabinetmakers in Newport. The desk exemplifies their superb craftsmanship in the delicate dovetailed construction of the drawers. Their mastery of proportions is evident in the piece’s well-balanced broken-scroll pediment, alternating convex and concave surfaces, and integrated flame finials. In a Rhode Island house of the period, the desk and bookcase was the most expensive piece of case furniture. A combination office, safe, and library, it offered space for account books and writing materials, a flat surface for writing, and small lockable drawers for securing money or jewelry.

Zaha Hadid, Tea and Coffee Service

In the 1990s, the Italian design company Sawaya & Moroni produced a range of highly innovative silver tableware designed by leading international designers and architects, and commissioned this silver tea and coffee service from Zaha Hadid, one of the most innovative architects of her generation. The strongly architectural design for this service hints at Hadid’s deconstructivist work and reflects her belief that contemporary architects and designers “have to take on the task of investigating the modernity.”

Go to part two of the tour.