Many college and university libraries have amassed special collections that hold great value for students, faculty, and researchers, and a growing number are digitizing these collections in order to share them more widely and ensure long-term preservation.

Yet, institutions often struggle to find sustainable solutions for accomplishing this work. If students and scholars can’t readily find or access the materials contained in special collections, then these items will seldom be used for teaching or research. And, without a forward-thinking plan for maintaining digital files, the long-term accessibility of these collections is at risk.

The Lucy Scribner Library at Skidmore College is solving this problem with the help of JSTOR Digital Stewardship Services. Built on decades of experience creating trusted library resources like JSTOR and Portico, these services enable institutions to make collections globally discoverable, free of paywalls, and ensure content remains accessible for generations to come. David Seiler, Head of Digital Projects and Collections for the Library, said, “By hosting public-facing special collections on JSTOR, building and cataloging select collections in JSTOR Forum, and preserving them with Portico, Skidmore is making these materials widely accessible and amplifying their long-term impact.”

By hosting public-facing special collections on JSTOR, building and cataloging select collections in JSTOR Stewardship, and preserving them with Portico, Skidmore is making these materials widely accessible and amplifying their long-term impact.

Broad accessibility

Skidmore was already using another platform to store and manage the bulk of its digital special collections. However, they’d been using JSTOR’s tool to build and catalog their visual resources and museum assets for some time, and were happy with the value of this service. So, when the college became aware of the opportunity to share collections on JSTOR beginning in 2020, campus officials decided to participate.

JSTOR is used at tens of thousands of institutions worldwide as part of the research workflow. “That broad accessibility is very appealing… It’s another venue for us to offer this work, and another point where someone could find it,” Seiler said.

