Emilie Hardman, research lead for archives and special collections at JSTOR and curator at Reveal Digital, has spent her career navigating the complex and evolving challenges of contemporary archival work: ever-growing collections, mounting backlogs of unprocessed materials, limited resources, and shifting research expectations. From positions at MIT to the University of Arizona, she has worked to promote and facilitate the widespread use of primary sources.

When she tested JSTOR Seeklight, the AI-powered tool developed as part of JSTOR Digital Stewardship Services, she saw the potential for a shift in how archives approach these challenges. Could AI help reduce bottlenecks in processing? Could it surface hidden connections and patterns in collections? Most importantly, could it free up time for archivists to focus on the work that requires their expertise—contextualizing materials, shaping narratives, and deepening engagement with researchers and communities?

“If collections are not discoverable, they are effectively hidden to researchers,” Hardman says. “By using JSTOR Seeklight to make collections more findable and usable, we can help people activate them in all sorts of new ways.”

That potential—AI as a tool that assists rather than replaces archival labor—is what excites Hardman most. But realizing that promise requires careful implementation, guided by insights from archivists like her.

The challenge: Hidden collections, backlogs, and the digital dilemma

At Reveal Digital, which develops open primary source collections from underrepresented 20th-century voices of dissent, Hardman collaborates with advisors to source and shape collections. In this role, she often comes face to face with a common challenge: traditional archival description was designed for physical materials, where records are grouped and described at a broader level rather than individually. While this approach has long been standard, it can be a barrier in a digital environment, where researchers expect item-level metadata to support search and discovery.

“Traditional archival description was never designed for digital search,” Hardman explains. “Archival practice focuses on describing materials at higher levels, but to find material in the digital research ecosystem really requires more detailed metadata.”

This gap has created a bottleneck. While the More Product, Less Process (MPLP) approach, which was broadly adopted starting in the mid-2000s, prioritized access over detailed description, it often left materials under-described.

“MPLP helped make collections nominally discoverable,” Hardman explains. “But minimal description often means losing contextual details that make materials fully usable. It was always meant to be a starting point, with descriptions refined over time—but that’s rarely possible given the resource constraints archives face.”

Meanwhile, researcher expectations have also changed. Many scholars today expect digital access and struggle with traditional finding aids—structured inventories that provide high-level descriptions.

“I’ve done user testing for archives products and seen undergraduates look at a finding aid and not understand it,” Hardman recalls. “They’d say, ‘I see this is described, but where is it? I’m clicking everything, and nothing’s happening. Something must be broken.’ But it’s not broken—it’s just not digital.”

Born-digital materials pose their own set of challenges. “We still have repositories that are excellent at processing paper but struggle with digital workflows,” Hardman notes. As a result, “Digital preservation sometimes looks like putting a hard drive in an acid-free box.” With terabytes of data—emails, PDFs, word processing files, websites—archivists face an unprecedented scale of processing work.

In this high-volume, high-stakes environment of the contemporary archive, AI offers new possibilities—if it is deployed in ways that align with archival values.

AI in service of the archive

Hardman sees the potential for AI to be used as a tool to allow archivists to focus on the more complex, important work they’re trained to do—building context, shaping narratives, interpreting the record, and otherwise activating collections.

