When I was an art history student during my undergraduate studies, I frequently used JSTOR and Artstor. These platforms were invaluable – allowing me to access articles, books, and images on a wide range of topics. I remember the excitement of discovering new research and the sense of connection it gave me to artists and scholars around the world. Years later, as a museum worker, it is incredibly rewarding to be contributing to this resource from the other side. Canadian, Inuit, and Indigenous artwork remains underrepresented in standardized art history textbooks, and I hope that the inclusion of WAG-Qaumajuq’s collections will provide greater context and visibility for these important artworks, reaching new audiences and inspiring further scholarship.

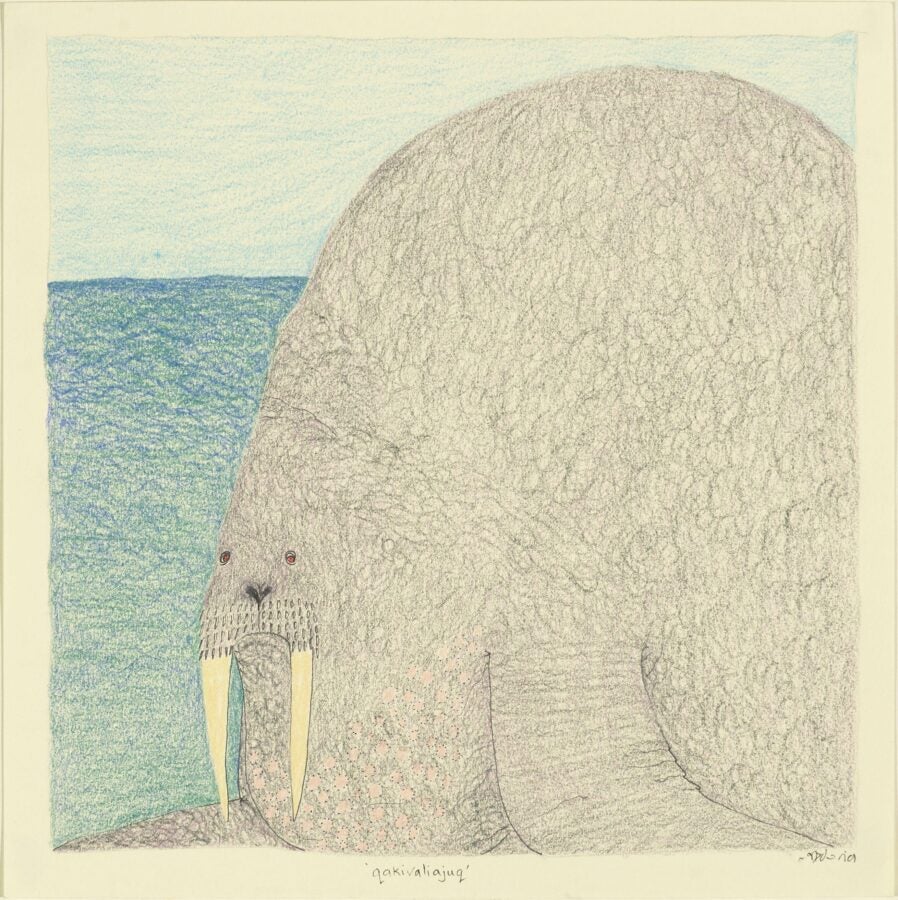

I was first introduced to Inuit art when I moved to Winnipeg from Massachusetts. Upon visiting the WAG, the first work that captured my attention was Iola Abraham Ikkidluak’s The Man Who Turned into a Walrus (2006-532.1 to 4). I was immediately drawn in by the vibrant green stone, and Ikkidluak’s expert craftsmanship in using the stone’s natural textures to highlight the smooth sheen of the figure’s parka and the contrasting roughness imitating fur on the hood and pants. As I learned more about the piece, I discovered that the artist had left a story inside the walrus’ pail. It reads:

A man ate some walrus meat and after he ate it, his head became a walrus head. He had to eat like a walrus and dive under water to get his food. But he was slower and got to the bottom after all the other walruses had eaten. He complained about this and was told to kick from the sky and dive so he’ll go faster. That helped him swim faster and allowed him to reach the bottom with the other walruses.

