How one ghost story competition continues to haunt the humanities—just in time for Halloween

This is a spooky installment of a series exploring the enduring importance of the humanities. Stay tuned for more insights on why the humanities still matter.

The night that inspired Gothic literature

In 1815, a volcanic eruption in Indonesia released a massive cloud of ash and particulates, large enough to affect global weather. Temperatures plummeted, causing frosty conditions and torrential rain across Europe, North America, and Asia for months. The result? Failed crops, widespread hardship, pestilence, and famine.

Against these events, we begin in 1816–known also as the “Year Without a Summer” or “Eighteen-Hundred-and-Froze-to-Death.” At a mansion near Lake Geneva, Switzerland known as the Villa Diodati, a gathering took place. Lord Byron, accompanied by his traveling physician John Polidori, hosted writers Mary Shelley (then Mary Godwin), Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Claire Clairmont. Clairmont, Byron’s mistress and mother of his unborn child, had orchestrated the introduction between Byron and the group. The timing of this get-together, however, was far from ideal. For three days, the group remained indoors, confined by the unseasonable and mysterious inclement weather.

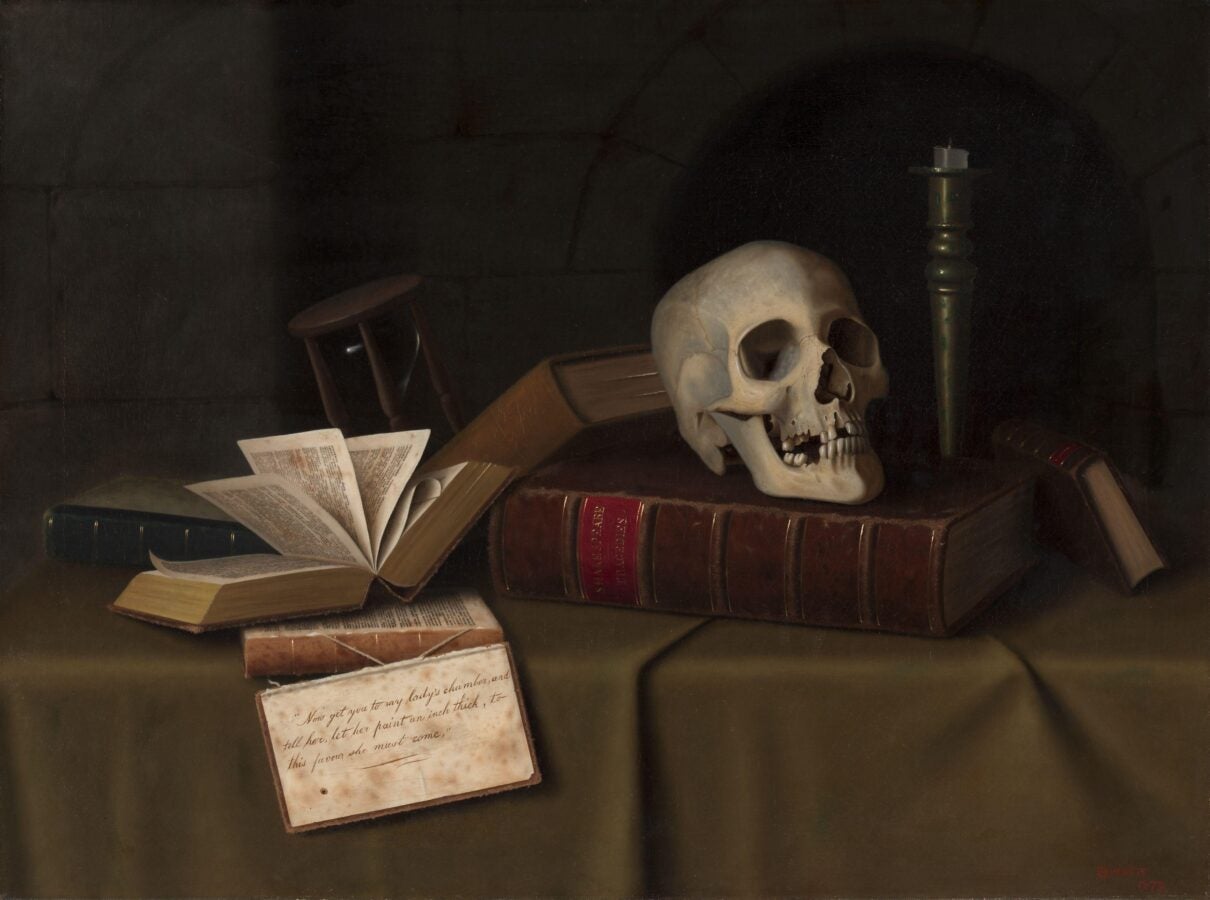

To pass the time one evening, having already read aloud eerie and violent narratives like those in Jean-Baptiste Benoît Eyriès’s Fantasmagoriana, Lord Byron presented the group with a challenge: to write chilling tales of their own. From this spirited competition emerged two progenitors of modern horror, science fiction, and fantasy.

