As AI continues to reshape the educational landscape, trust in AI-powered tools remains a crucial yet challenging issue—particularly in the humanities. How can educators foster trust in AI while ensuring that students maintain critical thinking?

Constellate recently held a successful webinar titled “Teaching Meta-Cognition with an Open-Access Large Language Model.” Led by Dr. Alexa Alice Joubin, Director of George Washington University’s Digital Humanities Institute, the webinar explored how Dr. Joubin’s open-source, open-access AI application enhances trust that leads to ethical human-AI collaboration. Her unique focus on the “trustworthy” behaviors in AI-infused communication resonated with us, as JSTOR strives for the same value between our interactive research tool and our educator users.

Following the webinar, we sat down with Dr. Joubin to discuss AI and the humanities, including how humanistic knowledge is central to understanding AI, why humanities scholars are often resistant to AI, and how AI can be used to enhance, rather than replace, critical thinking.

How humanities research informs AI literacy

AI is often marketed as a powerful and innovative technology capable of providing seamless answers to any question or prompt. But what if we viewed AI differently—not as an ultimate source of plausible answers, but as a performative and interpretive tool, much like a theatrical performance?

As a scholar of Shakespeare, Dr. Joubin points out that “Shakespeare has often been used to launch new technologies. When ChatGPT was released in 2022, its marketing strategies emphasized the AI’s ability to write poetry. In 2023, Google named its conversational AI “Bard” to advertise its creative capacities.” She draws a unique parallel between AI-generated content and theatrical soliloquies.

“Characters like Hamlet may appear to be pouring their heart out to the audience, but in reality, they have limited perspectives and share biased information. Similarly, AI-generated outputs are not neutral—they reflect patterns, biases, and probabilistic associations rather than objective facts.”

This theatrical perspective shifts how educators and students engage with AI:

- Instead of expecting factual accuracy, students should approach AI-generated text critically, much like analyzing a literary or dramatic work.

- AI, like theatre, creates “virtual worlds” that are rooted in the real but are not always factual.

- By recognizing the performative nature of AI, students can develop a healthy skepticism, treating AI as a tool for inquiry rather than an unquestionable authority.

- AI is known to hallucinate or fabricate information, but it resonates with Shakespeare’s depictions of neurodiversity, ghosts, and strange dreams. Dr. Joubin says that “through words, Shakespeare created virtual worlds. Through simulating textual patterns, AI constructs a similar type of virtuality that is partially rooted in the real world and partially in probable worlds.”

Dr. Joubin further contextualizes this perspective within the broader history of technological anxieties.

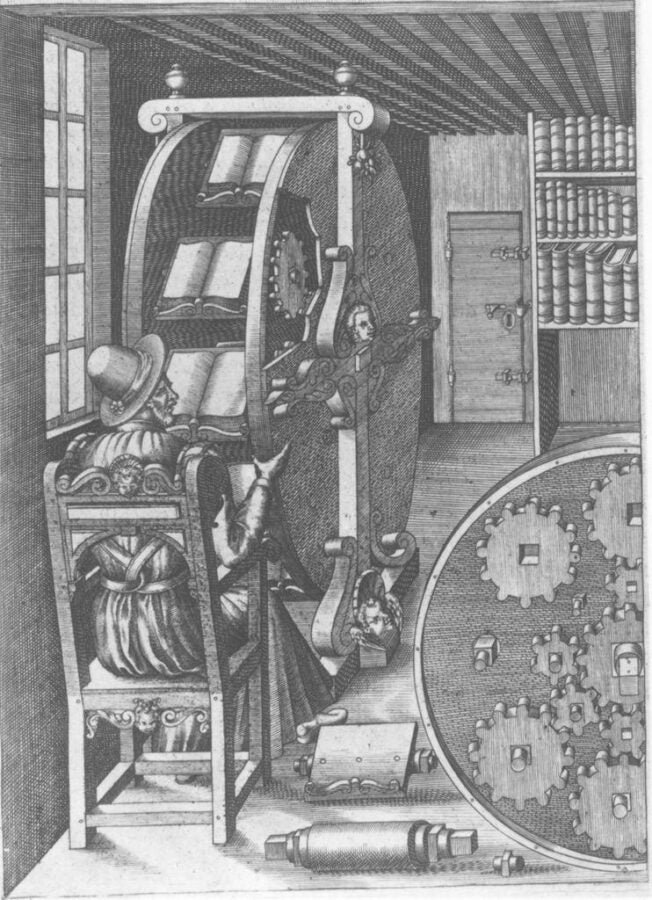

“Insights from Shakespeare and Renaissance studies also show that this is not the first time that new technologies have created anxieties and a crisis of attention. In the era of the printing press, people were unsure how to manage the deluge of printed books efficiently. The illustration shows a Renaissance-era spinning ‘book wheel’ to simultaneously read and compare multiple books. In addition to historical precedence of information management, I also realized that our contemporary tendency to anthropomorphize AI parallels Renaissance animal symbolism. Last, but not least, techné—a set of technical affordances—governs all forms of synchronous and asynchronous representational technologies. AI is a type of synchronous communication. Printed books are a type of asynchronous technology. Drawing on insights from critical AI and Shakespeare studies, I see a long and continuous history of techné, challenges, and solutions.”