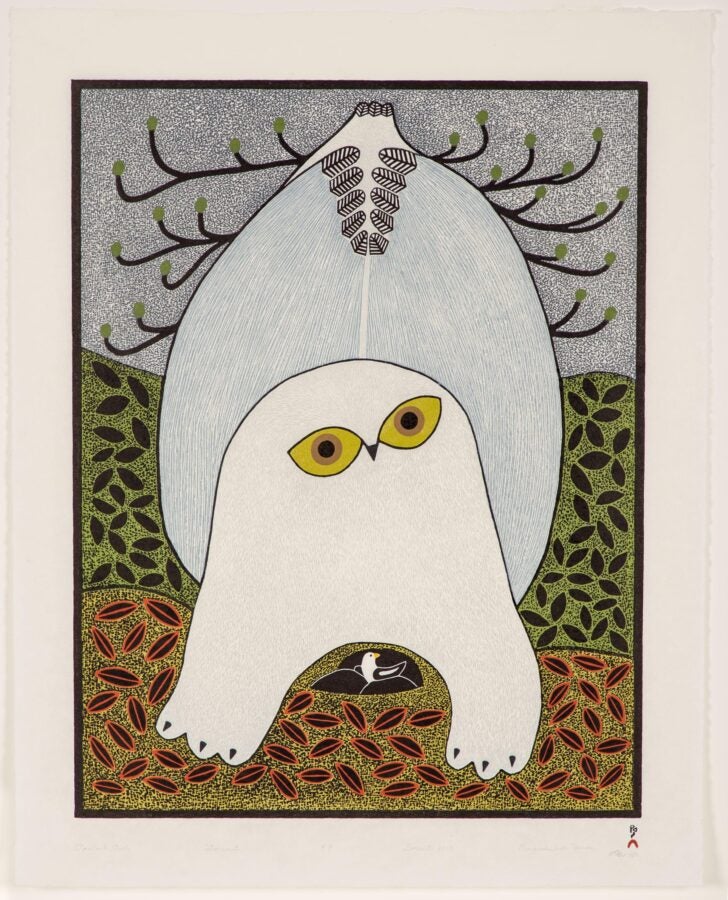

This introduction to Inuit art ignited an appreciation within me that has only intensified over the years. My admiration has since expanded to encompass a wide range of other artists and their distinct works. Through this journey, I have come to understand the vast and ever-evolving creative landscape of Inuit art and artists whose innovative practices are frequently misunderstood or relegated to being static and historicized in southern commercial art markets. The richness of Inuit art continually challenge these perceptions, revealing a dynamic and contemporary force within the global art scene.

