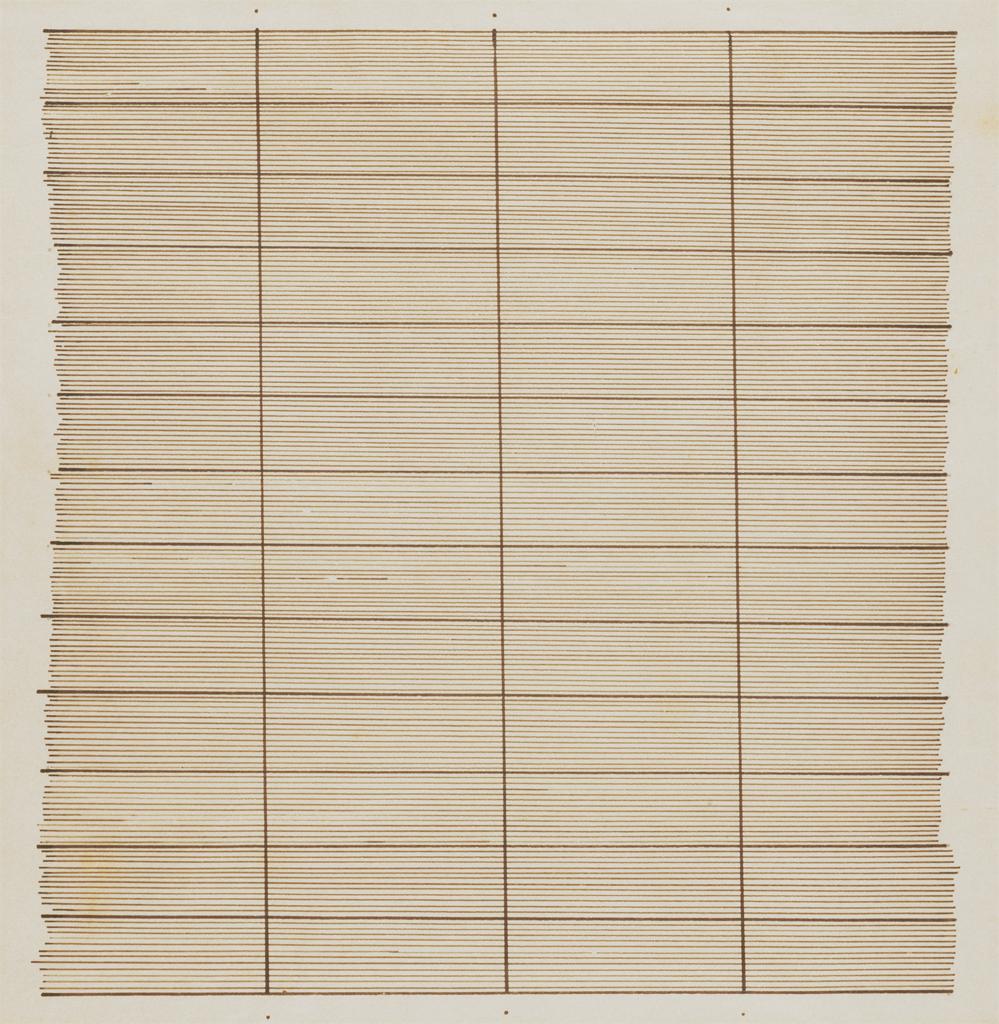

To the pioneers of Minimalism, Agnes Martin’s grid paintings were an early source of inspiration. To the Abstract Expressionists, Martin was a peer, whose use of line to cover canvases from edge to edge was not a gesture of Minimal art, but an expression of the AbEx concept of “allover” painting. In her own words, her pale, meditative geometry harkened back to much older ideas. Her art, she claimed, should be recognized alongside that of the ancient’s— the Egyptians, Greeks, Coptics, and, most importantly, Chinese.

Born in 1912 in rural Canada, and raised in the Pacific Northwest, Martin moved to New York City in 1932 to attend Teacher’s College at Columbia University for a Bachelor’s and, later, Master’s in art education. She would leave New York to teach in New Mexico soon after, only to be recalled in 1957 by the gallerist Betty Parsons, who agreed to exhibit Martin’s work on the condition that the then-unknown artist relocate.

It was during this period in New York that Martin began to develop her trademark style of uniform bands of muted color, expressed in squares and rectangles. She also got the chance to work closely with other downtown artists, in particular Ad Reinhardt, a friend who shared Martin’s interest in Eastern thought and Zen Buddhism. After Reinhardt’s death in 1967 Martin would return to New Mexico, where she remained until her own death in 2004.

While Reinhardt used Zen Buddhism to explore spatial and spiritual negation in a series of all-black ‘ultimate paintings,’ Martin would use the philosophy to abstract, reduce, and order the beauty—and sometimes ugliness (take, for example, her 1966 piece The City) —she saw in landscapes around her. Her evocative titles, including descriptors like “Tree,” “Mountain,” and “Water,” highlight Martin’s ability to tune out the noise of daily life and hone in on the underlying qualities of nature and of light. An incredible achievement given that Martin had more noise to tune out than most; the artist struggled with paranoid schizophrenia throughout her adult life.

With a new retrospective opened recently at the Tate Modern, London, and a comprehensive monograph of her work released this summer, now seems like the perfect time to celebrate Agnes Martin by looking at our selection of paintings in the Digital Library, as well as photographs of her in the studio. Zoom in on images to see the precision of her line and brush work.