Artstor has recently made available images of commercial art, canonical works, and thousands of personal Polaroids from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Artstor’s Damian Shand speaks to Michael Hermann, the Foundation’s director of licensing, about the collection.

Damian Shand: 35,000 images from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts have just been made available in the Artstor Digital Library. What were the origins of the collection and how difficult was it to bring all the material together for digitization?

Michael Hermann: When Warhol passed away in 1987, he left his extensive inventory of artwork to the Foundation. In order to get such a large, complicated collection cataloged, archived, photographed and digitized, the Foundation embarked on what turned out to be an ongoing 30-year project. The endeavor has been time-consuming and expensive, but as stewards of Warhol’s legacy, we feel it was necessary. Traditional means were used to document the collection while adapting to technological advancements where necessary. In the case of the 28,000 photographs now available on the Artstor Digital Library, we used a crowd-sourcing model. The original 28,000 Warhol photographs were donated to over 180 college and university museums and galleries who in turn documented the artworks and sent the high-resolution digital images back to us.

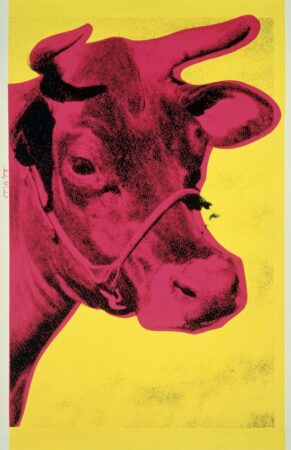

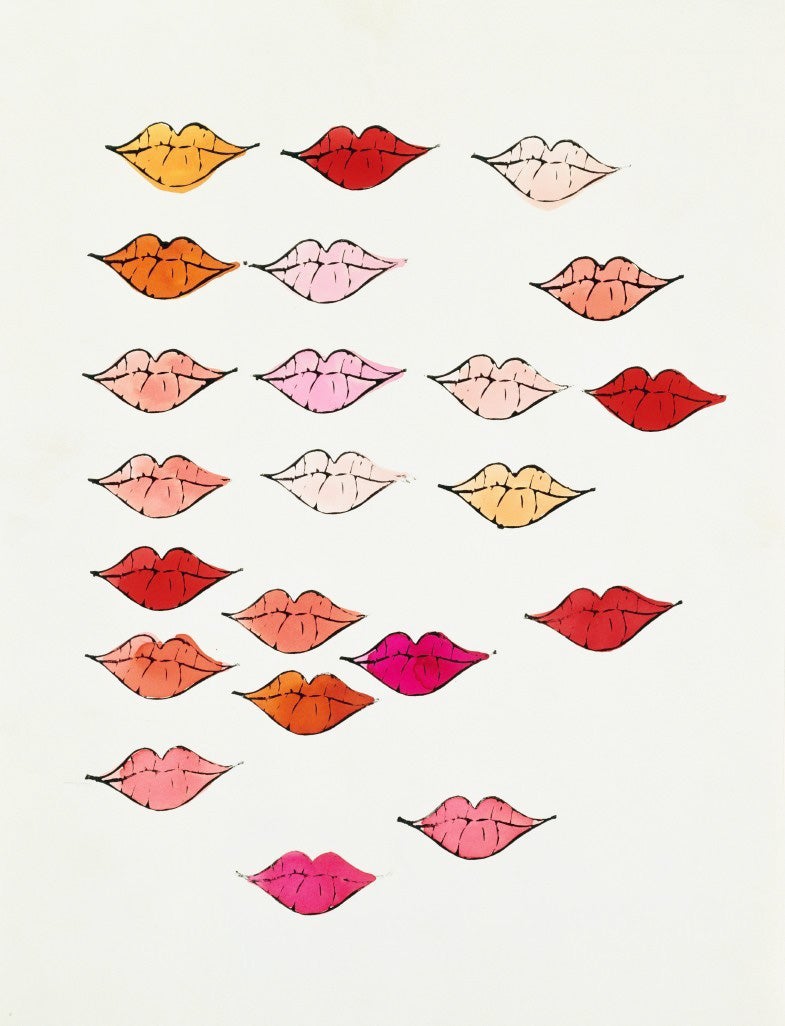

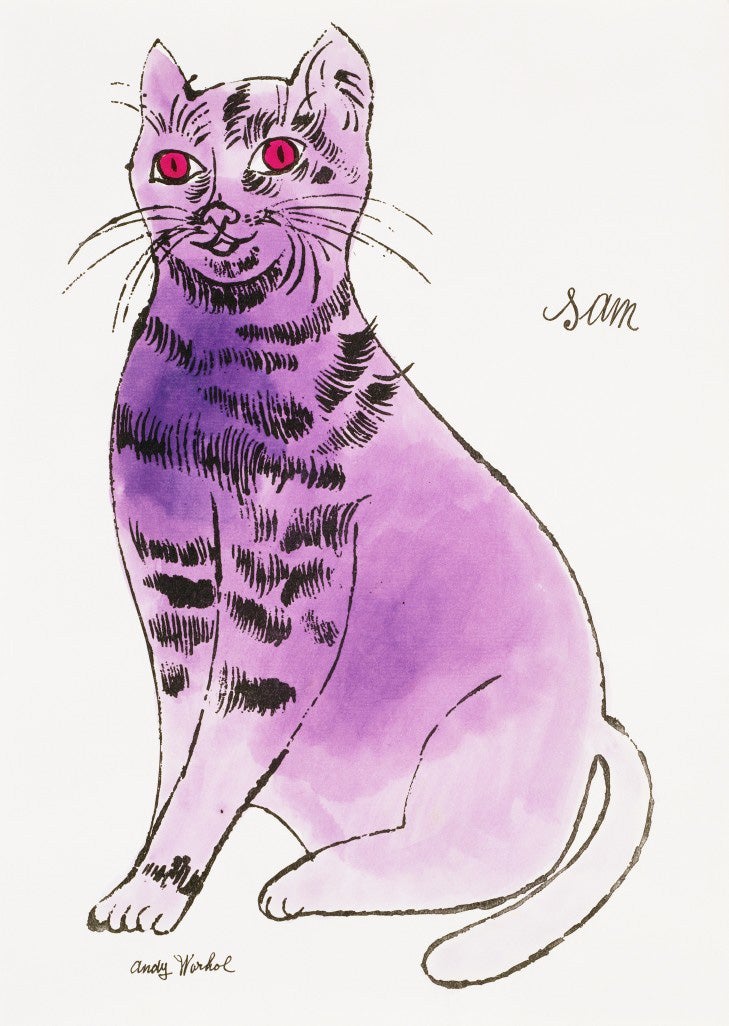

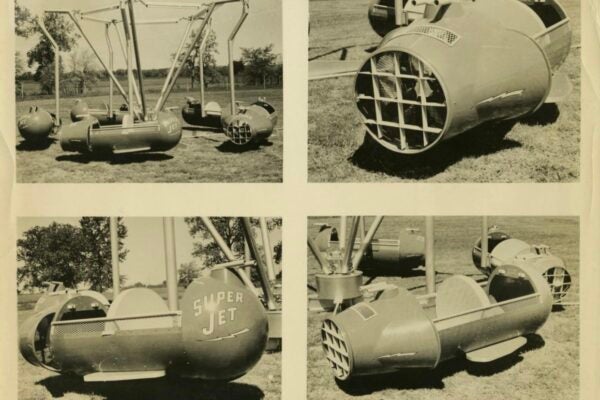

DS: The collection features some of Warhol’s early work as a commercial artist in the 1950s – how much can you see the direction of his later work in this material?

MH: I think it is certainly there in concept, if not in form. His early illustrations are whimsical, handmade, and light while his iconic silkscreens tend to be graphic and bold. Nevertheless, in both cases he leveraged a unique means to quickly create multiple reproductions, often appropriated from commonly available sources, and used assistants to help create works. In many of these early illustrations Warhol employed his blotted line technique where he would trace images in ink and then blot that wet ink onto another piece of paper – a process he could repeat over and over for the same image. He also hosted painting parties and had assistants help hand-color images. He collaborated with different writers – his mother even wrote copy for him! He became one of the most sought-after, prolific, and original commercial artists of the 1950s. In many ways, this was the Factory in embryo form.

