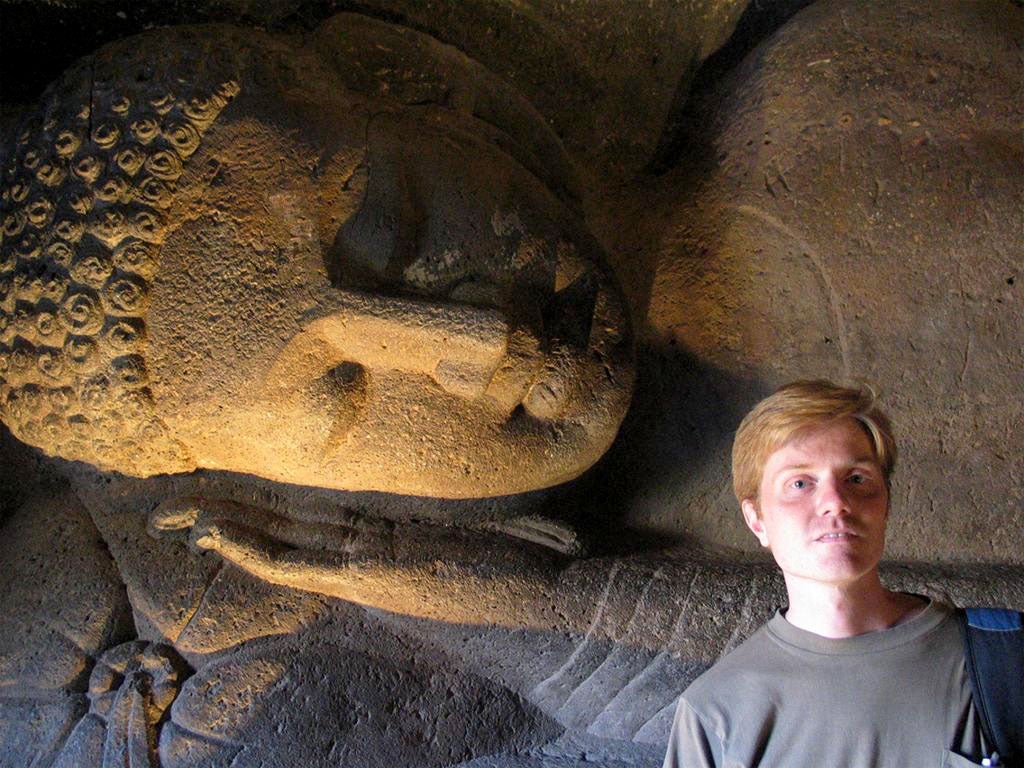

Professor David S. Efurd’s collection of nearly 10,000 photographs of Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain art and architecture was recently released in Artstor. We were particularly impressed by the variety and complexity of the rock-cut cave temples he photographed, and he was kind enough to answer our questions.

Artstor: What is the importance of caves as the sites of some of these temples, as opposed to more typical, free-standing temples?

David Efurd: Regarding Buddhist caves, monks appear to have lived in natural caves and rock-shelters since the time of the Buddha. In fact, texts describe the Buddha as spending nights in caves at a variety of locations in northeastern India. Over time, simple shelters were enlarged by cutting away stone, and masonry walls may have been added to the front to make them more architectural.

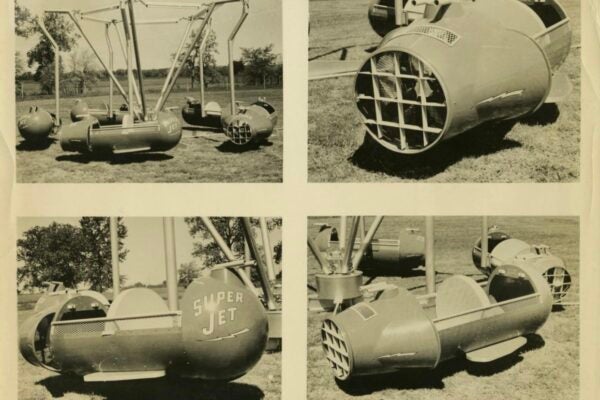

In western India, these Buddhist sites are a bit later, perhaps dating from the second century BC at the earliest. Unlike the caves the Buddha lived in, they do not appear to be natural caves that were enlarged. Rather, they were carved deeply into outcroppings of stone or cliffs and tend to be architectonic, meaning that they resemble the interior spaces of architecture, despite being hewn into stone. Few free-standing buildings and monasteries from this period survive, so these caves provide crucial insight into a tradition of architecture that has all but disappeared. Rock-cut or cave architecture from this period draws upon both this early tradition of living in natural caves and the later monastic complexes consisting of residential buildings and places for instruction and worship.

Is there a direct relationship between the Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain cave temples, or did they develop separately?

Buddhist sites are perhaps the most intriguing to me because they served as residences for the monks, in addition to locations the lay community would visit and where various rituals would take place. Although there are some Jain sites like that, many are temples, and the same is typically the case for Hindu sites. While I am sure there is some crossover in the technique of cutting caves, the interiors of the caves and the imagery one finds are quite different due to religious affiliation. I would guess that, generally speaking, the caves and cave temples for one religion resemble the built architecture of that tradition more than the caves employed by other religious groups.

