More than 2 million of the images in Artstor are now discoverable alongside JSTOR’s vast scholarly content, providing you with primary sources and vital critical and historical background on one platform.

During the nineteenth century the painting genre of the operating theater emerged—an arresting hybrid of fine art and the art of medicine. Highly specialized and hotly debated, its celebrated champion was the American artist Thomas Eakins, both appreciated and condemned for the realism which he brought most notably to his medical paintings. The Gross Clinic, 1875, and The Agnew Clinic, 1889, are his most monumental canvases among about 25 that feature medical practitioners. With images from the Carnegie Arts of the United States collection, the University of Pennsylvania University Archives, Mauritshuis, Panos Pictures, and an infusion of related imagery from two open collections—Open Artstor: Wellcome Collection and Open Artstor: Science Museum Group—we may now probe these powerful and disquieting works with clinical precision.

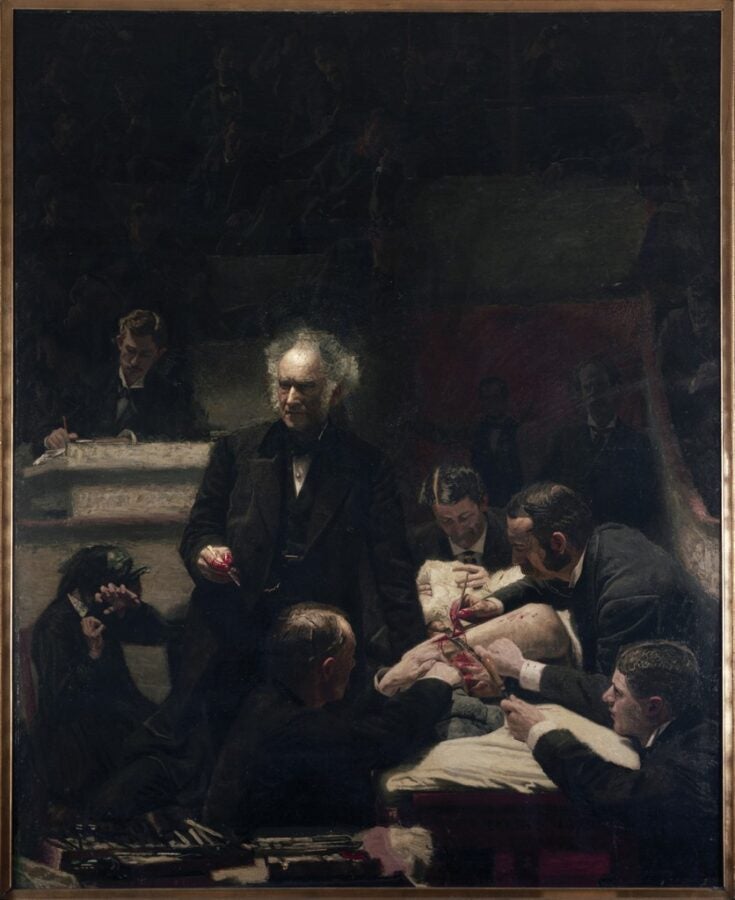

The Gross Clinic depicts Dr. Samuel D. Gross, characterized as the “emperor of American surgery,” in his element at center stage directing his assistants who perform an operation on a patient’s thigh while he also addresses his students. A woman recoils at left, the only discordant note to his authority. The setting is Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College, where the artist himself began to study medicine before choosing a future in art. On a canvas measuring about 8×6 feet, the figures approach life size.

The spectacle of surgery provided another opportunity for Eakins years later when he received a commission to portray the illustrious Dr. Agnew on the eve of his retirement in The Agnew Clinic. Self-taught (not unusual for the day), Agnew rose as a surgeon treating soldiers during the Civil War. Here the surgeon, both practitioner and orator, dominates the composition much like his predecessor Gross. The patient undergoes a mastectomy at the hands of Agnew’s assistants. As in The Gross Clinic, every individual in the painting has been identified, with the exception of the patient. The artist has included himself in both compositions at the far right margin, nearly excluded from the gallery. The horizontal format of the Agnew painting allows for the inclusion of many students befitting the commission that was paid for by them. With dimensions of 6×10 feet, the scale conveys a sense of reality.

An examination of some of the material details and differences between the two works permits us to consider the most important developments in the field of surgery during the period, the first being the relative light levels. While Dr. Gross emerges from darkness, Agnew is bathed in light. It was, in fact, during the 1880s that electric lamps were introduced to the operating room, prior to that daylight and gas fixtures provided the only illumination. Eakins’ paintings dramatically illustrate this shift.

