For faculty and librarians, the challenge has never been a lack of information. The challenge is curation, integration, and the meaningful application of knowledge. Digital primary sources are not just repositories of historical documents; they are tools for intellectual discovery, engines for critical thinking, and catalysts for scholarly dialogue. And yet, their potential remains underutilized in many classrooms and research settings.

Primary vs. secondary sources: Understanding the foundations

At its core, a primary source is the raw material of history—a firsthand account, an original document, an artifact untouched by retrospective interpretation. Think of the difference between reading James Madison’s personal letters and reading a historian’s analysis of them. The former invites interpretation, skepticism, and discovery. The latter, while valuable, filters the past through a modern lens.

This is why primary sources are necessary; they establish proper entry points to understanding an event, without taking you through a maze. When you write about Solomon Northup’s experience of 12 years as a slave, you start from his autobiography, then expand in concentric circles to other secondary sources to accurately paint the snapshot in history you’re researching. But, it is imperative to start from the source of truth — which is Northup’s autobiography.

This is why digital archival is vital to maintain the integrity of qualitative research.

In contrast, secondary sources—scholarly articles, textbooks, documentaries—analyze and interpret primary materials. They provide context, but they do not invite students to construct their own narratives, or to engage in intellectual forensics. That’s where digital primary sources become essential.

The case for digital primary sources in higher education

Rethinking research: Why raw data matters

A well-chosen primary source complicates narratives rather than simplifies them. It forces students to become historians, scientists, or cultural critics—to assess credibility, recognize bias, and contextualize meaning. Consider a classroom debate on climate change:

- A secondary source summarizes decades of environmental research.

- A primary source—say, a 19th-century scientist’s field notes—reveals how theories evolved, how biases influenced conclusions, and how knowledge is constructed over time.

For example, you can use the secondary source that summarizes a longitudinal study showing how human activity exacerbates global warming changing climates in regions around the world. The primary source offers more nuance into the why, how theories of the past evolved to today, and how human perception of climate change has shifted, which in turn affect the severity with which we view climate change as an issue. Both are needed to give layers to an argument. This shift from consuming knowledge to constructing knowledge is transformative. It teaches students to interrogate what they read.

From passive reading to active engagement

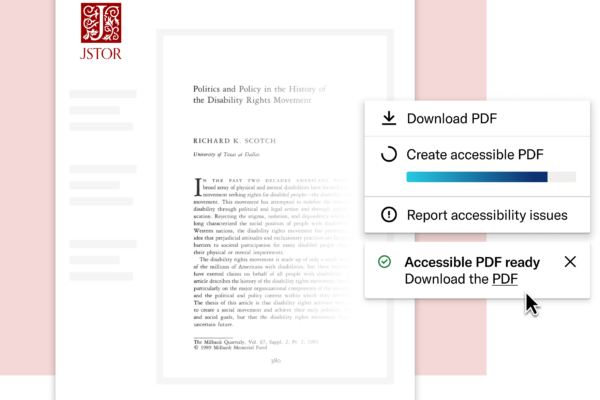

Digital primary sources are interactive landscapes for discovery. With the advent of digital annotation tools like Hypothesis for JSTOR, students can now:

- Highlight key passages and annotate texts collaboratively, layering interpretations on top of one another.

- Compare multiple versions of a document, tracking how ideas evolve across drafts.

- Engage in real-time scholarly discussions, breaking down complex texts into digestible insights.

This is a pedagogical shift as much as it’s a technological upgrade — yet at the same time, changes in tech drive necessary adjustments to pedagogy. With information saturation comes the need for information access. Otherwise, learning becomes an act of participation, not passive absorption.

Beyond the archive: making primary sources a daily practice

For many faculty members, the challenge is knowing how to integrate primary sources without adding to an already overwhelming workload.

Some strategies include:

- Embedding primary sources into assignments: Instead of assigning a textbook summary of the Civil Rights Movement, have students analyze original protest letters, Supreme Court rulings, or firsthand news reports.

- Encouraging comparative analysis: Ask students to contrast primary sources from different eras, cultures, or ideological perspectives to see how narratives shift.

- Leveraging digital collections: JSTOR and other platforms offer curated digital primary sources across disciplines, allowing instructors to craft custom reading lists and interactive lesson plans.

The key is seamless integration—using primary sources not as add-ons but as the foundation of inquiry-driven learning.

How digital primary sources are reshaping higher education

The Choice and JSTOR Teaching and Learning Report outlines real-world examples of how digital primary sources are reshaping classrooms. Here’s just a snapshot of a few to think about:

- In a literature course, students dissected early drafts of modernist novels, tracing how authors refined themes, character arcs, and narrative structures.

- In a political science seminar, archival government documents allowed students to compare official rhetoric versus behind-the-scenes policy discussions.

- In a STEM curriculum, historical lab reports helped students understand scientific discovery as a process—one full of revisions, failures, and breakthroughs.

These exercises train students to be researchers, analysts, and independent thinkers—skills that extend far beyond academia.

The future of digital primary source integration

As digital archives continue to expand, the role of faculty and librarians will involve even more curation, contextualization, and critical engagement.

For educators looking to harness the full potential of digital primary sources, the Choice and JSTOR Teaching and Learning Report provides a roadmap that highlights best practices, innovative pedagogies, and the shifting landscape of digital scholarship.

Rethink your approach to teaching and research

What would your classroom look like if students engaged with knowledge as detectives rather than passive readers? How would your research evolve if your starting point was the raw materials of history, rather than interpretations of those materials?

The answers lie in digital primary sources. And education depends on how we use them.

If you’re a teacher, enhance your curriculum by integrating JSTOR.

If you’re a librarian, give your institution access to the world.