The spark of being: A birth of Gothic masterpieces

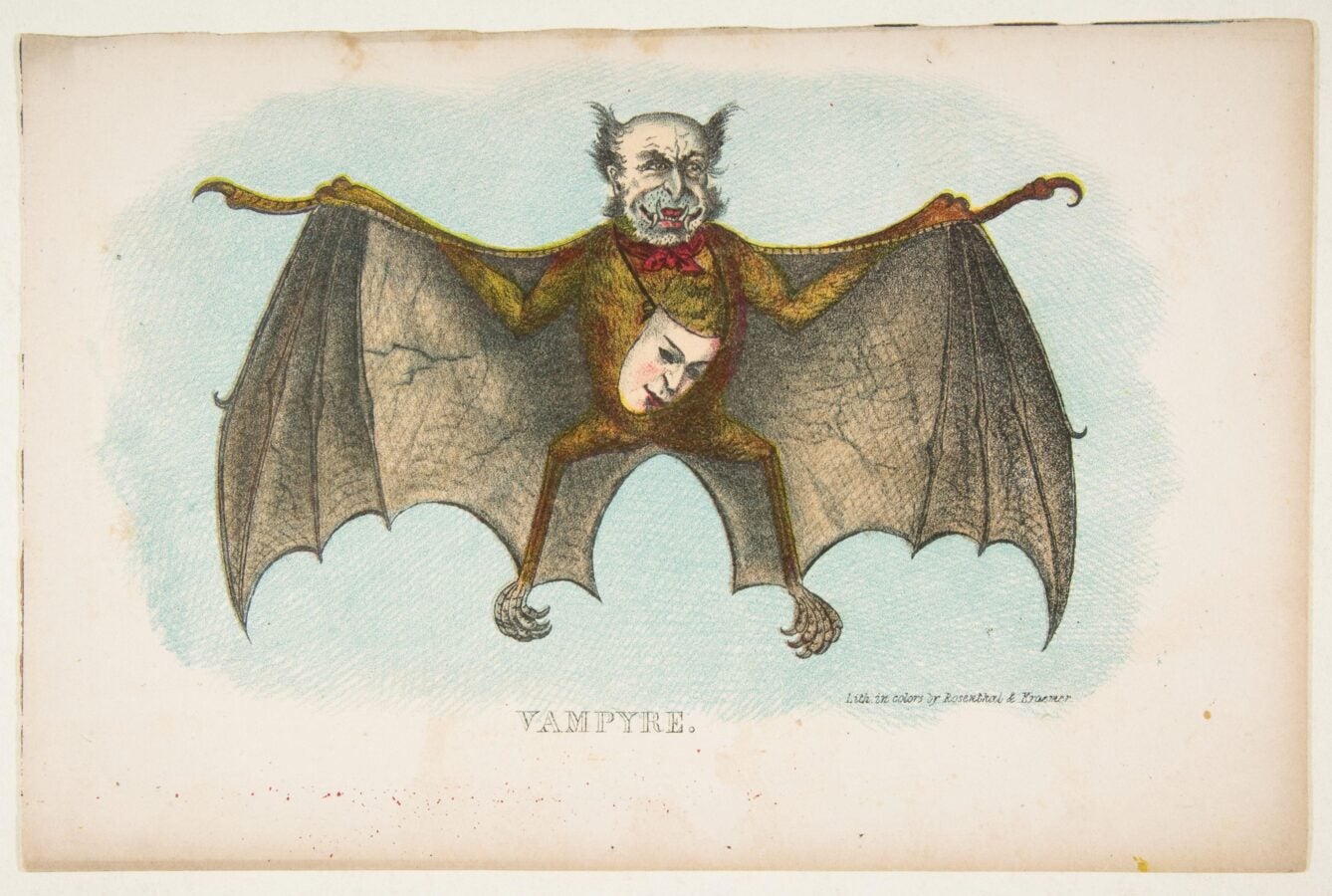

This meeting of minds and its tempestuous backdrop produced three significant works: Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley, The Vampyre by John Polidori, and A Fragment by Lord Byron. Percy Shelley and Claire Clairmont’s participation in the friendly competition did not bear such fruit.