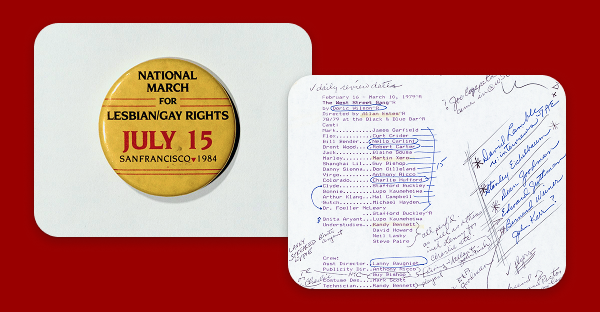

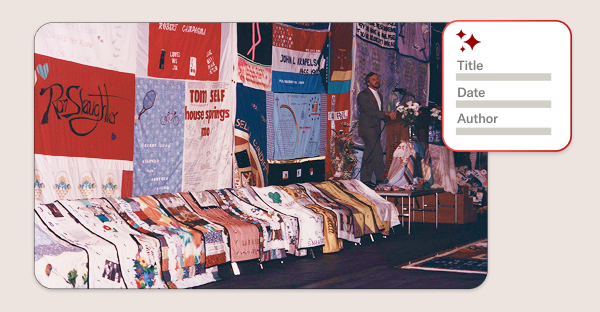

She first glimpsed this possibility when she ran materials from Reveal Digital’s HIV, AIDS, and the Arts collection through JSTOR Seeklight. The collection—a vast assemblage chronicling artistic responses to the epidemic—includes hundreds of playbills, one of which Hardman used in the experiment.

Unlike some AI systems that retain or train on input data, JSTOR Seeklight does not store or learn from the materials it processes—a critical safeguard that made Hardman comfortable using it for this collection.

Typically, manual description would entail describing a group of playbills (e.g. at the collection, series, or box level)—in most cases, it would be rare to have basic metadata about an individual play’s title, playwright, and theater company. But when Hardman let JSTOR Seeklight analyze it, she was stunned by what it uncovered. “In addition to producing core metadata, it also automatically identified and extracted the names of people I hadn’t even realized were involved in the play,” she recalls.

In doing so, JSTOR Seeklight surfaced hidden layers of connections within the playbill that had gone undocumented in the existing description. Hardman recalls thinking, Oh my gosh, that person was connected to this other thing. That person was connected over here. Oh, they were also advertising for this show that was really pivotal in AIDS awareness.

Rather than replacing archival labor, this was a moment where AI was extending it—enhancing what was possible.

“I want AI to handle pulling out names, titles, places, and structuring or encoding the data—but I want people doing the work of telling the story,” says Hardman. “That’s where our expertise belongs.”

Reckoning with the past, undoing erasure, and acknowledging the trade-offs

Archival description has never been impartial. Decisions—about what gets described and how—shape historical memory.

“There’s this persistent myth that archival description is neutral,” Hardman says. “It’s not. Every finding aid, every metadata record is shaped by human decisions. AI makes those choices more visible—which means we have an opportunity to be more intentional about addressing them.”

This is especially true for collections from historically marginalized communities, which have often been under-processed, misclassified, or excluded from archival systems altogether. “Because resources go to collections most in demand, people who didn’t live long enough to build careers in the arts aren’t known—and therefore, they aren’t in demand. They are silenced again and again through the lack of description, access, and use,” Hardman says.

At its best, AI can surface names that were never indexed, connections that were never documented, and records that were never available simply because no one had the time to describe them. But AI does not correct for bias on its own—it can also replicate and reinforce exclusions already present in archival data. That’s why human intervention is critical. “AI can help identify problematic language or under-described communities in finding aids or catalogs,” says Hardman. “But responsibility still lies with us—it requires careful human consideration and community consultation.”

Beyond bias, Hardman is mindful of AI’s environmental costs, noting that “AI systems require vast amounts of energy and water to train and maintain. The environmental impact is obscured behind images of frictionless digital efficiency—but it’s something we need to account for in our decision-making.” For Hardman, the key is balancing AI’s benefits with its trade-offs.

Looking ahead: Insights for skeptics and visions for the future

For archivists wary of AI’s role in their profession, Hardman offers a perspective grounded in both pragmatism and care: “Skepticism is appropriate. AI is not a magic fix. It can’t replace the deep cultural, historical, and ethical work that archivists do. But it can give us more time to focus on those things—to move beyond rote, mechanical tasks and into the realm of storytelling and knowledge-building.”

In the long term, she envisions AI expanding its role in archives—not as a replacement for human expertise, but as a tool to augment it and broaden access. “If we can reduce the labor required for description, we can increase digitization,” says Hardman. “If we can increase digitization, we can increase access. And if we can increase access, we can democratize archival research in a way that hasn’t been possible before.”

That’s a future she’s excited about.

In Hardman’s words, “We’ve spent so long treating descriptive work as clerical. But it’s art. It’s storytelling. It’s building knowledge. AI can take on the rote work—but the meaning? That still belongs to us.”