In in the vast, global virtual museum of the Artstor Digital Library, women are rising to the top. Our recent use statistics reveal that portraits and likenesses of the fairer sex (your interpretation…) dominate. The subject of women prevailed among the top 20 hits, with, you guessed it, Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, c. 1505, his serene queen, as number one (more than 12,000 views), followed closely by the Venus of Willendorf, c. 30,000-25,000 B.C.E., and Manet’s Olympia, 1863, each a distinctive icon of a particular era.

Among our fine and plentiful selections from the Berlin State Museums (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin), Warhol’s silkscreens of Marilyn, 1967, arguably the modern Mona Lisa, topped the charts, prevailing over favorites by Pieter Bruegel I, Caspar David Friedrich, Jan van Eyck and Hans Holbein the Younger. At MoMA, another version, the Gold Marilyn Monroe, 1962, figured among the top ten, and its shimmering ground recalls so many Byzantine and early Italian Madonnas, like Giotto’s Ognissanti Madonna, c. 1310, one of the most frequented images across all of our collections.

While the preponderance of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, nearly holy in its sublime equanimity, comes as no surprise, neither does the prevalence of depictions of Mary – typically titled Virgin or Madonna. Among the 1,000 most viewed images in the Artstor Digital Library, she accounts for about 5%, while depictions of Christ are about half that. Raphael’s Small Cowper Madonna, 1505, among the pervasive hits from the National Gallery of Art, epitomizes the immaculate characterization of the holy mother.

The profane state of motherhood is a common theme in favored imagery. Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s Queen Marie-Antoinette and her Children, 1787, a traditional albeit grandiose characterization, is a preferred image across collections. From the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a distinguished and refined Benin ivory, the Queen Mother Pendant Mask: Iyoba, 16th century, depicts the matrilineal source of a long-standing dynasty of the Edo people. Her image is highly sought in a collection of superstars. By contrast, Dorothea Lange’s affecting Migrant Mother, 1936, a specter of the Great Depression, is among the heavily trafficked photographs in the Artstor Digital Library. Motherhood takes on a different guise entirely in Louise Bourgeois’ Maman, 1999 (cast 2001), a most viewed work from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. The mother here is a giant spider–not a woman, but a symbol of motherhood for the artist: “The friend (the spider – why the spider?) because my best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and as useful as a spider. She could also defend herself, and me…” [1]

Intimate, domestic depictions of women from northern Europe also represent a high percentage of our chosen images. Jan Vermeer’s still interiors featuring women in quiet pursuits, such as his Woman Reading a Letter, c. 1662-1663, number three of the top five images from the Rijksmuseum (it must be said here that Rembrandt’s Night Watch is number one). Similarly, although Vermeer’s extant paintings, nearly all of women, are fewer than 40, they are consistently among the most heavily viewed works in the Digital Library. At the Frick Collection, Ingres’ Comtesse d’Haussonville, 1845, is a French Neoclassical response to the Vermeer esthetic, and Gerhard Richter’s Lesende (Reading), 1994, from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, brings it into the contemporary sphere. Both works are top hits in their respective collections.

Renderings of queens and rulers also figure in our virtual pantheon of iconic women. Images of Hatshepsut of Egypt are highly searched, as are the views of her extensive mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. The Met’s monumental limestone of Hatshepsut, c. 1473-1458 B.C.E., dressed as pharaoh, is among our most selected works from their collection. In an imposing full-length portrait from another era, Antony van Dyck portrays an English monarch with lavish trappings in Queen Henrietta Maria, 1633, an image from The National Gallery, London that figures prominently in our statistics. Velazquez’s Las Meninas, 1656, beloved at the Prado and across all Artstor collections, is a royal family portrait centering on the sparkling figure of the Infanta, the child who would become the Holy Roman Empress.

Finally, we must consider the many, many popular images in our collections that present the female form in various states of undress. Whether we call her Venus, Aphrodite, Danae, Olympia, or Odalisque, or – from the Bible – Eve, Bathsheba, Susanna, Judith, or Salome, the nude proliferates among image choices from pre-history to the present. In addition to the above-mentioned Venus of Willendorf and Manet’s Olympia, the most requested images include Manet’s Déjeuner Sur l’Herbe, 1863, Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, c. 1482, Titian’s Venus of Urbino, 1538, and Ingres’ Grande Odalisque, 1814. Virtually all of these works have been crafted by male artists (with a handful of exceptions, led by the female Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi) for male patrons – hence the undeniable role of the male gaze. Nonetheless, from antiquity on, these same artists were also turning out male nudes. Classical statuary is replete with masculine bodies, most Eves have an Adam, Davids keep pace with Venus, etc.

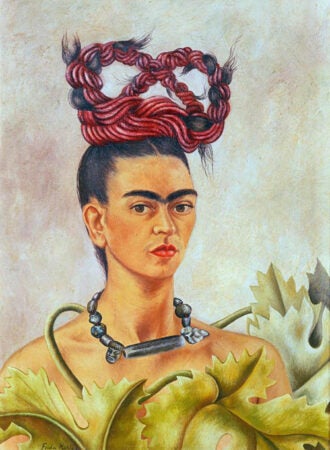

A word, at last, about the female artist – a topic deserving of a separate study. She is making progress in our statistics, but just as the Guerilla Girls protested about 25 years ago, a likeness of a naked woman is much more common in our museums than a painting by a woman, a regrettable truth reiterated above.[2] The artists most commonly searched in Artstor remain overwhelmingly male, with the following expected names vying for dominance: Picasso, van Gogh, Monet, Matisse, Warhol, Rembrandt, Caravaggio, Dali, Leonardo, and Michelangelo. Nonetheless, the occurrences of female artists are rising, most recently Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, Cindy Sherman, Mary Cassatt, Kara Walker, and Barbara Kruger.

As we reflect on these findings, we may all look forward to 2017 when more women artists will move up the list. Here at Artstor, we are also excited about the prospect of presenting new collections throughout the year, beginning with some highlights to enhance the winter months.

– Nancy Minty, Collections Editor

Check out our image group with all the discussed images and more in the Artstor Teaching Resources.

Related:

“Women’s Studies” image group in the Artstor Digital Library

Kristeva, Julia, and Jeanine Herman. “From Madonnas to Nudes: A Representation of Female Beauty.” In Hatred and Forgiveness, 57-78. Columbia University Press, 2010.