Reintroducing Parole for Rehabilitation

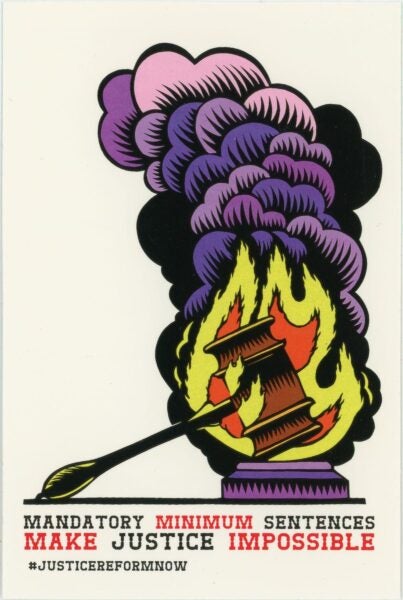

Roger Peet. Justice Reform Now — Mandatory Minimum Sentences Make Justice Impossible. 2017. Courtesy of the Richard F. Brush Art Gallery.

About the author: Phillip Vance Smith II is the editor of The Nash News, the longest-running prison periodical in North Carolina, and Compassion, a newsletter for incarcerated individuals. He is also the co-author of The Prison Resources Repurposing Act, and his writing has been published in the North Carolina Law Review, Prison Journalism Project, the Humanist, Walk in Those Shoes, and elsewhere. Phillip has been serving life without parole at Nash Correctional Institution since 2002, where he works as a visitation photographer.

If I could change one thing about the carceral system, I would reintroduce merit-based parole, instead of forcing people to serve mandatory minimum sentences, so that the incarcerated could earn their way out of prison through work or education.

I know firsthand how America’s reliance on mandatory minimum sentencing schemes can fail those returning to society, because it happened to me.

My story

On December 30, 2000, the then North Carolina Department of Corrections released me into homelessness after I had served about 14 months for an assemblage of petty, non-violent crimes.

Two weeks before my release date, I told my case manager that I had nowhere to live. One day before my sentence ended, the case manager informed me that he could find no homeless shelter to take me in. They were all full for the winter.

When North Carolina set me free, homelessness forced me to find a place to sleep my first night out, the worst way to begin a new life. Less than 90 days later, authorities arrested me for murder following what was dubbed a drug deal gone wrong.

Bad decisions caused my troubles. I own that. But the conditions compelling my horrible choices could have been better. If so, I would have never returned to jail.

Systemic Injustice

North Carolina eliminated parole in 1994 with the implementation of the Structured Sentencing Act, which introduced mandatory minimum sentencing. This move also eliminated the one mechanism ensuring newly released people left prison with the basics, such as a place to live, because permanent housing was a requirement of parole.

If I had been paroled out under North Carolina’s repealed system of parole, prison officials would have been forced to release me to a transitional house, at the very least. Indeed, I was released into a worse condition than when I went in.

Proponents of tough approaches to criminal justice will argue that states hold no responsibility to assist released people. For them, we are receiving the just desserts for crimes we committed. I argue that such an attitude has created a steep nationwide recidivism rate and caused crimes that could have been prevented.

North Carolina recognized that this problem and passed the Justice Reinvestment Act (JRA) in 2011. The JRA imposed a mechanism called post-release supervision to every released felon. Unlike discretionary parole, which allows early release based on good behavior, post-release supervision automatically reduces a prison sentence by 9 months, regardless of the incarcerated person’s merit. If the released person violates the conditions of post-release, they must return to prison and serve the reduced 9 months.

Reform efforts must go further

The JRA evidences North Carolina’s recognition that some forms of parole are necessary. Renaming parole “post release” is more than a play on words. systems of parole compel rehabilitation by placing the responsibility of change on the incarcerated person. Early release serves as the goal, or incentive, resulting from a showing of personal change. Post-release supervision merely shifts the mandatory minimum release date by 9 months. It cannot create a safer North Carolina in the way merit-based parole could.

A solution to this problem is not complicated. In 2020, I co-authored the prison resources repurposing Act (PRRA), a legislative proposal that would extend release to those serving life without parole after the completion of educational, vocational, and behavioral goals over a 20-year period. The PRRA does what North Carolina’s current sentencing scheme cannot: offer rehabilitation in exchange for the incentive of release.

Without such an incentive, more people will end up like me. On March 8, 2002, a jury convicted me of murder. I was sentenced to life without parole. I have served about 22 years. I don’t know if I will ever be released. My station of hopelessness spawned the idea for the PRRA.

North Carolina House Representatives sponsored the PRRA in the 2021 and 2023 state legislative sessions. It failed to pass both times, yet I keep fighting because I believe in change, and hopefully, my words will help change the carceral system.

Sources:

The Justice Reinvestment Act , North Carolina General Statute 15A-1368

Phillip V. Smith, II & Timothy W. Johnson, “Hope for the Hopeless: The Prison Resources Repurposing Act,” N.C. L. Rev. 713(2022).

Hope for the Hopeless: The Prison Resources Repurposing Act

Editor’s Note: Last fall, Phillip workshopped different ideas for Second Chance Month with us. His insights helped us understand that the hopes and fears of people currently incarcerated are inextricably linked to conditions beyond the prison. Inaccessible housing was referenced in more than half of all submissions as either a contributor to an arrest or as a barrier to building a life post-release, and 30% volunteered that it delayed their education or made it more challenging to maintain enrollment in post-secondary education.

Phillip’s resilience and persistence to make connections with people and drive change from shared stories and experiences embodies the spirit of our work this April. His work is a testament to the transformative power of writing. Phillip did not include a biography, so I copied the biography published here.