Your photographs show some outstanding structures; it must be quite impressive to experience them in person. Did you encounter anything that you didn’t expect you when you visited?

One of the things I was struck by was the enormous variety of caves. There are some truly stupendous caves with beautifully carved sculptures and high-vaulted ceilings, as well as monastic residences with as many as eighteen rock-cut cells arranged around a rectangular hall. At the same site, I would find a cave consisting of a single monastic cell or a pairing of cells, or a simple rectangular hall of modest size with little or no sculptural adornment. There are different explanations for this. Patrons at Buddhist sites were rarely members of royalty; they gave what they could afford to provide for the monks. It may be a simple cave, or a component in a larger complex. While our eyes (and cameras) tend to focus on the most beautiful and spectacular caves, I soon learned that all of the caves at these sites were important to understanding how these monasteries functioned, how patronage worked, and how the caves served the monastic communities that lived there.

We were surprised by how intact the interiors and sculptures still looked – are these really preserved from the time of their creation, or were they restored at later dates?

Some are well-preserved. The caves at Ajanta, for example, were abandoned at an uncertain date in the ancient world and slowly filled up with debris and runoff from the yearly monsoon. When John Smith, a British cavalryman, explored the caves in 1819, he found Buddhist paintings still covering the interior walls! In the nineteenth century, the debris was cleared away to allow a systematic analysis of these works. Most of the paintings date to the late fifth century AD, with some examples dating even as far back as the first century BC. The murals at Ajanta are so important because they are among the earliest examples of paintings we have from Indian civilization. The remoteness of the cave site and their shelter from the elements contributed to their preservation, whereas most other paintings from this era perished.

Many cave sites have required restoration and periodic preservation efforts. The Archaeological Survey of India manages several sites I visited and maintains them.

You’ve amassed an impressive amount of images—how accessible are these sites?

They really run the gamut in their approachability. When I was in India during my Fulbright year, I endeavored to make it to as many cave sites as I could, however difficult they may have been to access. A few of the sites, such as Thanale-Nadsur and Banoti, required a jeep ride into the countryside, followed by an hour or more of hiking to reach them. Others are close to cities. Kondivte, also known as Mahakali, is in suburban Mumbai—on Mahakali Caves Road! Some, like Ajanta and Ellora, are common tourist destinations. Many others, like Khed and Pohale, are less visited. The sites cover an incredible geographical expanse, too.

There was news recently of a massive monument discovered in Petra, Jordan. Might there be cave temples in Asia that remain to be discovered, or is that region better documented?

There have been amazing discoveries at Petra, as well as in the vicinity of Angkor Vat in Cambodia. I would say that the types of caves I study are likely less well-documented, in part due to their wide geographical distribution. Even at some of the known sites, there is work to do. If you look at photographs I took at Kol, you can see caves that are still filled with debris, as if underground, with dirt almost all the way up to the ceiling. It might sound strange to many of us not from the region, but these man-made caves are an unusually common fixture in the natural landscape. Some have been appropriated by sadhus and holy men who live in them today. Others serve as temples for Hindu gods and goddesses, regardless of their original religious affiliation. Perhaps some caves are still hidden from view. While many are probably of the modest variety, I would be willing to bet there are significant architectural discoveries to be made, as well as overlooked inscriptions that will add to our understanding of ancient India and its history.

This might be a silly question since you visited so many sites, but did you have a favorite?

Field research on these caves consisted of a number of challenges, from clarifying the existence of cave sites known through conflicting names to the need to check reports of “temples” at remote locations that were possibly ancient caves. One site I visited, at Yeradvadi along the Karad-Chiplun Road, was a temple dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva. The moment I saw it I realized it had a previous career as a Buddhist cave. The excavation was once a caitya hall, an architectural form more commonly used by ancient Buddhists consisting of an apsidal hall, high vaulted ceiling, and pillars inside the cave that demarcated a central hall from an ambulatory. However, something interesting happened long after the cave was abandoned, as the interior was partially filled in with dirt and debris over several centuries. Rather than removing this debris, the local people later installed a masonry floor on top of it to create a Hindu temple. Thus, when one walks into the cave, one is actually walking into the vaulted ceiling rather than the lower floor of the cave approximately ten feet below the masonry. Truncated pillars partially submerged under the masonry and debris encircles the interior of the cave. A linga, the image used for the worship of Shiva, was installed in the back of the hall atop the masonry floor, but the original identity of the cave is unmistakable.

As it was previously unknown to me and other scholars, and never before recognized as a former Buddhist site, I published it in the journal South Asian Studies along with a few other interesting sites I visited in southern Maharashtra state. I still recall the thrill of seeing the half-submerged cave with an added frontage, as well as the peculiar feeling of walking into the vault of a caitya hall, as previously I had only seen these sorts of ceilings from a distance on the ground. Although quite altered from its original form, this caitya hall likely was carved from rock between one thousand eight hundred and two thousand years ago. Being able to share finds like this one makes field research all the more rewarding.

View the collection in JSTOR.