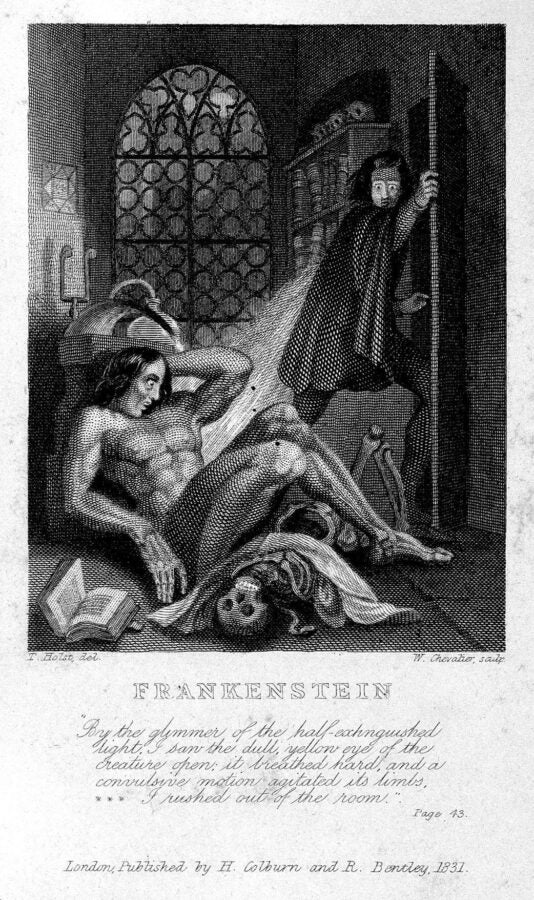

Mary Shelley, the daughter of two highly regarded writers, struggled quite a bit to conjure an idea of her own. She hoped to prove worthy of her patrimony by devising a story that evoked the same fears and concepts as the narratives read aloud by the group. After a time, inspired by conversations between Byron and Polidori around the reanimation of corpses, her story dawned on her as though it haunted her itself–she envisioned a man breathing life into lifeless, later besieged by the waking result of his efforts. From this image, she produced Frankenstein, one of the most enduring literary works of our time.

Lord Byron, on the other hand, quickly abandoned his entry for the competition. Dubbed A Fragment and later published against his will in a collection of poetry, the incomplete epistolary follows the narrator’s companionship to an older man during an eastward journey. The older man, plagued by an unknown illness, requests the narrator bury him and return to the location later, but bids him not to tell others of his death. While the story abruptly ends there, Polidori noted that Byron intended for the older man to return to life as a vampire.

Inspired by Byron’s Fragment and fixated on stories by and about Byron besides, John Polidori began writing The Vampyre. Lord Ruthven, a seductive nobleman modeled after Byron himself, is accompanied by the tale’s narrator and later discovered to be the very vampire described in local legends. This work is considered the first of its kind to neatly package elements of vampirism into a single piece of fiction. It is nearly considered folkloric, with contemporary vampires still mirroring the characteristics of Polidori’s Ruthven.

Illuminated themes

Each of the aforementioned three stories explores questions of life, death, and the unknown–questions relevant to modern readers and the human condition at large. They also speak to broader themes of interpersonal relationships, class dichotomies, and ethics.

Frankenstein, in particular, is a vehicle for a wide span of inquiry. It touches on the moral ethics of scientific ambition, the consequences of assuming what some perceive to be God’s role in creating life, and even the potential devastating impact of men’s actions on the women in their lives. Shelley’s novel continues to influence conversations around deeply human topics, transcending time to produce literary and philosophical dialogue.

The Vampyre, on the other hand, can be surfaced in conversations around the predatory nature of ruling classes. The work demonstrates the manipulation of power and privilege, exploring how those of a higher station may exploit the vulnerable. The story also touches on the complex relationships between men, namely the dynamics of dominance, dependency, and betrayal.

In addition, both works can be employed to investigate Romantic fascinations with the supernatural and the unknown. They both embody Gothic tropes of anxiety and repression, questions of agency and free will, and indices of societal decay. Together, Frankenstein and The Vampyre remind us of literature’s power to probe the deepest questions of human existence, offering enduring insights into the ethical, social, and existential dilemmas that continue to shape our world.

Eternal light: How collaboration and creation reflect the humanities

Whether through the lens of scientific hubris in Frankenstein or the predatory allure of aristocracy in The Vampyre, the stories brought forth from that fateful gathering in 1816 remain relevant, as they continue to challenge readers to consider the consequences of unchecked ambition, the complexities of human relationships, and the social structures that shape our lives. Their enduring presence in literary and philosophical discussions speaks to the core function of the humanities–to explore, question, and better understand the forces that define our existence.

Beyond the inspiration we continue to derive from these timeless stories, the events around their creation also speak to core tenets of the humanities, those of collaboration and human connection. The gathering at Villa Diodati reminds us that intellectual exchange and shared creativity can lead to works that endure over centuries. The humanities thrive on these interactions, as ideas evolve and grow through debate and dialogue.

So, this Halloween, why not embrace that same spirit? Gather your friends, swap ideas, and try your hand at writing a spooky story of your own. Who knows—your own ghostly gathering may ignite something that stands the test of time. As we just learned, some of the greatest stories began with a friendly challenge and a dark, stormy night.