This blog post is part of a series dedicated to celebrating JSTOR’s 30th anniversary. Explore the whole series.

In 1995, JSTOR launched with a mission that felt radical at the time: digitize scholarly journals and make them accessible online to researchers and educators everywhere. As we mark JSTOR’s 30th anniversary in 2025, we’re looking back at how it all began and why that vision continues to matter, especially for the humanities and social sciences.

From overcrowded stacks to a new model for access

The idea for JSTOR took shape in late 1993, during a routine board meeting at Denison University. William G. Bowen, then president of the Mellon Foundation and a trustee at Denison, was evaluating a proposal to expand the campus library to make room for more journals. Instead of focusing on funding for new shelves, Bowen posed a bolder question: What if the journals didn’t need to be stored on-site at all?

At the time, the first web browsers were just emerging. Bowen proposed digitizing the full backfiles of academic journals and making them widely accessible online. This was suggested as a scalable solution to help relieve the overwhelming pressure on libraries, while also securing long-term access to interdisciplinary scholarship.

JSTOR evolved into a pilot project to digitize core journals in economics and history. Economics and history were selected as disciplines for the pilot because they were widely taught, had strong nonprofit publisher support, and offered contrasting research and technical challenges. This would demonstrate the archive’s potential to serve interdisciplinary needs across a range of institutions.

Born from the library, built for the long term

In 1995, JSTOR was officially incorporated as a nonprofit, with Kevin Guthrie as founding president. Early support from the Mellon Foundation, the University of Michigan, and charter institutions like Bryn Mawr, Denison, and Williams enabled JSTOR to digitize nearly a million pages before its public launch. The American Historical Review was the first journal to join, followed by titles from the American Economic Association, the Econometric Society, and leading university presses.

Building JSTOR: Experiments, missteps, and breakthroughs

Turning JSTOR from an idea into a functioning archive wasn’t immediate. Early grants from the Mellon Foundation were received quickly to meet this rare urgency and sponsor hands-on collaboration between funders and technologists. Much of the early software was borrowed from University of Michigan’s previous digital library projects, but adapted for scholars in the humanities. This meant prioritizing readability, context, and ease of use above all. The initial interface was simple but effective, featuring Michigan’s blue-and-maize colors and allowing basic browsing and keyword search.

Our team quickly learned the limits of digitization at the time. Microfilm was low in quality, so we switched to scanning from paper and often discovered torn, incomplete, or mismatched journal volumes. A planned partnership with a third-party indexer fell through, forcing us to rethink how we handled metadata and citation fidelity. We also debated whether to abandon high-resolution page images for more lightweight, searchable text formats like SGML, but ultimately stayed the course in favor of scholarly trust and accuracy.

Even quality control proved a massive undertaking: some journals took months to finalize due to formatting issues or missing pages. These early growing pains shaped how JSTOR would approach its mission going forward: with care, curiosity, and a commitment to building something that scholars and librarians could rely on for decades to come.

Read more about JSTOR’s early years in JSTOR: A History by our very own Roger C. Schonfeld.

