Primary sources offer direct, unfiltered access to the voices, images, and documents that shape our understanding of the world and its history. And yet, despite their value, primary source literacy remains an ongoing challenge in higher education.

A recent webinar and report by JSTOR, Choice, and ACRL found that “60% of librarians and 40% of faculty rank student primary source literacy as challenged or extremely challenged.” Students often struggle to analyze sources critically, differentiate between primary and secondary materials, and contextualize documents effectively. Compounding these difficulties is a fragmented research landscape, where digital repositories, institutional archives, and open access collections compete for attention, overwhelming both educators and learners.

So, how can we bridge this gap? How do we empower students to confidently engage with historical texts, artifacts, and multimedia sources? The answer lies in a structured, intentional approach that integrates digital literacy, scaffolds learning, and fosters a forward-thinking mindset that embraces technologies like A.I. to support, rather than replace research.

The challenge

The traditional barriers to primary source literacy have been compounded by the explosion of digital resources. While digitization has democratized access, it has also introduced new complexities:

- An overwhelming volume of sources: Subscription databases, museum collections, institutional repositories, and open web archives create a paradox of choice. 72% of librarians and 44% of faculty cite discoverability as a major obstacle for students navigating these digital landscapes.

- Lack of awareness: Many students and faculty are simply unaware of the wealth of resources available to them. 87% of librarians and 52% of faculty report that students lack sufficient knowledge of digital primary source collections.

- Limited collaboration between faculty and librarians: Only 15% of librarians rank faculty-library collaboration as high or extremely high, meaning that students may not receive cohesive, cross-disciplinary instruction on primary source research.

These challenges highlight the need for a more strategic approach to primary source literacy that aligns with modern pedagogical methods and digital research habits.

Strategies for strengthening primary source literacy

Rather than viewing primary source literacy as a single hurdle to overcome, institutions would find it beneficial to integrate it into the curriculum as an evolving skill set. Here are some proven strategies for making primary source instruction more effective:

Active engagement through annotation and discussion

One of the most effective ways to enhance comprehension is to encourage students to engage directly with texts using annotation tools. JSTOR is integrated with Hypothesis, an annotation tool that facilitates this type of collaborative note-taking.

When you find a primary source, for example, like MLK’s “I Have a Dream” speech, you can pull the link from within JSTOR, create a Hypothesis-enabled reading, then paste the link into your learning management system LMS. From there, you can create assignments that allow students to highlight, comment, and discuss and critically think about texts together.

Scaffolded learning: Building skills step by step

Primary source literacy can be approached in stages, beginning with foundational concepts and advancing toward independent research. But what does this look like in the classroom?

To put it simply: assignments rooted in a scaffolding approach, where students are given training wheels for every phase of research. Here’s how this translates to actual assignments:

- Guided reading: Let’s say you want to teach students how to vet a primary source or understand the context it exists within. You can use Hypothesis to invite discussion by highlighting and commenting throughout a piece of text, prompting a back-and-forth discussion with your students. This exercise invites students to think deeper about what they are observing or reading, inspiring them to ask questions like “what’s the potential bias in this source?” or “would this make sense given the context of the era or decade that I am writing about?” Instructors can pull case studies from TPS Collective’s crowdsourced online instruction materials to design text-based instruction within learning management systems (LMS) to cultivate primary source literacy.

- Search engine exercises: Virginia Seymour, Head Librarian of Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) uses JSTOR to teach her students how to use search filters to find sources while saving hours. This research skill is transferable to many other types of search engines because it requires a fundamental understanding of how keywords function in yielding precise results. “I teach [how to search] on JSTOR because that’s a skill they can take to other databases, and they can take it out into Google and say, ‘Okay, I know those kinds of terms I need to be searching for now. They worked in JSTOR. I know they’re going to work in Google,’” (TPS Report, JSTOR & Choice).

- Database navigation: 64.15% of librarians surveyed in our Teaching & Learning report rated “platform navigation” as an impediment. Students are confronted with multiple user interfaces that vary in experience, content discoverability and overall design. By integrating database navigation as part of course modules, students can learn how to navigate one platform, then parlay that knowledge into learning new platforms as their research expands. This is most ideal for in-person instruction, though can be compiled into an “online toolkit” as done by Michaela Ullmann, Head of Instruction and Assessment for USC libraries. With the help of her colleagues, she created a toolkit during the COVID-19 shutdown to integrate database navigation into learning modules, testing students’ knowledge through quizzes.

