Shopping paradise: Émile Zola and the world’s first department store

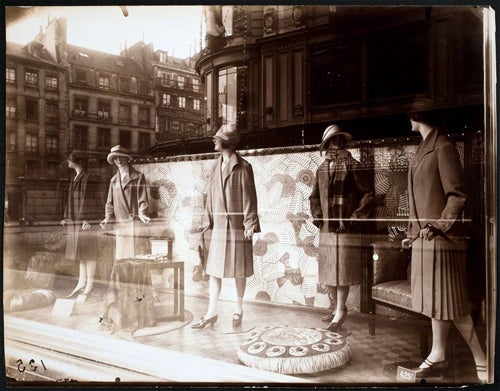

Eugène Atget, Bon Marche, 1926-27. George Eastman House

I recently came across the BBC adaptation of Émile Zola’s The Ladies’ Paradise and, as a self-confessed Francophile, couldn’t wait to begin watching it. A few episodes in, though, my enthusiasm dimmed when it became clear that the series didn’t faithfully follow the book. Zola’s novel is, at heart, an acerbic commentary on consumer culture, not a love story. Where Zola makes The Ladies’ Paradise, a department store, into a protagonist, the show instead relies on the budding romance between a shop girl and the store’s owner to drive it along. The Ladies’ Paradise is the backdrop of the story, but unfortunately not its focus.

Zola, often credited as one of the shrewdest observers of 19th-century French society, did not choose the department store arbitrarily as the setting for his novel. By the time he wrote The Ladies’ Paradise in the 1880s, the department store had become one of the most iconic features of modern Parisian life.

Gustave Eiffel; Louis Auguste Boileau, Le Bon Marché, 1876. Image and catalog data provided by Allan T. Kohl, Minneapolis College of Art and Design

The Ladies’ Paradise was modelled on a real store: the Bon Marché, which still stands today. When the Bon Marché debuted in 1852 (it was founded in 1838, but expanded to its recognizable form in 1852) the closest thing to a department store was a magasin de nouveautés, a bazaar-like shop for women’s clothing and accessories. No other stores offered a variety of goods, and clothing and accessories were usually purchased from small specialty shops dedicated to one item, like a milliner. Prices were negotiated between the seller and buyer, and clothing was custom made.

The Bon Marché is of historical import for being the world’s first department store, and for completely overturning these previous models of shopping and consumption. Unlike earlier stores, the Bon Marché sold goods for the whole family, and further, did so in a large, airy building. Eye-catching counters spread throughout encouraged patrons to walk the full length of each floor, making the store feel more like an extension of the boulevards than an interior space. (If the TV series gets anything right, it’s visual excess. By all accounts, contemporary clientele were astonished by the Bon Marché’s size and dazzling windows and displays.)

More radical than its architecture was its groundbreaking price model. The Bon Marché was one of the first places to feature mass-produced and ready-to-wear clothing, which made fashion and luxury more affordable for the emergent middle classes. The store also set fixed prices for all items, and marked them visibly on price tags—allowing shoppers to set aside anxieties over eventual haggling and concentrate on enjoying themselves.

Byron Company, R.H. Macy & Co., 34th St. & Broadway, 1913. Museum of the City of New York

As time went on, additional features and promotions were added to lure customers—especially women— into the store: from the production of a sales catalogue, to the addition of an interior cafeteria and reading room for weary husbands to wait for their retail-happy wives. (The perception of the department store as a “feminine” space is historically accurate, but only because it was one of the few spaces deemed acceptable for women to navigate without male supervision.)

Though online shopping has made the department store feel somewhat archaic, the Bon Marché vision of shopping as a mass leisure activity still, for better or worse, informs consumption and labor today. A look at some of the Artstor images of the Bon Marché, and other early examples of department stores, helps replicate wonder and shock that first-time visitors must have felt.

– Hannah Stamler