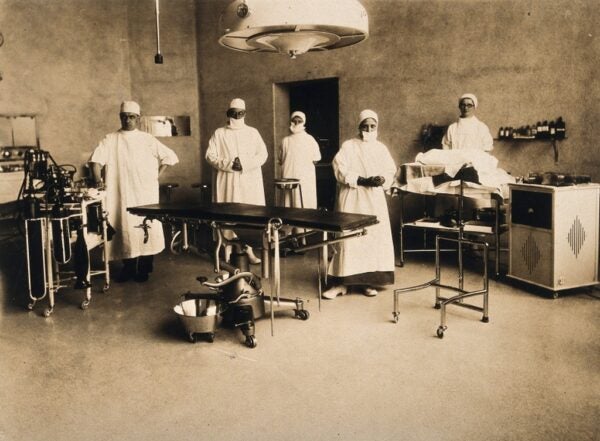

The groundbreaking medical advances that are most manifest in the works are antisepsis and anaesthesia. The penumbra of The Gross Clinic results from the low light source as well as the attire of the physicians—black jackets and dress shirts, the garb of the Victorian gentleman, in conspicuous contrast to the white smocks and aprons of Agnew and his colleagues. Around the mid-1800s Scottish surgeon Joseph Lister introduced standards of antisepsis to the field. Sterile surgical attire was gradually adopted in the operating theater among other Listerian practices, and by the 1880s decreased rates of infection were credited to the use of hygienic caps and gowns. Later innovations, masks and gloves (still absent even in the later Agnew Clinic) completed the prophylactically correct attire of the surgical staff. A photograph of a “modern” operating room includes fully suited practitioners as well as gleaming equipment made of stainless steel, a material introduced to the field around 1910–1925, essential both for its non-corrosive properties and tolerance to thermal sterilization.

Gloves enhanced the protection of both patient and surgeon. While the earliest were made of fabric, sometimes coated in paraffin, a rubber version was introduced by the Goodyear Rubber Company and William Stewart Halsted, professor of surgery, in 1889—chiefly to protect the hands of the surgeon. It was Halsted’s resident, the aptly named Dr. Bloodgood, who recorded that the rate of patient infection declined with a fully gloved team.1 A later photograph showing a technician testing rubber gloves for pinholes, a practice that is still current, reinforces the importance of an impermeable barrier.

The bizarre attire of the “beak doctor,” engineered by Dr. Charles de Lorme around 1620, was an early medical uniform used to protect practitioners from the contagion of the plague. Its full coverage, including the voluminous waxen coat and massive gloves, was essentially a medical armor. While ostensibly shielding its wearer from germs, it offered no deterrent to patient to patient infection.

Eakins’ paintings further provide historical insight into the evolution of anesthesia during the period. Ether and chloroform were successfully used to sedate patients by mid-century. Both of the clinic paintings demonstrate the administration of sedatives by inhalation, first with a cloth over the patient’s face in The Gross Clinic and with the more targeted use of a mask in the later Agnew painting. Such a device, albeit more advanced, may be seen in a metal version, 1877–1920.

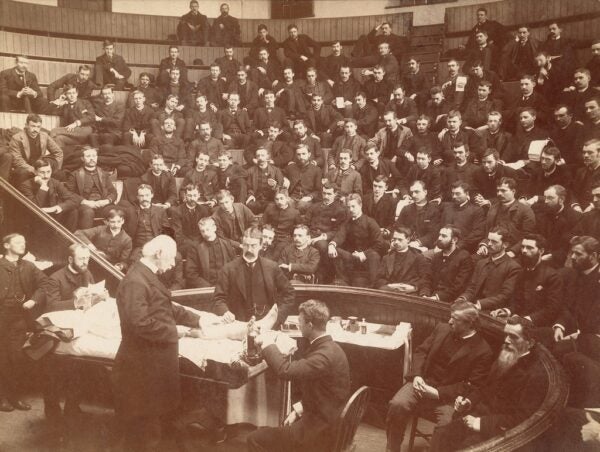

Documentary photographs of the clinical amphitheater from the era reveal how closely Eakins hewed to reality in his presentation of the players and the setting. A view of the Agnew clinic by George Chambers dated March 30, 1886, may well have been used by Eakins as a compositional aid for his painting that tightens the field of vision but largely reprises the scene.

While the approach of Eakins was thoroughly modern, his inspiration was rooted in the tradition of the paintings of the anatomy theater, notably Rembrandt’s “Anatomy Lesson of Doctor Nicolaes Tulp,” 1632.2 Eakins took his theme, composition and scale from Rembrandt for the Agnew painting. For its time, Rembrandt’s portrait was as modern as Eakins’ was for his—in its depiction of a leader of the medical community practicing and teaching his art to his students, with the graphic demonstration of Vesalian anatomy in the dissected forearm and hand at the center of the painting. In hindsight, we might contemplate the amazement of Tulp, Gross, Agnew, and Eakins were they able to grasp contemporary medical advances epitomized here by bionic hand prosthesis, the 21st-century version of Rembrandt’s hand—endowed with the full complexity of human functionality.

Related content

- Huebert, Ronald. “Performing Anatomy.” Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance Et Réforme 33, no. 3 (2010): 9–26. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43446208.

- Kirkpatrick, Sidney D. The Revenge of Thomas Eakins. Yale University Press, 2006. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1npz1s.

- Rego Barry, Rebecca. Inside the Operating Theater: Early Surgery as Spectacle. JSTOR Daily. 12/9/15.

Notes

- Lu Wang Adams, Carol A. Aschenbrenner, Timothy T. Houle, Raymond C. Roy; Uncovering the History of Operating Room Attire through Photographs. Anesthesiology 2016;124(1):19-24. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000932. ↩︎

- For the Augmented Reality experience of the Anatomy Lesson on Dr. Tulp, see Mauritshuis: Rembrandt Reality. ↩︎