Utilizing a diversity of resources and techniques

Rather than relying solely on traditional textual sources, educators can enhance literacy by integrating a variety of content types and methods:

- Use secondary sources to find primary sources. Blogs and articles thematically related to what you’re researching are a springboard to finding primary sources of interest to you. Provided that the blog/article is from a reputed website, students can find a good encapsulation of what that primary source contains and determine whether it’s the right source to use in their research. JSTOR Daily’s Reading Lists are a great way to do secondary-to-primary-source research because they are expert-curated collections of texts grouped by themes. It provides accessible entry points for students unfamiliar with primary source research.

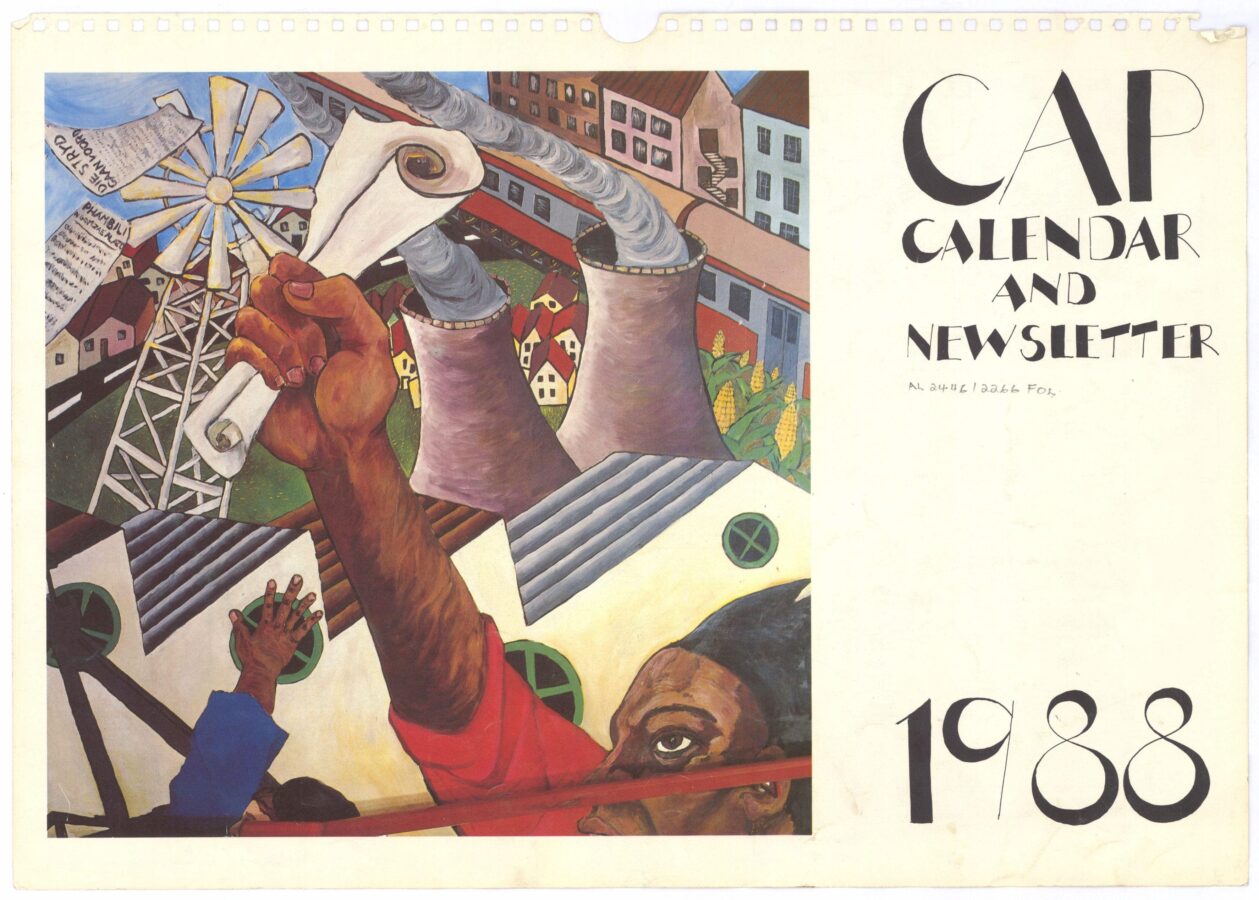

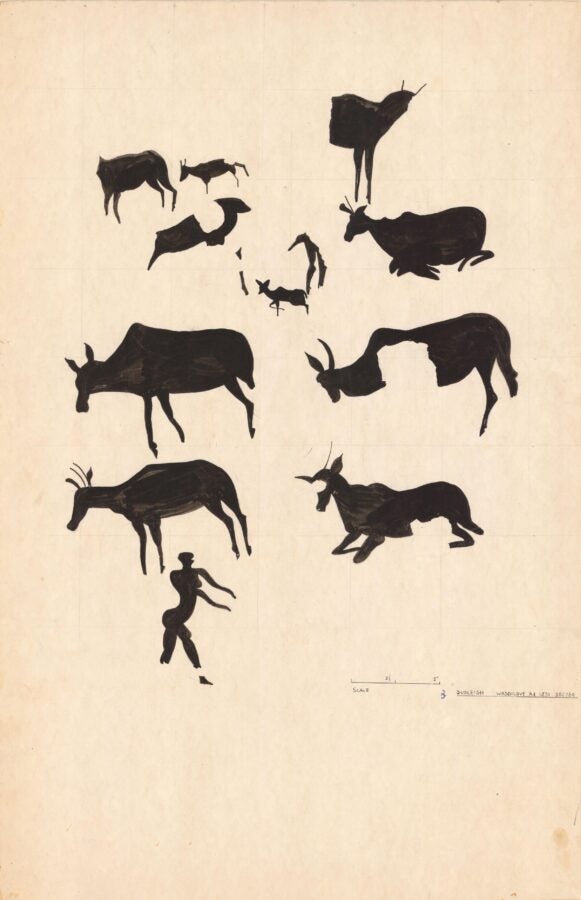

- Multimedia sources, such as historical photographs, oral histories, and documentary footage, can engage students with different learning styles. Artstor on JSTOR is a cross-disciplinary collection of images from around the world that is fully searchable, so users can easily find the specific images, videos, and audio to suit their research needs. These collections are pulled from leading museums and archives.

Encouraging faculty-librarian collaboration

Given that only 15% of librarians report strong collaboration with faculty, institutions will find that fostering these partnerships will improve primary source instruction. Possible initiatives include:

- Embedding librarians into courses to provide targeted instruction on digital research.

- Hosting faculty workshops on integrating primary sources into their syllabi.

- Creating interdisciplinary projects that require students to consult both faculty and library resources.

Integrating A.I. and other advanced technologies as research aids

Part of what makes the research process overwhelming is the abundance of databases and content aggregators. Just 12.91% of librarians surveyed in our TPS report believed that students knew how to properly use a database, a belief further supported by only 23.79% of students reporting a feeling of comprehension on how to use digital content to meet their research needs.

JSTOR’s interactive research tool is a nascent tool that can sift through repositories of information in order to find the most relevant content faster. Get the highlights first to determine whether a larger piece of work is worth the deep dive, then find sources similar to ones you deem fit for your research, all while using conversational language in your prompts.

