When we think about art historical research and teaching, individual artworks often take center stage. But what about the curated exhibitions that shape how we encounter and interpret them? Exhibition photography bridges this gap, capturing not only artworks but also the physical and contextual elements that define their presentation.

At the 2025 College Art Association (CAA) conference, I had the pleasure of organizing and moderating Beyond Utility: Rethinking the Value of Exhibition Photos in Art Historical Research and Curation, a panel discussion exploring the evolving role of exhibition photography. We considered how both historical and contemporary exhibition documentation can transform research, approaches to digital preservation, and curatorial practice.

The conversation brought together archivists, educators, and librarians from the Bard Graduate Center, The Museum of Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The New Museum of Contemporary Art, and Yale University Libraries, each offering unique insights into why these images—many of which are now available on Artstor on JSTOR—are an essential yet often overlooked resource for teaching and scholarship.

Beyond documentation: The research potential of exhibition photography

Michael Satalof, Archivist & Digital Preservation Specialist at Bard Graduate Center (BGC), opened the discussion by highlighting how installation photographs reflect scholarship, capturing the interplay between teaching, exhibitions, and research.

At BGC, exhibitions often emerge from faculty research and feature objects on short-term loan from private collections and museums. As a non-collecting institution, documenting these exhibitions is critical to preserving and extending their impact.

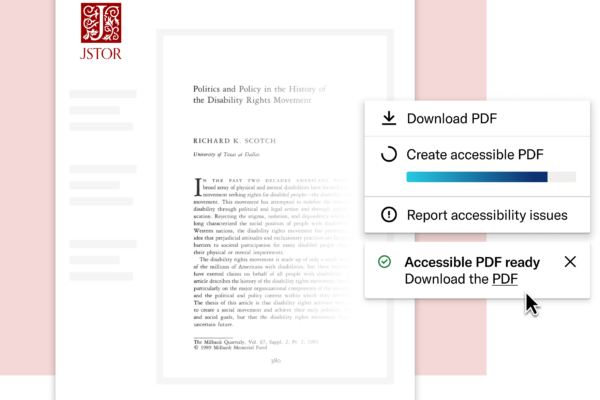

Historically, BGC’s exhibition images were stored as 35mm slides, accessible only via light tables or slide carousels. But improvements in digital photography have made it possible to capture and observe subtle curatorial choices—from lighting decisions to spatial relationships between objects. Satalof noted that interactive tools on JSTOR, including a IIIF viewer that enables scholars to zoom in and compare images side by side, have helped transform these once-static records into dynamic resources.

The value of high-resolution exhibition photography became particularly evident in March 2020, when COVID-19 forced BGC’s Eileen Gray exhibition to close just ten days after opening. Curators turned to installation images to create an interactive digital experience, ensuring continued engagement despite physical inaccessibility. As Satalof puts it, photographs “bridge the distance between the temporary ‘during’ phase and the lasting ‘after’ phase” of exhibitions, extending their scholarly utility far beyond their physical and temporal bounds.

Digitization, access, and institutional archives

Ana Marie, Archivist at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), provided a behind-the-scenes look at how museum archives decide what gets digitized. MoMA’s MAID (maid.moma.org) database houses born-digital images of recent exhibitions, while older materials—including the black-and-white installation shots taken until 2000—are largely digitized in response to researcher requests, staff needs, and preservation priorities.

Marie emphasized that digitization is largely research-driven. One example came from a request regarding work by Félix González-Torres, which included both gallery and outdoor installations. Originally, MoMA’s official installation records only included images of the gallery space, but a curator’s inquiry led to the digitization of previously overlooked photographs of its outdoor presentations—providing a fuller understanding of the artist’s intent.

Another reason MoMA prioritizes digitization? Preservation of fragile materials. Glass lantern slides, small-scale photographic prints, and other delicate archival records degrade with repeated handling. Digitization increases access while reducing physical wear, ensuring these images remain usable for future scholarship. But these projects are resource-intensive, and most large-scale efforts—like MoMA’s collaboration with Artstor to digitize exhibition photos—have been made possible through grant funding.

Detective work in the archives: Uncovering institutional histories

Stephanie Post, Senior Digital Asset Specialist at The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) explored how exhibition photographs reveal hidden aspects of institutional history.

Post shared a fascinating case of archival detective work that started with an inquiry about an Adolph Gottlieb painting. While searching for documentation, she uncovered previously undigitized exhibition images from the 1960s, which not only clarified how the painting had originally been displayed but also revealed something unexpected: historical parquet floors that had since been carpeted.

This discovery informed a recent gallery renovation, demonstrating how installation images can function as architectural and design records, not just curatorial ones. Another example? Exhibition photos confirmed that smoking was once permitted throughout The Met—not just in designated lounges, but in restaurants, events, and even galleries. These photographs now serve as visual evidence of shifting institutional norms and conservation practices over time.