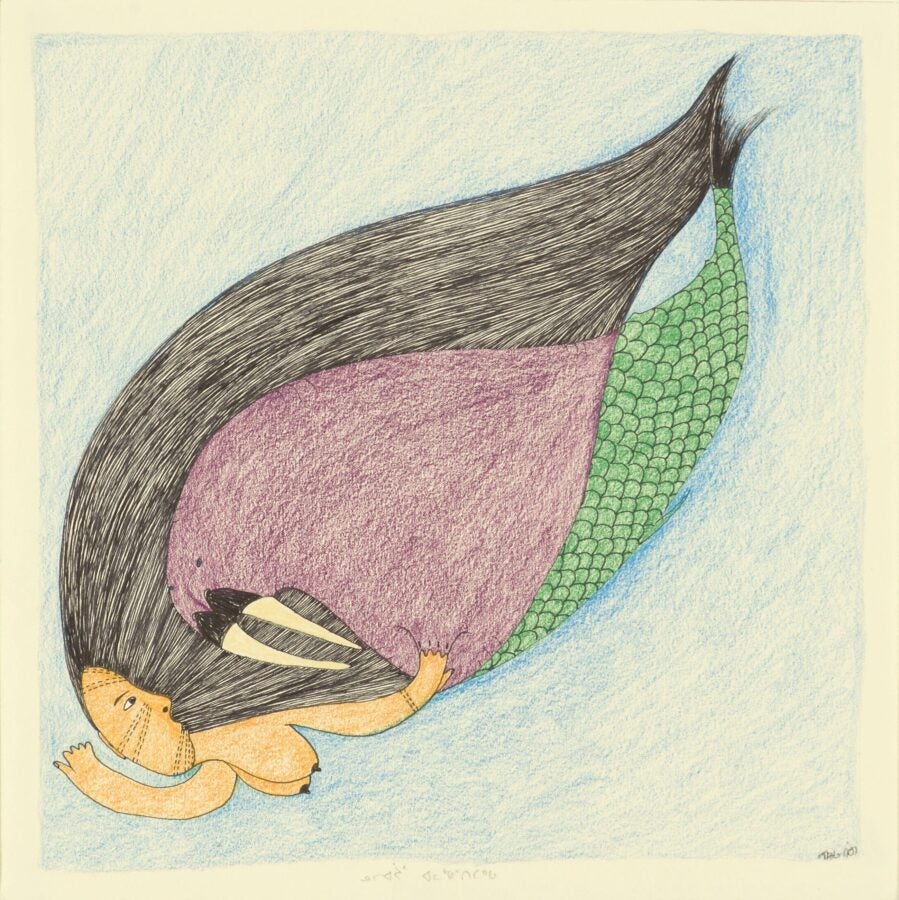

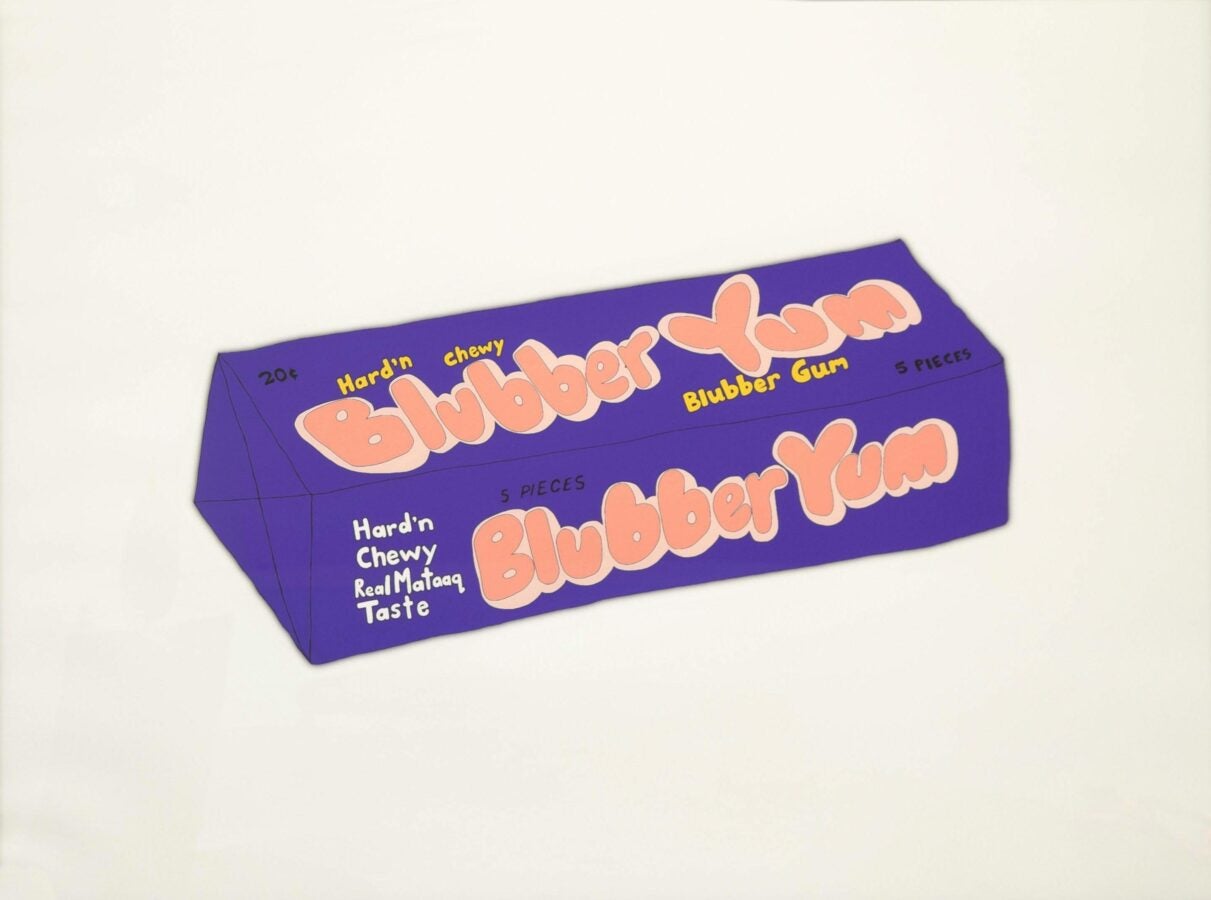

Some of the standout artists whose work has resonated with me include Ningiukulu Teevee, whose colourful and playful works on paper invite viewers to embrace wonder and imagination. Megan Kyak-Monteith’s dynamic and engaging video installations present thought-provoking narratives, often blending traditional elements with modern techniques to explore themes of identity, culture, and social justice. The extraordinary sewing skills of Fanny Arngnakik Arnasungaaq transform duffle and thread into wall hangings that seem alive with texture, creating deeply tactile and expressive works. Michael Massie’s inventive use of materials speaks to a unique and personal dialogue between the artist and the objects of his creation, while Tarralik Duffy’s digital drawings and soft sculptures provide humour while demonstrating a critical lens at underlying societal issues, among many others, engages with profound themes of personal and collective identity through art that is at once visually captivating and intellectually stimulating. These artists, along with many others continue to inspire me and bring meaning to my work as a museum professional.

As the Registrar & Collections Manager at WAG-Qaumajuq, I have the privilege of working with the incredible art collection every day. Seeing these artworks up close, learning their stories, and engaging with community members is one of the most rewarding aspects of my work. Inuit art is deeply tied to history, tradition, and lived experience, yet it is also continually evolving, reflecting contemporary practices and cultural shifts. Through our partnership with JSTOR, I am thrilled that more people will have the opportunity to engage with these works, regardless of where they are in the world.