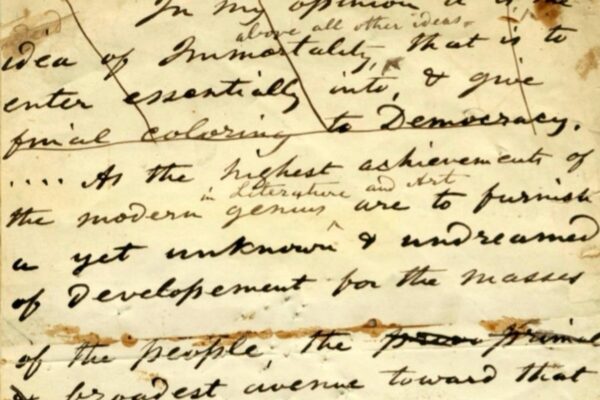

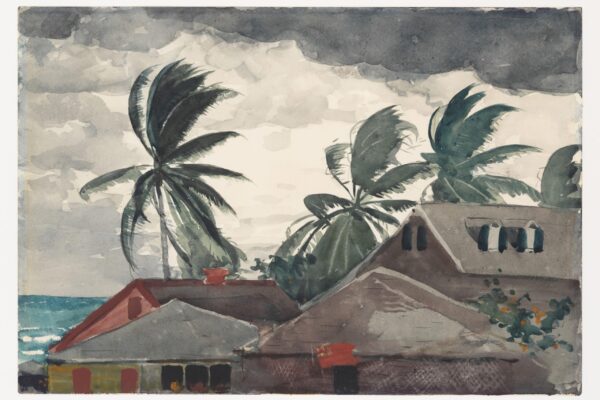

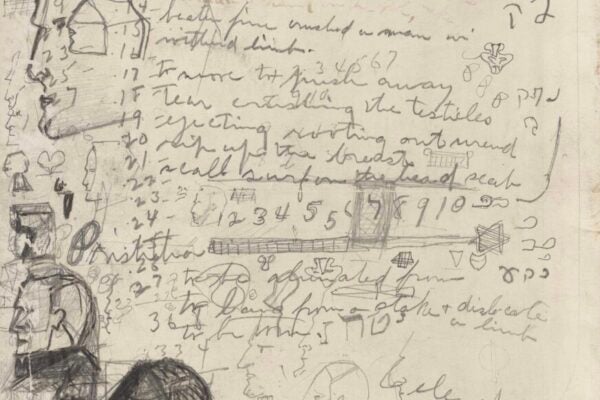

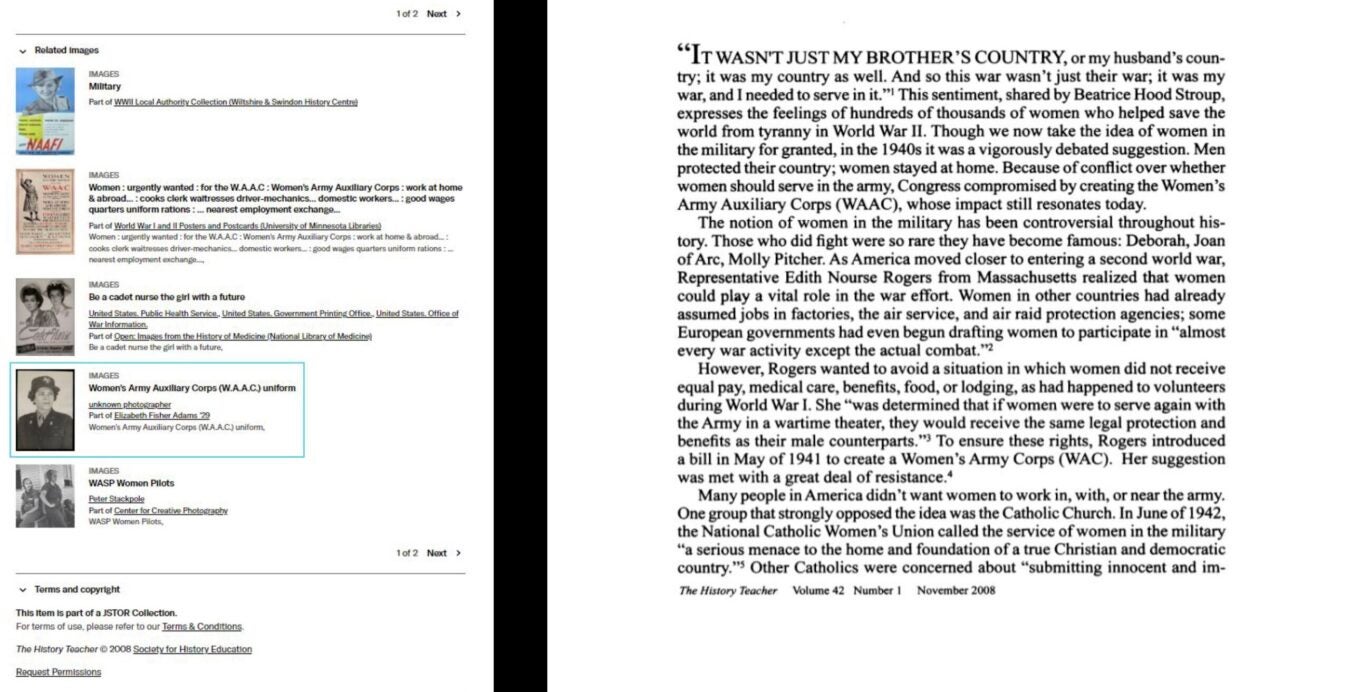

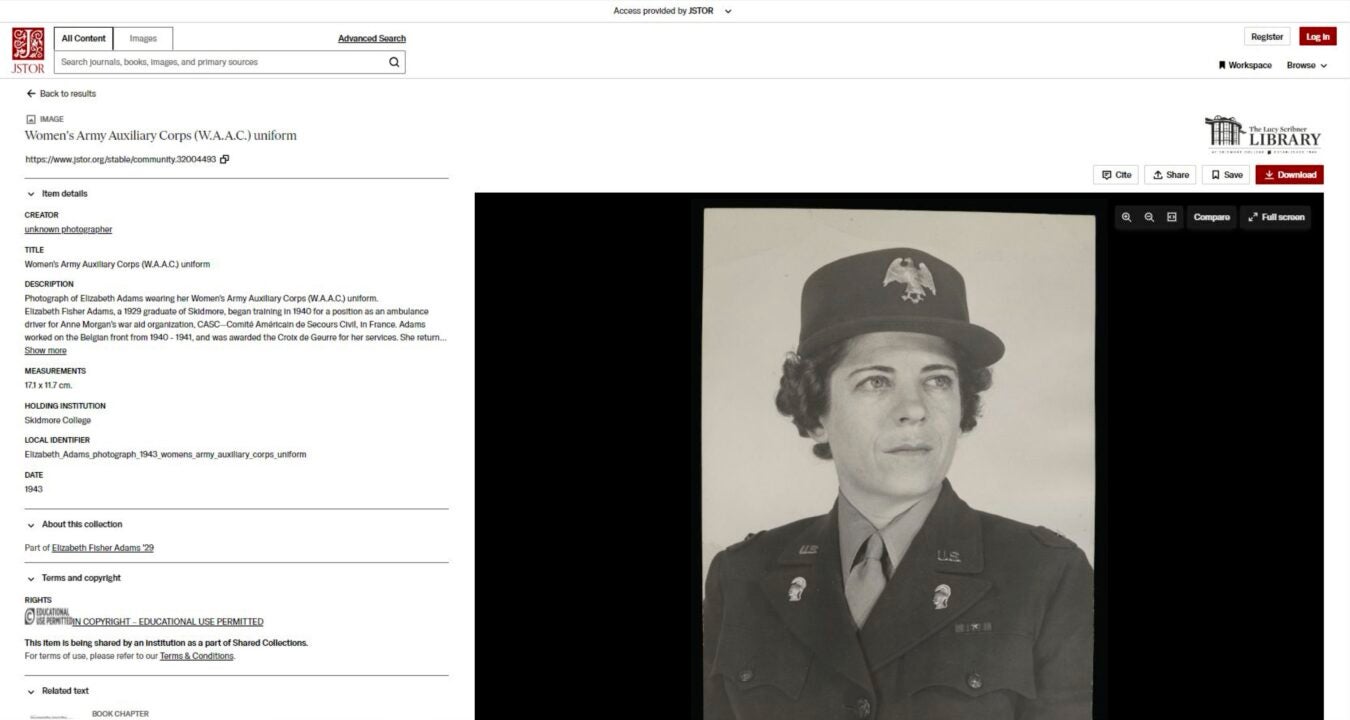

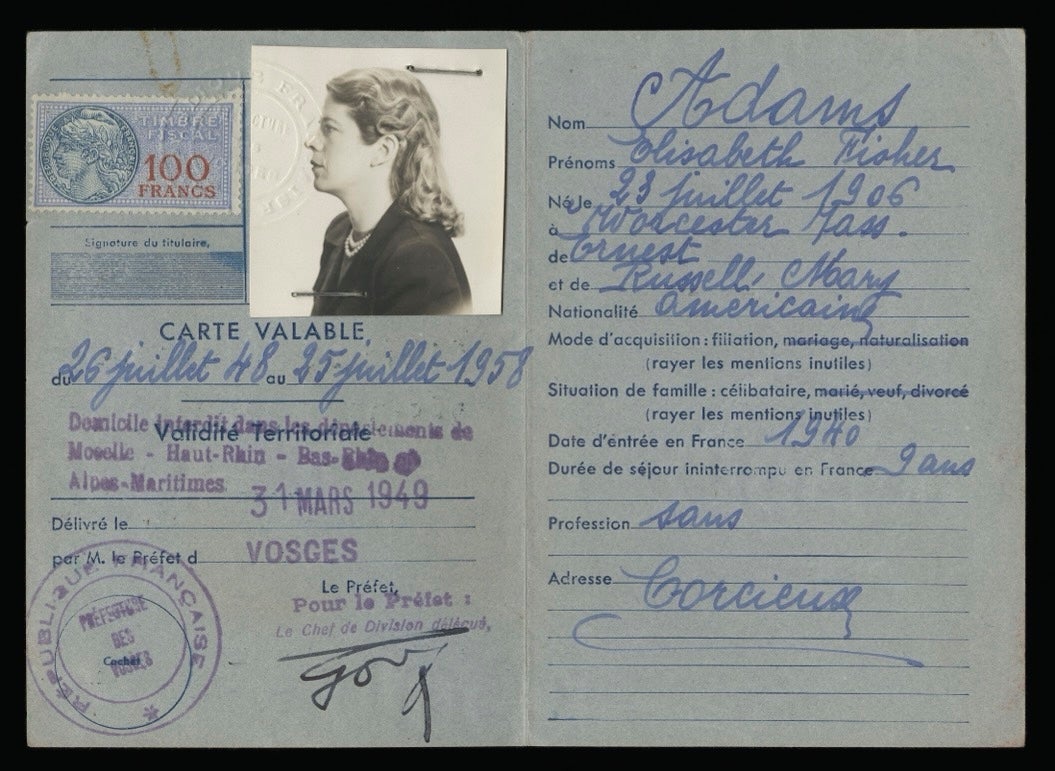

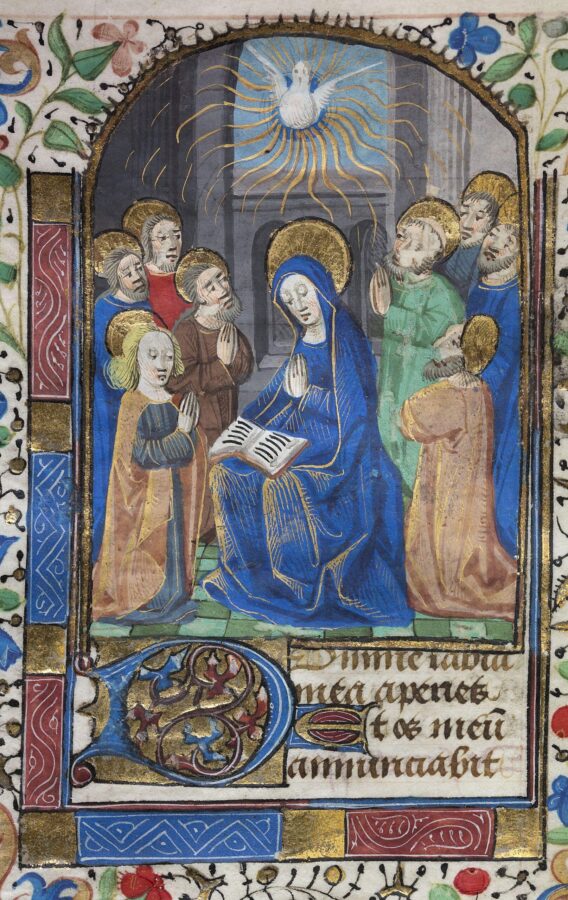

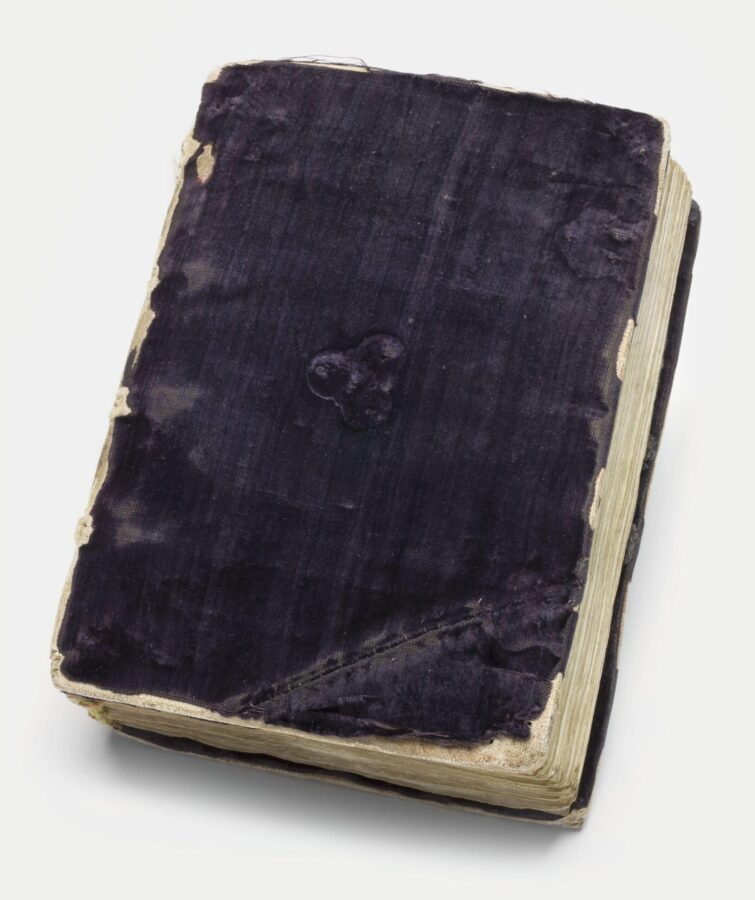

The college chose to start by sharing five special collections on JSTOR that would have a broader appeal beyond the Skidmore campus. These included a collection of nearly 1,000 photos of student life at Skidmore College from the 1920s through the 1950s; a collection of prints featuring the Saratoga, New York area; a collection of letters that include a missive from former New York Governor William Seward discussing the first-ever use of the insanity defense in a criminal trial in the United States; and the Elizabeth Fisher Adams ’29 collection of documents, photos, and letters from this Skidmore alumna’s time in France during World War II, where she served as a member of an ambulance corps.

“Not only does JSTOR have an extensive body of users, but its indexing features give librarians the ability to contextualize the materials in their special collections so that these items can be found in related topic or keyword searches within JSTOR and internet search engines at large,” Seiler said. For instance, someone searching for information on World War II in either JSTOR or Google might find the materials in the Elizabeth Fisher Adams ’29 collection.

Aside from the potential for items in special collections to be discovered more easily, preservation with JSTOR Digital Stewardship Services offers active preservation of digital materials through a secure, managed process.

By leveraging lessons learned from the 25 years of Portico preservation, JSTOR Digital Stewardship Services ensures long-term accessibility by transforming content into durable formats and adapting to evolving technologies. This proactive approach guarantees the integrity and usability of digital assets for future generations. “We don’t have a dedicated archivist on campus,” Seiler said. “So, it falls to my colleagues to preserve what we have here on campus.” Being able to offload that responsibility to JSTOR takes a lot of work off of librarians’ plates, he noted.

