Too Fancy for Freedom:

Navigating the Bureaucratic Labyrinth of Work Release with a Degree

Navigating the path from incarceration to societal reintegration has been a journey laden with systemic barriers, designed, it seems, to test my resolve at every turn. This essay reflects on my personal experiences with these challenges, particularly focusing on my engagement with a work release program that conflictingly seemed to obstruct rather than aid my reentry. Please do not use my full name as I am still on work release, but I would like people to know how hard it can be to try to use prison education to its maximum benefit while trying to reintegrate.

Achieving a bachelor’s degree in Social Studies while incarcerated was transformative. This educational milestone enabled me to qualify for work release, allowing me the opportunity to seek meaningful employment outside the confines of prison walls. Yet, the privilege of work release came with a slew of stringent conditions that made the job search process not a test of perseverance and a Kafkaesque ordeal.

The first step in securing employment—getting fingerprinted for a background check—unveiled a series of bureaucratic barriers. The process required a state-issued ID, which I was barred from obtaining due to the restrictions of the work release program. This catch-22 situation highlighted the first of many institutional failures: I needed an ID for fingerprinting essential for employment, yet acquiring one was against the program’s rules.

Furthermore, when I was finally able to attempt the fingerprinting, the machine was malfunctioning, adding another hurdle to my already precarious situation. Each delay not only frustrated my efforts but also heightened the risk of revoking my work release, threatening to send me back to full-time incarceration.

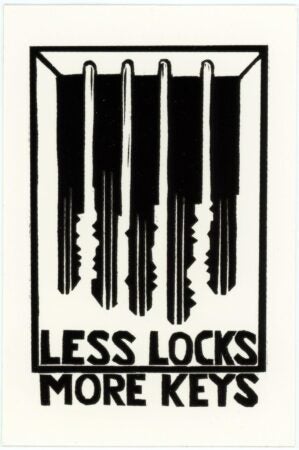

Amid these challenges, I found hope in a reentry program connected to the college I attended while in prison. This program, which offered a stipend and was framed as training rather than direct employment, seemed like a perfect bridge to use my degree meaningfully. However, the Department of Corrections, guided by a narrow interpretation of what constituted acceptable work release employment, refused to approve my participation. The Superintendent of Programs harbored a dislike for the program, perhaps because it did not lead directly to employment and was deemed too academic or ‘fancy’ for someone in my position.

The department would have readily approved a job at a fast-food restaurant, but I aspired to leverage my Social Studies degree. The pushback I received for aiming beyond menial jobs was disheartening; I was admonished for being ‘disrespectful’ and ‘fancy’ simply for advocating for a career that matched my qualifications and aspirations.

Despite these discouragements, I held out for a job that would respect my educational background and personal growth. My current job, which pays $60,000 a year, was secured thanks to the debate club and other enrichment activities provided by the college program while I was in prison. These experiences were instrumental in showcasing my capabilities beyond the typical expectations for someone in my situation.

My journey underscores the urgent need for systemic reform in how rehabilitation and reentry are facilitated. The work release program’s narrow focus on immediate, menial employment overlooks the broader rehabilitative benefits of aligning employment opportunities with an individual’s education and aspirations. True rehabilitation should be about more than just releasing individuals back into society; it should be about empowering them to use their skills and education to contribute meaningfully. My experience is a testament to the need for change that recognizes the value of education in rehabilitation and provides a genuine pathway for those transitioning out of incarceration to reintegrate as whole, valued members of society.

Editor’s Note: “Kristopher” is a pseudonym we’ve used to protect the identity of this writer since he currently is navigating the challenges of work release. Due to the sensitive nature of his experiences and the potential risk of retaliation, we have omitted certain details of his story, particularly how he navigated identification barriers which are sensitive but compelling.

Kristopher’s daily routine is a rigorous balance between work outside the prison and strict curfew requirements. I chose this essay since his experience illuminates a pivotal time – preparing for full release to parole. He has since been accepted into graduate school with support from the college reentry program. This program has been instrumental in guiding him through applications, campus visits, financial aid, and finding the job that met his standards.

Working with Kristopher meant coordinating communication during his limited phone access and waiting for email responses. His determination is evident, and we plan to share his full story, including these withheld details, under his real name once he is safely out of the system. His narrative underscores the need for holistic reentry structures that are flexible, supportive, and individualized.