About the author

Vy Thang is a lifelong learner currently pursuing his Bachelor’s Degree in the Liberal Arts through Evergreen Prison Education Program (EPEP) offered by the Evergreen State College. He was incarcerated in 1997, at the age of 17, and is currently housed at the Stafford Creek Corrections Center in Aberdeen, Washington.

Editor’s note

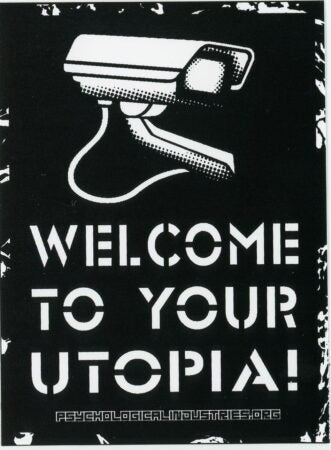

This blog post is inspired by Vy Thang’s compelling essay, “How Getting an Education Became My Purpose,” and the phone interview that followed his submission for JSTOR’s Second Chance Month 2025: Reclaiming Identity Through Learning. This initiative encouraged currently incarcerated individuals to share how education influenced their identity, purpose, relationships, or worldview. Vy’s narrative serves as a powerful lens through which we can explore the disruption of the idealized notion of utopia, particularly in the context of the corrections system, definitions of community, and intergenerational trauma.

As I accepted the first of three collect calls from inside the Stafford Creek Correctional Center, Vy Thang quickly set the stage for me on what he has been studying.

“The theme for this quarter was utopia, utopia societies, you know, and, the first thing that, … I thought about was, you know, I equated utopia … with authoritarian, like thought, you know, society … like something that Cambodia went through with Pol Pot, you know, someone’s vision for everybody else…I mean not in a good way, but you know, docile, uneducated … things that, you know, I want to ask my parents about eventually … I don’t want to hurt them or traumatize them … but I feel like that’s my purpose … I want to tell their story before that story’s gone.”

And so began a 90-minute conversation about Utopian ideals, Pol Pot, the value of liberal arts education, podcasts, and shared experiences.

But what is a utopia? Sir Thomas More first introduced the term in his 1516 book Utopia, which depicted an island with its own distinct social systems. Since then, utopian visions have significantly varied, yet they often reflect the values of their time and serve as critiques of existing societal structures. They refer to an envisioned perfect society or community in which social, political, and moral ideals are fully realized, leading to harmony and prosperity for all. In the context of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge regime, which Vy’s parents survived, and which he is wrestling with this quarter in school, the concept of utopia takes on a perilous and personal meaning.

“There’s things on my mom’s side of the family that … I don’t know about, you know, like how many brothers and sisters that she had. I don’t even know that, you know, what’s her mom’s name? … I mentioned it a little bit in [what] I wrote … my mom and dad, they were part of Pol Pot’s utopian vision, you know, and they weren’t, they didn’t, they didn’t come together out of love, you know, they were forced together. Basically, to create me … growing up, I didn’t understand it at the time because, you know, I always felt distant from my mom, but you know, I understand why now … when she sees me … she sees something Pol Pot wanted, you know, this new society that he wanted to create.”

Pol Pot aimed to radically transform Cambodian society into a classless agrarian utopia, where intellectualism and education were suppressed in favor of a simplistic rural lifestyle. His vision sought to establish a homogeneous society free from perceived corruption and foreign influence. However, the pursuit of this utopian ideal led to catastrophic consequences, including the genocide of millions, forced labor, and widespread suffering.

Vy shared with us that this is the first quarter he has had access to JSTOR and could use it to find articles like “Portrait of a Dictator” that offered insights into Pol Pot’s regime. Throughout his essay and our conversation, I was moved by his deep desire to understand his parents’ experiences more profoundly and, by doing so, his own place within this complex and personal history. He writes, “Any Cambodians that had an education would have been killed. Whether it be lawyers, doctors, teachers, or musicians—they were all killed. So, I wondered If my parents may still, subconsciously—have it in their mind that education somehow equals danger or death? But for me, this realization made me even more determined to become something that the Khmer Rouge tried to eradicate—an educated Cambodian man.”

Utopian views overlook the complexities of human nature and societal dynamics, resulting in unrealistic expectations of perfection and potential exclusion. This is particularly relevant within the corrections system, where existing is a nuanced individual journey rather than a static destination. For Vy, education transcends the classroom as it is applied to personal narratives and understanding of self. He says, “Education is not just about getting a degree; it’s about widening your knowledge and absorbing the truth about life.” Later, he adds, “… there’s a lot of vocational classes here, and you know, they, they want you to get out and get a job because they think that just getting a job is gonna keep you out of trouble, but you know it’s teaching a person to be rational, to, to think … that’s what I think creates a better person.… When you think about what you’re doing and society as a whole… why things are the way they are, you know?” Vy’s pursuit of knowledge through a liberal arts education illustrates how education can empower individuals to engage with their surroundings critically and develop community where they are.

“So guys come in here … and I kind of motivate them to do something instead of just sitting down and playing cards or just doing nothing all day, you know … some of them just shake their heads, you know, yeah, not for me, but, but then there’s some that I start talking and explaining and there’s some that’s actually interested … I don’t think there’s gonna be a problem creating [the next] cohort, you know, because it’s not, it’s not just me, the other guys in class … it’s like perfect. It’s just everyone is just on the same page, and everyone cares.”

Vy’s words encourage us to embrace the complexity of human experience and recognize that progress lies in our ability to learn, grow, and support one another.

When I asked Vy if access to education had changed his relationship with staff, people on his unit, or those closer to him, like his roommate, he responded, “When you do nothing but study, and go to school you see … like the people that, you know, don’t have the same values as you or you know, the same minded as you and they tend to back off a little … and the staff, they kind of just leave you alone because they know … what you’re not about.” Vy and his fellow scholars are disrupting the very utopian views they are exploring this semester. Their journey highlights an environment where education serves not only as a pathway to employment but also as a space for personal growth, critical engagement, and meaningful connections within the complexities of the human experience. More importantly, for Vy, it becomes a space to connect with those around him and include them in the journey.

As our time together came to a close, he added, “I feel like I’m just now starting to wake up, you know, I understand myself a bit more. … I’ve been on this educational journey for a long time, but it took like this class to make me actually see things a little differently, you know … I still have my faults, and I’m still learning, and there are things that I have a hard time with, and I don’t, don’t get it. But I’m open. I’m gonna stay on this path.”

Additional resources

Watch the full interview with Vy Thang here:

- Listen to a recording of the conversation

- Read a transcript of the interview (PDF)

- Read a PDF of Vy’s essay

The opinions and views expressed in these recordings, art, and posts are those of the authors and do not represent, reflect, or imply endorsement by ITHAKA.