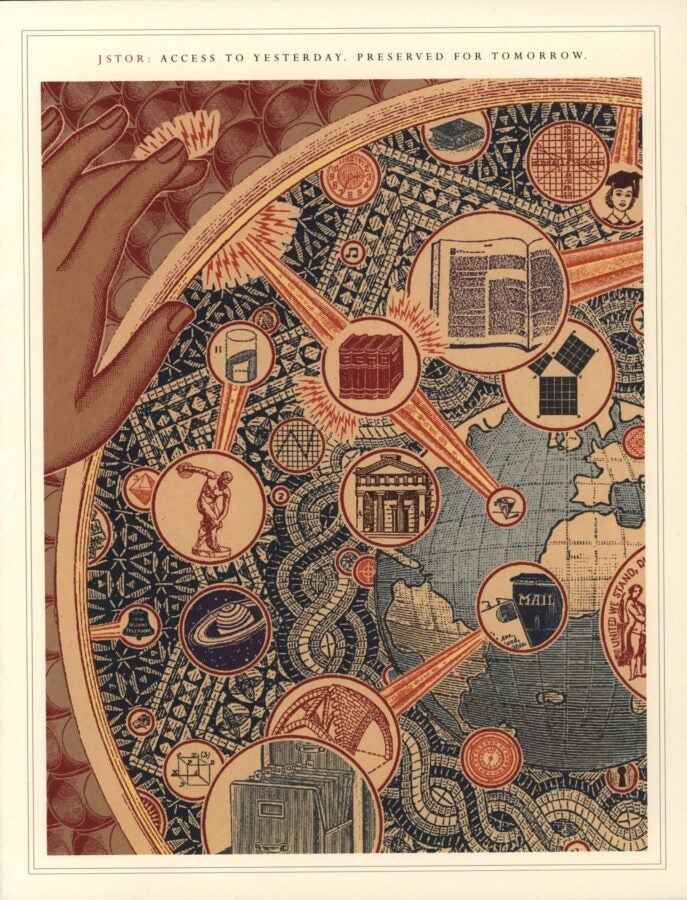

Design spotlight: A logo rooted in print and tradition

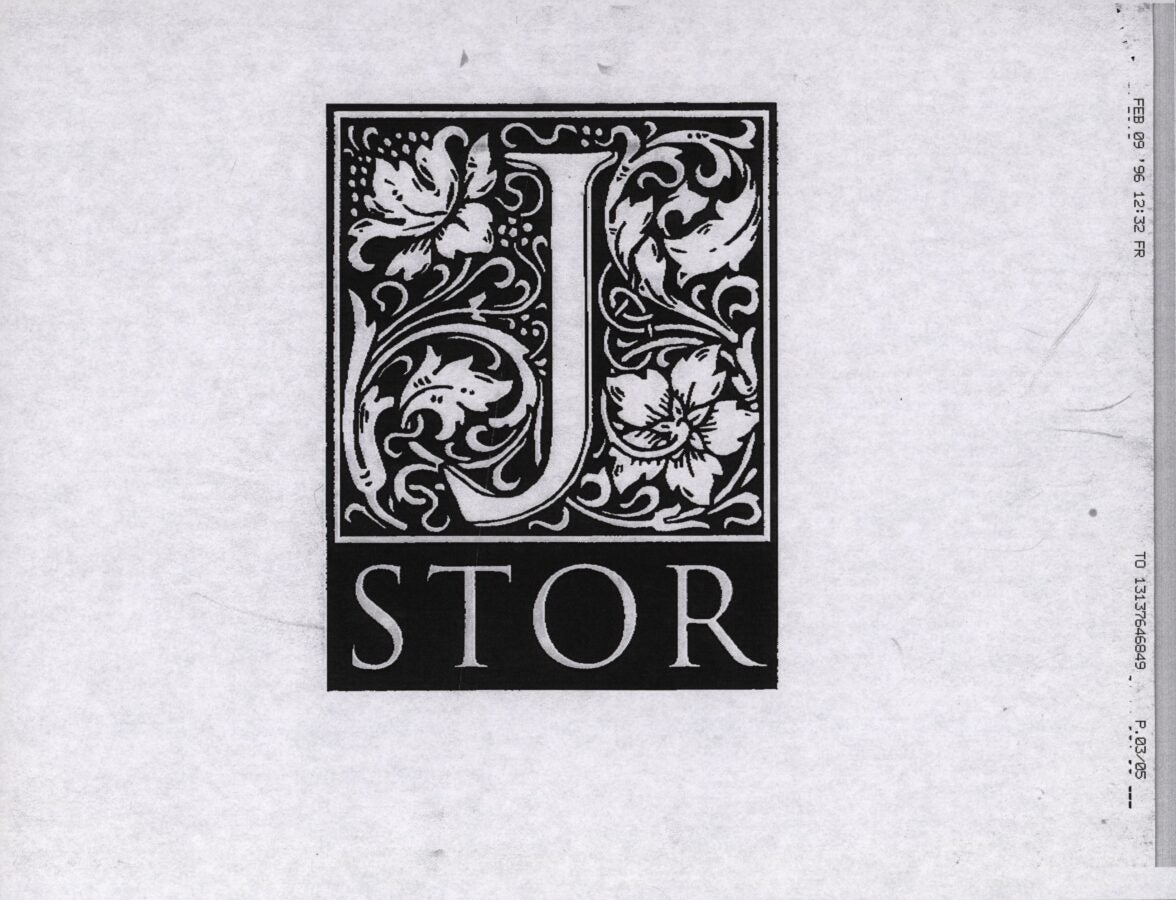

As JSTOR was taking shape in 1995 and 1996, its visual identity was crafted with just as much thought as its technical infrastructure. Designer Michael Mabry proposed the iconic floral “J” as a deliberate nod to the history of print, drawing inspiration from decorative initials used in Renaissance-era typesetting.