DS: A major part of the collection consists of more than 28,000 photographs taken by Warhol, many of which document his daily life. What lay behind his obsession with recording the day to day and how do the results complement his better known, iconic work?

MH: It’s always hard to jump into somebody’s head, particularly if that person is Andy Warhol. However, when looking at these photos, it’s fairly obvious he was a voyeur and obsessive collector. In his own words, Warhol said, “A picture means I know where I was every minute. That’s why I take pictures. It’s a visual diary.” In addition to being an avid photographer, Warhol was also a writer and diarist who compulsively documented his life through film, video, and audiotapes – even referring to his tape recorder as his “wife.” From photos of celebrities to the mundane act of tape-recording an entire play he attended, what may have seemed eccentric at the time foreshadowed our world today and what many of us regularly do with our phone cameras and on social media. However, photography wasn’t just a medium he used to document his life or as source material for other works, he clearly saw his photography as works of art. In fact, one of his last exhibitions before his untimely death was of his photography – at Robert Miller Gallery in New York City.

DS: In your opinion, what are some of the individual highlights?

MH: I’m a huge fan of some of the earlier Polaroids. I think they’re quite revealing and tell the story of Andy in a number of different ways. They exhibit his great artistic eye, show the fascinating people, events, and places he encountered, but most interestingly, I feel they also humanize Warhol in a way his other work doesn’t. From loving snapshots of boyfriends to portraits of his mother at home to images of his dog Archie frolicking in the sun, we see glimpses of the person that is often obscured by his myth and celebrity.

DS: Was there something about the instant medium of Polaroid photography that appealed to him particularly?

MH: Warhol was always an early adopter of new technologies and Polaroid was no different. He began using it in the 1950s shortly after it became commercially available. Like a lot of people, he was fascinated by the immediacy of Polaroid. However, as an obsessive collector, I imagine Polaroids were particularly interesting as objects that were evidence of a passing moment. In fact, he often had his subjects sign his Polaroids after capturing their portrait as if to provide even greater evidence of his encounter with the individual.

DS: In addition to taking photos, Warhol made around 600 films and 2,500 videos, often featuring portraits of friends and visitors to the Factory, who he deemed to have “star quality.” What were the origins of Warhol’s fascination with celebrity and how did it inform his work?

MH: From a young age, Warhol was fascinated by celebrities – in fact, he wrote to them as a child to seek their autographs. He was particularly interested in someone who offered something new and unique, who didn’t have to demand attention but was able to command it. Think Edie Sedgwick, of whom he said, “Edie was incredible on camera – just the way she moved. And she never stopped moving for a second – even when she was sleeping, her hands were wide awake. She was all energy.” In many ways, Warhol’s Polaroid, photographic, and screen test portraits were an immediate way for Warhol to collect people – especially celebrities. There’s a great story about when he met the Pope in Rome. He didn’t talk about the impact of the experience but focused on his deep regret that he was unable to get a Polaroid portrait of him. It’s if having a visual record helped him share in the celebrity, with these photographic objects becoming his personal relics.

DS: Why did you decide to make your images available to Artstor users, and how does this help further the Warhol Foundation’s mission?

MH: We are delighted to work with Artstor to make an unprecedented 30,000 images of Warhol works available to its global educational community (and with no financial benefit to the Foundation). As strong advocates of freedom of expression, we are pleased to encourage new scholarly views about Warhol and his work. While our stewardship of Warhol’s legacy is an important responsibility, over the years I have come to see how prevalent his influence is in contemporary culture, recognizing that in many ways Warhol’s legacy belongs to the world. We are confident that Artstor is a diligent steward of content, balancing security and accessibility to a much larger audience than we could ever reach. It’s amazing that thirty years after his death, people are still trying to figure him out. With this extensive collection of Warhol works, the Artstor community has a great opportunity to try to do just that.

DS: If he could, what do you think Warhol would want to say to the thousands of Digital Library users around the world accessing his work and life online?

MH: Again, I don’t think I’d normally want to get into his head like this, but in this case I think he’d say something very pithy like, “Gee, this is great.”

View the Warhol’s Oeuvre and Photographic Legacy Project collections in the Artstor Digital Library.