Skidmore is using the preservation feature to preserve more than 300,000 digital objects across a wide range of file types, including .tif, .pdf, .wav, and more—safeguarding the long-term availability of these items.

“I can see they’re being used”

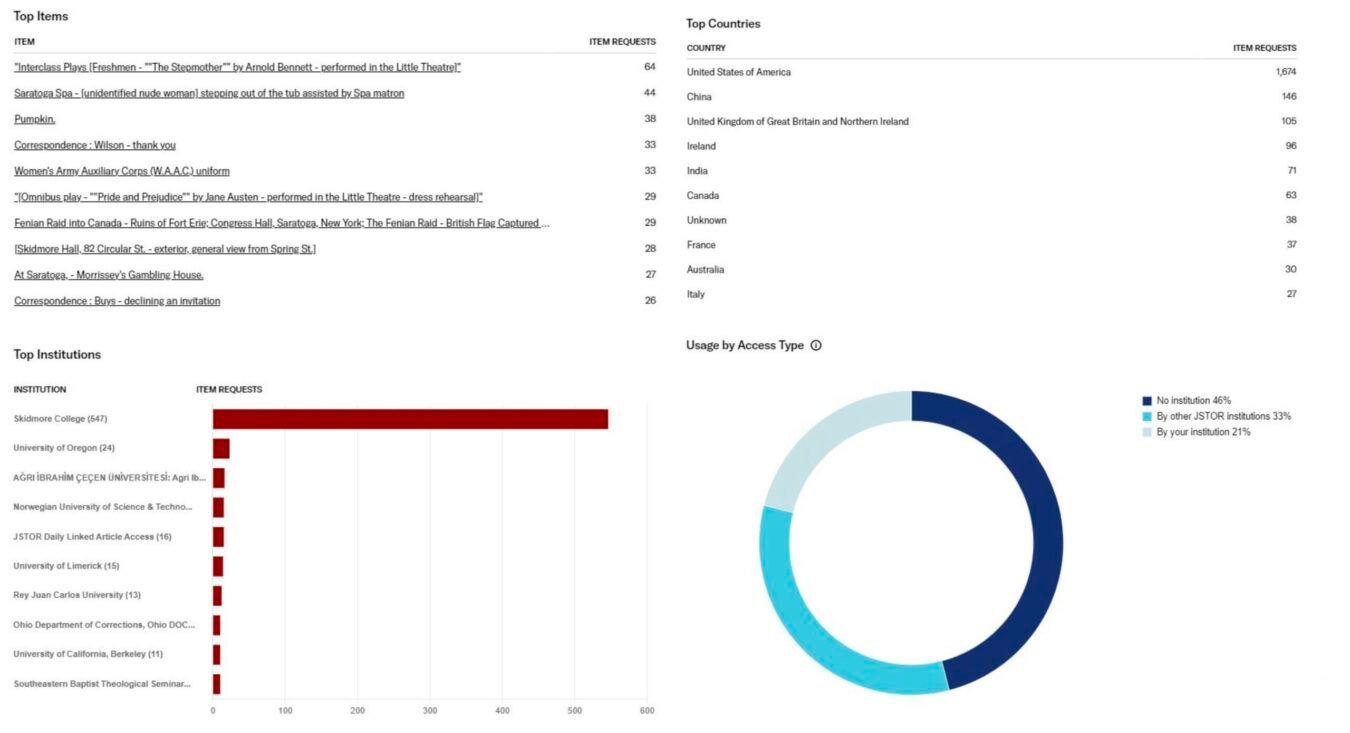

Skidmore’s usage dashboard shows how frequently their special collections are being accessed on JSTOR and by whom. Through mid-February 2025, Skidmore’s special collections on JSTOR generated usage from 93 different countries. While students and faculty at Skidmore are the biggest users, they account for only 38 percent of the collections’ total use.

“I can see that our special collections are being used,” Seiler said. “That means they’re being seen on the platform.”

Preserving digital collections for the long term and making them more easily discoverable aligns with the mission of academic libraries, he added, noting that librarians have a responsibility to disseminate their special collections as broadly as possible.

It’s about having a commitment as an institution that you’re willing to share these materials as much as you can… We’ve done the work, and we’ve seen the benefits.

Connect with our team to learn how you can streamline your digital collection workflows with JSTOR Digital Stewardship Services.

Maximize the impact of your digital collections

Join 300+ institutions partnering with JSTOR to process, manage, preserve, and share their collections with the world.