Examples of effective primary source literacy programs

Several institutions have successfully integrated primary source literacy into their curricula through innovative programs:

- University of Michigan’s Digital Literacy Initiative: A multidisciplinary approach that combines history, data science, and digital humanities to teach students how to analyze and interpret archival materials.

- Yale’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies: An example of how multimedia primary sources can provide deeper historical insights.

- Hypothesis annotation tool: Demonstrates how digital tools can facilitate collaborative engagement with primary sources, allowing students to engage with texts in real-time discussions.

- TPS Collective: A hub of resources and support for professors, librarians, and archivists to teach primary source research skills.

By implementing similar approaches, educators can significantly improve students’ ability to analyze and interpret historical materials.

It’s not just about us–it’s for the future preservation of important history

Primary source literacy is a fundamental skill that equips students to think critically, assess credibility, and engage deeply with historical and contemporary issues. Given the barriers to effective primary source instruction, faculty and librarians working together paves the way for structured, engaging, and accessible learning experiences.

History offers the data necessary to ultimately understand the human condition, but first, we need to have the skills to unearth history and analyze it against its cultural context.

Educators, librarians, and administrators taking an active role strengthens primary source literacy. Whether through JSTOR’s curated teaching tools, librarian-faculty partnerships, or structured literacy programs, now is the time to invest in building research skills that will serve students well beyond the classroom.

Our JSTOR Teaching & Learning Report covers a range of barriers to digital literacy followed by detailed outlines of assignments and modules to improve each barrier. In addition, you can read about real examples provided to us by librarians and professors from universities across the country. This is a report you will want to bookmark.

If you’re an auditory learner, give our recent webinar a listen on your commute or lunch break.