One of Dr. Joubin’s insights is that “trust is not a property of an object” but rather “a type of relation and action. Trust emerges from gaining access to processes rather than merely accepting the verifiability of explicit answers.” Shifting our perspective on AI in this way helps reduce misplaced trust in AI outputs while enabling students to engage with AI as a tool for interpretation and exploration rather than passive consumption.

“The distrust results from outsourcing trust to big tech companies as gatekeepers and a lack of access to open-access, public interest technology for effective communication.”

Why are humanities scholars the most resistant to AI?

Despite the potential of AI in education, humanities scholars are among the most resistant to its adoption. According to a recent Ithaka S+R report on AI and postsecondary instructional practices, humanities educators express significant distrust in AI, particularly due to concerns about

- bias and misinformation in AI-generated content,

- erosion of critical thinking skills among students, and

- ethical concerns regarding data privacy and AI’s role in academic integrity.

Dr. Joubin attributes much of this skepticism to the fact that AI tools are often controlled by big tech companies with opaque processes.

“The distrust results from outsourcing trust to big tech companies as gatekeepers and a lack of access to open-access, public interest technology for effective communication. Effective communication requires empathy and critical thinking to navigate diverse perspectives and foster relational understanding—skills essential for academic and career success. Yet, a lack of trust-engendering infrastructure hinders such skill development, leaving individuals reliant on non-participatory, commercial tools. This highlights the urgent need for an infrastructure for empathetic communication.”

To address this distrust, she advocates for open-source and open-access AI models that allow educators to

- customize AI tools to fit specific academic needs,

- retain control over training data and algorithmic decision-making, and

- ensure transparency in how AI processes information.

By shifting AI development into the hands of educators, institutions can build AI systems that align with academic values rather than corporate interests. In building this infrastructure, Dr. Joubin emphasizes “participatory design principles” that prioritize “the interest of users who have been excluded from participatory justice.”

AI should be an augmentation tool and “social technology,” not a replacement for critical engagement.

Can AI enhance critical thinking, instead of undermining it?

A common fear among educators is that AI will weaken students’ critical thinking skills by encouraging passive consumption of generated content. However, Dr. Joubin has designed assignments that use AI to enhance students’ metacognitive skills; that is, to help students think about their own thinking, rather than replace critical thinking. Using her open-access AI, she incorporates AI into responsive pedagogy, where students

- use AI to explore multiple perspectives on a given topic,

- engage in role-playing exercises where AI simulates different viewpoints, and

- use AI to detect patterns in student writing.

“For example, instead of asking AI for a definitive meaning of a play by Shakespeare, students use my course resident AI (as an imperfect synthesis of anonymized public voices) to examine possible reactions to a scene. Students would share with AI their thoughts on a particular scene, drawing on their personal experiences. They then ask the AI to offer other historical and contemporary perspectives on the scene to broaden their horizon beyond their age group and their own backgrounds. They also ask AI to role play and simulate reactions from various communities. The role-playing function is enabled by my background scaffolding documents as training dataset.”

In this way, Dr. Joubin’s AI application in the classroom exemplifies how educators can design assignments to actively develop students’ metacognitive skills with AI. Such an interactive approach fosters deeper engagement by encouraging students to question, challenge, and refine their understanding rather than passively accepting AI outputs.

The key takeaway? AI should be an augmentation tool and “social technology,” not a replacement for critical engagement.

Bridging the gap: Humanities-educator collaboration with engineers

For educators interested in developing AI-powered tools for their own campuses, Dr. Joubin’s experience collaborating with engineers offers valuable insights. She emphasizes that trust in AI is not just a technical issue—it’s also a relational one: “Trust isn’t just about explainability or interpretability of a model. It’s about fostering deep social connections—between educators, students, and AI developers.”

Her four pillars of human-centered AI trust include:

- Ethics of Care – AI should serve educational values, not just efficiency

- Deep Social Connections – Collaboration between faculty, students, and developers is essential

- Beyond Verifiable Answers – AI should encourage exploration over definitive solutions

- Participatory Justice – Educators and students should have a say in AI development

By working directly with engineers, she and her team developed a participatory AI model that reflects the needs of real educators and students—not just tech companies.

For faculty considering similar projects, her advice is clear:

- Advocate for open-access AI models that prioritize academic freedom.

- Engage in cross-disciplinary collaborations between the humanities and computer science.

- Ensure that AI development remains inclusive and participatory.

Final thoughts: Building a trustworthy AI future in education

As AI continues to shape learning environments, educators must actively engage with these tools to build trust, transparency, and ethical AI practices. Dr. Joubin’s work demonstrates that AI can be integrated into humanities education without sacrificing critical thinking or academic integrity.

- By viewing AI through a humanities lens, we can approach it as a tool for interpretation rather than unquestioned authority.

- By advocating for open-access AI, we can shift power away from commercial interests and ensure that AI serves educational values.

- By fostering metacognition, we can use AI to enhance, rather than hinder, critical thinking.

For educators looking to explore ethical, transparent AI integration, Dr. Joubin’s open-access AI project offers a compelling model and makes a strong case about how educators establish trust with AI technologies in the classroom.

Additional Resources

Learn more about Dr. Joubin’s open-access textbook powered by AI, Introduction to Critical Theory.