By Joseph Costello, Medical Librarian, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine

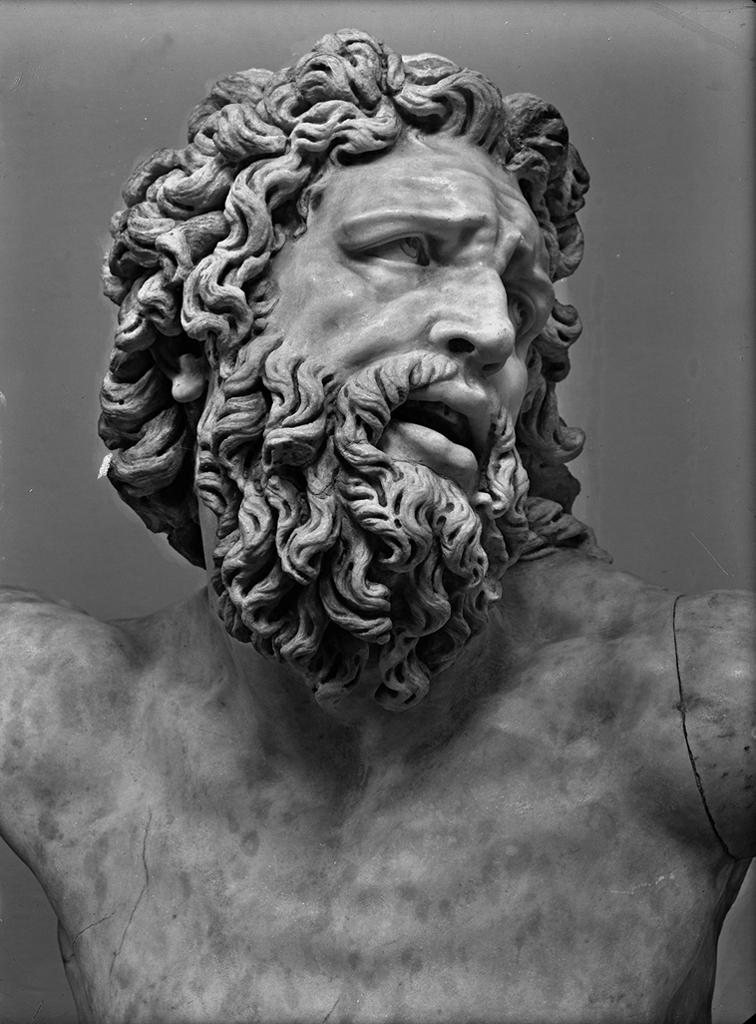

Prompt: Imagine the human expression of anguish. An amalgamation of stories, artwork, and social interactions blend together and you have your general concept of the human expression: anguish. The concept of anguish is correct to you since it is, after all, your portrayal; the anguish concept is a component in the overall conceptual framework you have constructed to assess emotional expressions. How accurate are you? In other words, how accurate are your visual detection skills of anguish or other emotions, how generalizable?

Accurate interpretation of facial expressions—the aggregate of minute facial movements we make, i.e. micro expressions—is believed to be associated with increased emotional intelligence. Researchers have shown that facial expressions can be generalized and successfully be a part of empathy training. Similarly, modern medicine generalizes the human body to find the distribution of values which in turn help generate a normal range.

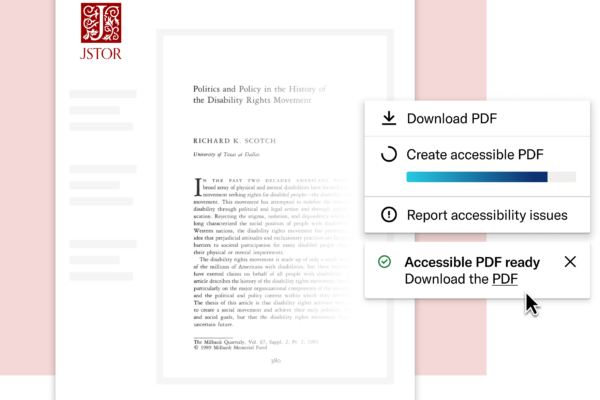

Arthur Frank mentions in The Wounded Storyteller a reflexivity in post-modern medicine that arises from generalizations of the human; a push-back from patients to restore their voice in medicine. Entering too is the Information Age, where we find ubiquitous computing—abounding online medical literature (of varying quality!) changes the landscape for physician-patient interactions. Physicians have mentioned numerous times during my career in medical libraries that current patient populations are now more than ever questioning physician decision-making.

We strongly urge all medical educators to ensure the humanities are integrated to comprehensive medical curricula. For several years now, narrative medicine has been gaining attention. For example, Rita Charon, Founder of the Narrative Medicine program at Columbia University, penned a heavily cited article in JAMA back in 2001. Charon’s article reminds us of the burden physicians may carry via vicarious trauma—a secondary trauma that occurs when we essentially “download” another’s difficult experience into our conscious experience. Diseases can be devastating for patients and families alike, so physicians can also be affected.

What can quickly be missed, or, entirely overlooked, are patient and physician narratives. The generalization of patients as bodies may undermine interpretation of any critical information a patient narrative holds. A physician may harbor residual trauma from difficult patient interactions. Generalization of the human body advances our science, to an extent; however, there may be physiological conditions which manifest simply due to a patient’s psychological maladies. A physician may face challenges with coping, and this may undermine their well-being. The question becomes one of balance: how do we train future physicians to be cognizant and keenly aware of any code words a patient may be using to articulate their experiences alongside critical quantitative information they’re learning?

After considering all the above, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine in Kalamazoo has a newly formed elective, Doctor and Patient: Gathering the Whole Story, which aims to enhance medical students’ empathy and communication skills by utilizing skills-based study of art. On day one of the course, students are asked to evaluate generalized human expressions of various emotions, to observe a work of art, and write one page on their impressions. Self-reflection after observing artwork enhances one’s ability to process subjective experiences. From there, the course delves further into art in order to enhance medical students’ visual and emotional acumen. A primary objective is physician-patient attunement which may usher new milestones in physician and patient communications.

The idea is that if we can enhance our ability to assess how art affects us, we can similarly apply these techniques to how emotional elements of human interaction leave residual impressions, i.e. enhance our coping. Understanding how difficult interactions affect us—a profound skill for early career physicians to develop—is pivotal to reinforcing resiliency while enhancing empathy. As patients become empowered and enamored with medical information they attach their story to their charts, sometimes to the chagrin of the physician who has the training and education but is being increasingly challenged in clinical settings. We want to help moderate the conversation a bit, indirectly, by using art as an “usher” to the emotional elements at play in our daily lives.