In a 1996 fax to Kevin Guthrie, Mabry explained his design approach: cap initials were a “strong visual link to the history and tradition of fine printing,” meant to reflect JSTOR’s digital mission and its deep respect for the printed page. Mabry saw printers, typographers, and scholars as partners in transmitting ideas to the masses, with JSTOR as the next piece.

The resulting logo, with its ornate, illuminated “J” and classical styling, bridged tradition and innovation. It signaled that JSTOR, while revering the methods of scholarship’s past, hoped to preserve and build upon it in new, enduring ways.

Why this matters, especially now

JSTOR was built at a moment of crisis: Libraries were running out of space, journal costs were rising, and smaller institutions were being priced out of access to scholarship. But behind that practical challenge was a larger question: Who gets to participate in the conversation of knowledge?

The humanities and social sciences—history, literature, philosophy, art, sociology, psychology—have long been central to that conversation. They help us understand the nuances of our culture and historical contexts. They give us tools for empathy and introspection. When JSTOR was founded, the academic journals shouldering this work were highly at risk of becoming inaccessible to those without the means to locate them.

JSTOR emerged to preserve the scholarly record and democratize the scholarly dialogue. Core humanities and social sciences content, and its availability at a large scale, are crucial to this mission. Our commitment to conserving and expanding research materials is as urgent as ever, especially at a time when access to trusted, contextualized knowledge can serve as a public good.

Looking ahead

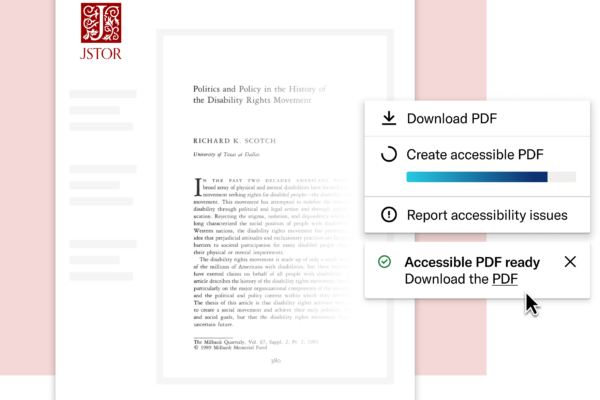

30 years in, JSTOR serves more than 14,000 libraries in 190 countries. Its collections include 2,860 journals, over 13 million articles, and millions of images and primary sources. Our founding mission, though, endures: using technology in service of scholarship and preservation.

In this blog series, we’ll celebrate that mission by sharing stories from JSTOR’s past, spotlighting collections and people who helped shape it, and imagining where access to knowledge might go next.

![A black-and-white scanned memo dated 2.6.96 from "Michael" to "Kevin" discussing the design direction for JSTOR's identity. The text reads: KEVIN, I WOULD LIKE YOU TO CONSIDER THIS DESIGN DIRECTION. DECORATIVE CAP INITIALS HAVE BEEN A DESIGN DEVICE EVER SINCE MAN HAS BEEN COMMUNICATING WITH THE ROMAN ALPHABET. CAP INITIALS ARE STRONG VISUAL LINKS TO THE HISTORY AND TRADITION OF FINE PRINTING. NEEDLESS TO SAY THAT THE PRINTER, THE TYPOGRAPHER, AND THE SCHOLAR WERE INTEGRAL COMPONENTS IN TRANSMITTING IDEAS TO THE MASSES. THE QUESTION I AM ASKING IS, SHOULD THE JSTOR IDENTITY REFLECT THE ORIGINS OF THE PRINTED PAGE RATHER THAN THE TRANSMITTING OF INFORMATION AS REFLECTED IN THE PREVIOUS DESIGN SOLUTIONS? THE JUXTAPOSITION OF THIS CLASSIC VISUAL ON THE INTERNET IS QUITE NICE. IF YOU LIKE THIS APPROACH I NEED TO REFINE THE "J". THE ORNAMENTATION HAS TO BE SIMPLIFIED, AND THE "J" NEEDS TO BE MORE DOMINANT. GIVE ME A CALL WHEN YOU HAVE A CHANCE [signature] MICHAEL](https://about.jstor.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/003-1-1171x900.jpg)