Representations of grief allow us to see the multiplicity of ways to mourn.

In November 2022, I founded a project at the intersection of art, grief, and archives called Postal Service for the Dead. It’s an ongoing, collective project that involves asking people to send letters to anyone in their life who has died.

Birthdays, death days, anniversaries, holidays, or seemingly random days can all spark grief. Writing letters to those who have died has always been a powerful tool, but we felt something was missing: the physicality of stamping and mailing it out.

Some participants of Postal Service for the Dead have shared tidings of happy holidays in a Christmas card or some have inscribed “Wish you were here” on postcards from their travels. What I have learned from this project is that grief is expansive and present throughout all of life. Representing the variety of ways grief takes shape is important to dismantle our preconceived ideas of how to grieve “correctly”.

What does grief look like?

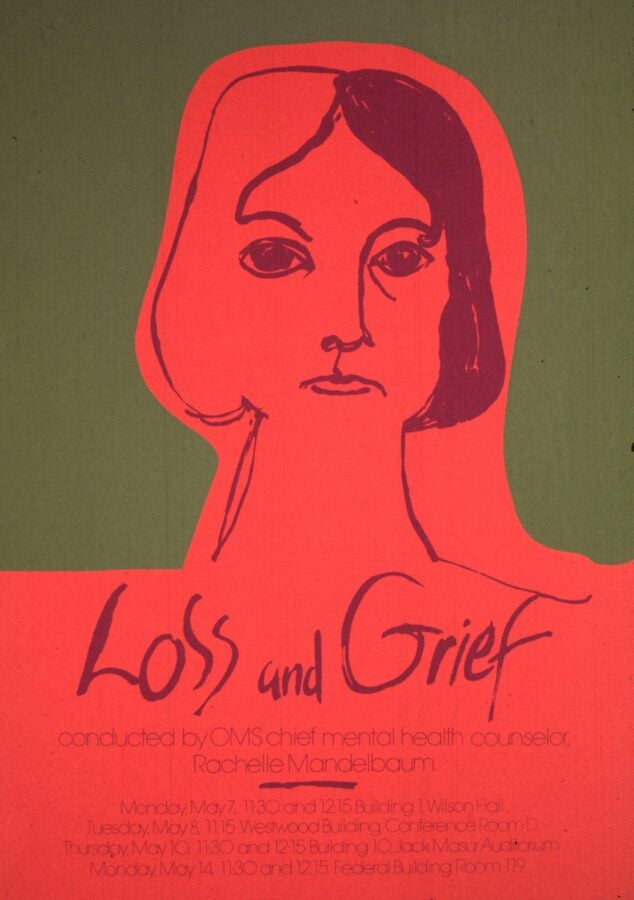

In a poster titled “Loss and grief”, which you can find in the collection Open: Images from the History of Medicine (National Library of Medicine), a line drawing of a woman’s head is sketched onto bright red paper contrasting with the dark green background behind her. With a slightly turned down mouth, one might interpret her expression as sad. And in the darkness of her eyes, we might see tiredness. Alternatively, she might be contemplative or nostalgic–thinking of whoever she just lost. One half of her head is in shadow while the other is in light; a reminder that often in grief we feel moments of joy alongside moments of heaviness.

A gouache painting by Reginald Cleaver, depicts young to old relatives decorating graves with flowers, photos, wreaths, candles, and framed portraits. An elderly woman carrying a large basket of decorations passes by a young man and child decorating a grave. The slight smile on her face indicates this is a peaceful, even joyful moment, not one of sadness. Rendered in shades of grey, the scene initially feels like one of sorrow. But upon closer inspection we can also interpret it as a gentle and respectful celebration of life.

What do we do with grief?

For many, the death of someone in our life can feel like our whole life is uprooted or that our reality has shifted. Using art and connecting with our community is a powerful tool to process death and honor our grief—especially for traumatic and disenfranchised deaths.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt, a project to remember and celebrate the stories and lives of those lost to HIV/AIDS, is an incredible testament to over 110,000 individuals honored through the art of quilting. Found in Reveal Digital’s HIV, AIDS & the Arts Collection are examples of panels being crafted with care, giant quilts on display, and the living—the grieving—who come to reflect.

In an image dated 1992, two kneeling women embrace one another while they read a panel honoring Stephen Clark. Stitched into the panel are lyrics from “Wind Beneath My Wings”, a pug, and a pair of scissors as iconography that keeps Stephen’s spirit alive.

