Seize the season! Once again we have crossed the Thanksgiving threshold into full-blown festivities and the crescendo to the new year. In celebration of the prompt to eat, drink, and be merry, we would like to present some inspiring visions.

Let’s begin with the harvest itself, the basis of all feasts and the bountiful personification of Autumn by the Brescian Antonio Rasio, 1685-1695. In one of four allegorical paintings of the season, the whimsical poster boy for produce is nearly life size and he is composed of more than 20 edibles from mushrooms to pomegranates.

The Wedding at Cana, 1563, by Venetian painter Paolo Veronese, may be considered the exemplar of all feast paintings. With the biblical narrative and the serene countenance of Christ at center, the scene diffuses as a boisterous banquet replete with contemporary costume and custom. The composition includes about 120 figures and the canvas measures roughly 22 x 33 feet, larger than most dining rooms. It took Veronese and his assistants well over one year to complete, and the canvas weighs more than 1.5 tons — formidable loot for Napoleon’s troops to transport from Venice to Paris, where it remains to this day. The scene is alive with intrigue and anecdotes, graced by bejewelled and brocaded revelers, and, as with any good feast, canine guests, a spaniel at far left, two hounds at center, and even a tiny tabletop trespasser to the right.

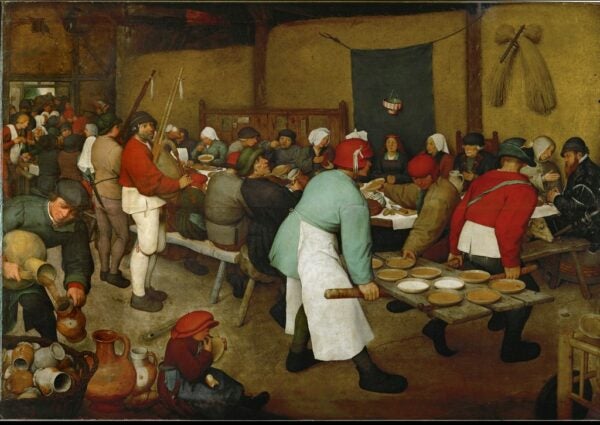

Equally famous, though far humbler in size and subject, is Pieter Bruegel’s The Elder’s Peasant Wedding, c. 1568. Exactly contemporary to Veronese’s extravaganza, the rustic Flemish festivities are earthy and homespun by comparison. Painted in oil on an oak panel, the modest details express the high art and meticulous craft of Bruegel, head of the most famous dynasty of painters in the Low Countries: servers carry bowls of porridge and/or soup on a converted door, the man in front has a wooden spoon tucked in his hat. Nearby, the requisite dog, a grizzled hound, pokes his muzzle out from under a table, sniffing crumbs on a bench.

The Feast of the Gods, c. 1618, by Hendrik van Balen and Jan Brueghel the Elder (son of Pieter), reprises the wedding banquet on a divine stage. Painted on a relatively small copper panel, the support enables meticulous brushwork and lends a fine lustrous finish. The celebrants Peleus and Thetis are seated on the far side of the table, identified by gold crowns. Dozens of deities, nymphs, and putti swirl around the table, flesh shrouded in vibrant draperies. The spread on the table, oysters and shellfish, is met with an abundance of luscious fruit spilling over the scene. The obligatory dog, Diana’s elegant greyhound at center, is accompanied by a sea monster lurking beneath the tablecloth. The adjacent trident suggests that his master Neptune is the bearded guest above him.

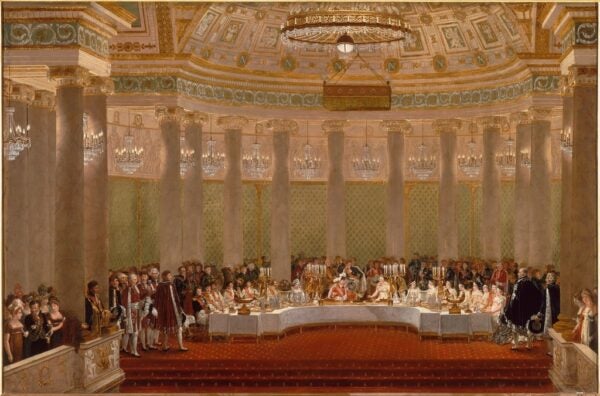

Not a canine or putto in sight at the relatively stilted Marriage Banquet of Napoleon I and Marie-Louise, 1812, by Alexandre Benoît Jean Dufay. The Emperor celebrated his second marriage in 1810 at the Tuileries, in the formal tradition of the grand couvert, where the party was observed at a horseshoe-shaped table. The meal was a cursory 20-minute affair (apparently Napoleon was no gourmand), and the food was overshadowed by the tableware, a vermeil ensemble of hundreds of pieces.

What of the pleasures of the solitary repast, as in Léon Bakst’s Supper, 1902? The Russian painter, best known for his theatrical set and costume designs, graces his table with just a few oranges and the finest flute of champagne, a feast for an aesthete.

As an admonition to overindulgence during the season, we draw to a close with an allegorical image of Gluttony, 1589, holding a pie aloft and anchored by a swine, an engraving by Jacob Matham, after Hendrick Goltzius, one of a series on the Seven Deadly Sins.

Finally, when all is said and done, the glasses are empty, the plates bare, and the candles extinguished even the detritus is captured in a cunning mosaic, a trompe l’oeil of leftovers, the Asaroton (Unswept Floor), detail, 2nd century CE by the Greek artist Herakleitos, after a painting by Sosos. The mosaic, from the floor of a triclinium, is the graphic reminder that every feast is ephemeral and that one must seize the day.

– Nancy Minty, Collections Editor

Collections

Réunion des Musées Nationaux (RMN)