WAG-Qaumajuq houses the largest public collection of contemporary Inuit art globally, and ensuring these works are accessible beyond the Gallery’s walls is a responsibility I take seriously. By sharing these images through JSTOR, we hope to introduce a wider audience to the incredible range of Inuit art and foster further appreciation and research. In addition, I hope users find new favourite artists to follow and artworks to carry with them past their lives in research.

While this project has started with inclusion of Inuit art, our long-term goal is to expand our holdings on the platform to include a broader representation of Canadian art, further amplifying the voices of diverse artists and communities. This initiative is part of our broader commitment to accessibility, research, and digital innovation. As more images become available, I hope that students, researchers, and art enthusiasts will discover and connect with these artworks in new and meaningful ways. It’s exciting to think about the impact expanded access can have—how it can inspire future generations of artists, academics, and museum professionals to engage with Inuit art and its rich cultural narratives.

Finally, we welcome any additional information that community members may have about specific pieces in our collection. Many of these artworks hold deep personal and cultural significance, and we recognize the vital role that community knowledge plays in enriching our records and ensuring proper attribution to artists.

The Artstor team has been fantastic to work with—accommodating, supportive, and understanding of the challenges we face as a small team. Their collaboration has made this process smooth and rewarding, and I look forward to continuing to expand access to our collections through this partnership. And I have to give a personal shout-out to my colleague Sydney Murchison for getting these images and data together and uploaded to share with the world.