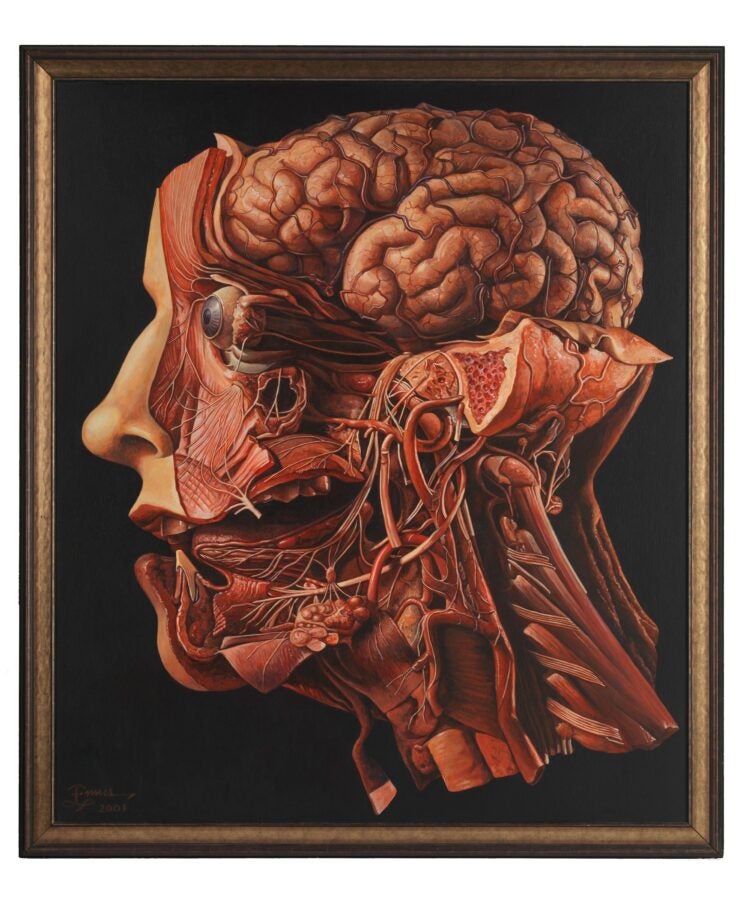

Creativity encourages the process grief in ways that are unique to each individual. Take for example, Richard Ennis’ In Memoriam, which he painted to memorialize a friend who died of cancer. Some find comfort in the science and reality of death. On the other hand, some find comfort in exploring death through more poetic and raw approaches. Zines, DIY self-published half magazines, are also a great tool to share one’s unique experience with loss such as Things better left undead: a zine about losing a friend.

How can memorabilia help us grieve?

Throughout history, people have found unique ways to remain close to the dead, often using ashes, hair, unique jewelry, and urns. This mourning brooch, intricately braided human hair encrusted with gems, is an example of how people create beautiful momentos from a difficult time while also keeping the dead physically close.

An ornate Chinese urn from the late 200s reminds us that the vessels in which we preserve the dead can be detailed, expressive, and tell a story of a life lived or perhaps a land beyond where the dead are journeying to.

Eggbeater and Urn by Richard Miller reminds us that memorial objects, while incredibly special, can also normalize grief by becoming everyday decorations around our home, or jewelry we showcase to the world.

How do we support those who are grieving?

An engraving by Henry Quilley depicts a young woman draped in a black veil, mourning at a headstone, with a devoted dog embracing her shoulder. This dark but touching scene reminds us that those who are grieving might just need to wallow in the sadness, anger, or frustration of death with a comforting support by their side. Grief does not look the same for each person and often can expose new and challenging feelings.

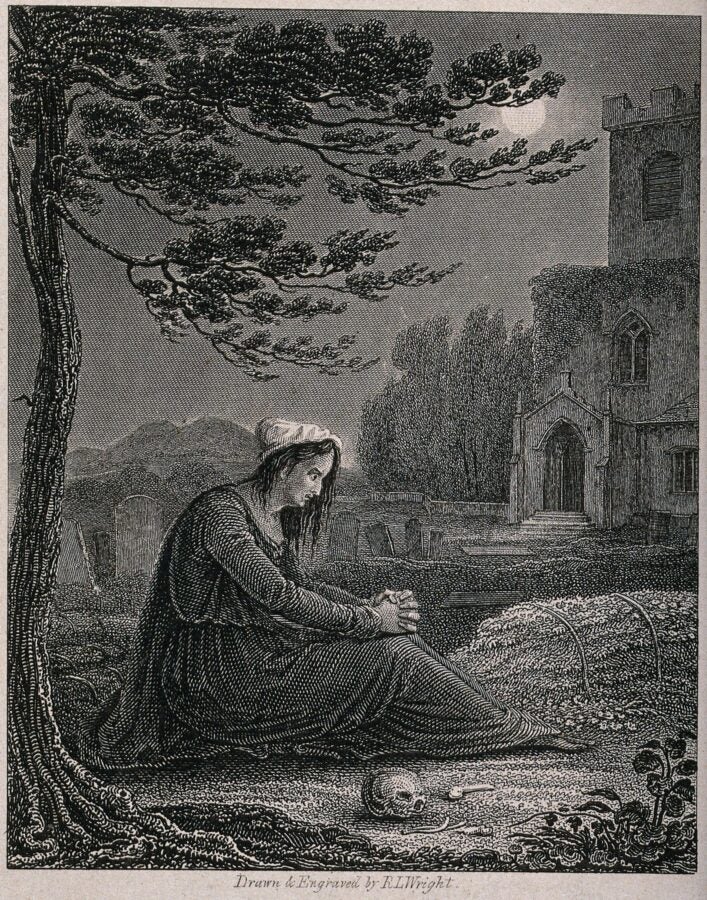

Another engraving by R.L. Wright depicts a mother reflecting, and perhaps regretting, how poorly she treated her daughter. An image created in response to ‘Satan: a Poem” by Robert Montogomery, the scene reminds us to support our grieving friends without judgement in whatever feelings may rise:

When that was dust which once an angel glow’d, / The mother’s heart return’d again, and grief, / Too late, then rack’d thy being to remorse, / Making thee all that demons could desire.

What can be learned from these various depictions of grief? Whatever it looks like, it is unique to you and your relationship to the dead. There is no wrong way to grieve.