Exhibition as Social Experience: Rethinking the “Empty Gallery” Shot

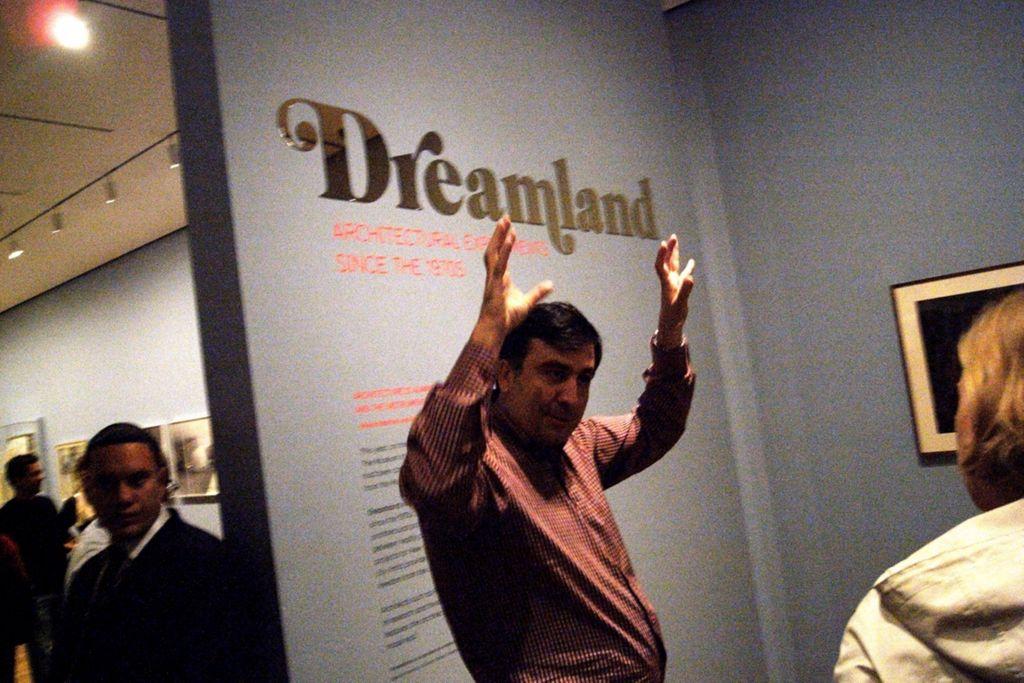

The New Museum’s Keith Haring Director of Education and Public Engagement, Alethea Rockwell underscored the importance of “how The New Museum documents, contextualizes, and teaches about our exhibition history exhibition photography” as a non-collecting museum, while simultaneously challenging the standard approach to exhibition photography—what art historian Mary Anne Staniszewski once described as “empty, idealized, and uncluttered.”

Rockwell noted that, while typical exhibition shots capture a space devoid of people, some New Museum exhibitions actively resist traditional documentation insofar as they’re inherently participatory, immersive, or populated. Bob Flanagan’s Visiting Hours, for example, placed the artist himself in a hospital bed within the gallery, where visitors could interact with him. Without images capturing this engagement, much of the work’s meaning would be lost. Other examples include Atsushi Nishijima’s Mondrian Ping Pong, which turned the museum’s storefront window into an interactive ping-pong game, and Hélio Oiticica’s Quasi-cinemas, which invited visitors to experience films from hammocks rather than traditional cinema seating.

During and after the COVID-19 pandemic, these questions became even more significant. Starting during the 2020 lockdown and through the present, the New Museum has hosted virtual exhibition walkthroughs—not as mere substitutes for in-person experiences, but as spaces for critical conversations and increased accessibility for disabled and immunocompromised audiences.

Teaching and research: Exhibition photos as visual literacy tools

Tess Colwell, Arts Librarian for Research Services at Yale, reflected on the role of exhibition photography in visual literacy, archival studies, and digital research tools.

At Yale, the shift from slide-based teaching collections to digital resources mirrors broader changes in how students and faculty engage with historical visual material. However, these legacy collections remain valuable historical records. Colwell encourages students to think critically about how exhibition photographs shape our understanding of art—through curatorial choices, institutional priorities, and even the angles chosen by photographers.

She also posed larger questions: What can we learn from these historical collections? How do exhibition photos shape our understanding of curatorial decisions, artistic narratives, and institutional priorities over time? For Colwell, exhibition photography is not just documentation—it is a resource for critical engagement, teaching, and reinterpretation.

What’s next? Keeping exhibition photography in the conversation

As active practitioners in the field, each presenter shared their own unique perspective, “shining a light on the work that goes into stewarding and activating knowledge through managing image archives, public engagement, and visual literacy instruction,” as noted by Satalof. This diversity of thought was also evident in the discussion, where “the conversation provided insight into how conference attendees, many in different roles than us, use exhibition photographs in their own work.” Yet, despite these nuances in perspective, a clear consensus emerged: exhibition photographs are not just documentation, but vital tools for research, teaching, and historical inquiry.

For those working with Artstor on JSTOR, this is an opportunity to explore how these resources can support faculty, students, and researchers alike. Exhibition photography can serve as a primary source, a pedagogical tool, and a way to rethink how art is encountered over time.

With new collections continuing to be digitized, the question isn’t just how we document exhibitions, but how we use images to expand art historical research in meaningful ways, and whose images are reflected in our corpus. Does your institution document exhibitions with hi-res installation digital photography? Please reach out to us to explore a potential partnership by contributing your digital media to our resource.