William Blake is perhaps the most famous artist born out of the British Romantic period, mostly known for his writing, paintings, and printmaking. But much like Vincent Van Gogh and Henry Darger after him, Blake was largely unrecognized during his lifetime and was mostly seen by the art community as an amateur. And while his published poetry and his illustrations of those poems are wholly original works, Blake spent the majority of his career drawing and painting scenes from fictional stories written by other authors—such as Shakespeare, Milton, Chaucer, and Dante.

In fact, it might be said that Blake spent a lot of his time working on what we now call “fan art.”

Fan art is a close cousin to “illustration,” the key difference being that fan art is mostly produced by amateur artists for personal reasons. Today you won’t find “fan art” in many art galleries. Instead, you’ll find it being crafted in parents’ basements and sold on side streets. The biggest hub for it is the internet—on websites like DeviantArt, Reddit, Etsy, and Tumblr, and in memes and gifs shared casually on Facebook and Twitter. It’s usually a labor of love without much monetary gain.

But in William Blake’s day, subject drawings and illustrations of fictional works were often more respected, sometimes commissioned, and could even help catapult an artist into the history books.

From a young age, Blake was subject to intense spiritual “visions,” and was deeply religious and reverent of the Bible throughout his life. At 16, his first original engraving, “Joseph of Arimathea Among the Rocks of Albion,” was biblically inspired, and his ink studies of The Book of Job date back to as early as 1786, when he was 29 (Blake would complete his illustrations of The Book of Job much later, in 1806, at the request of his patron Thomas Butts). Many of his biblical illustrations have affinities with traditional fan art due to his lifelong fascination with the Bible, and his drive to give visual life to its stories and characters for others.

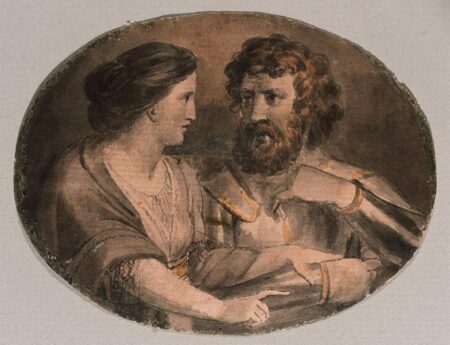

The same goes for Blake’s illustrations of Shakespeare. One of Blake’s best-known illustrations is “Pity,” which was not commissioned and was inspired by a famous line from Macbeth: “And pity, like a naked new-born babe, / Striding the blast, or heaven’s cherubim, hors’d, / Upon the sightless couriers of the air.” A little-known fact, though, is that Blake had drawn characters from Shakespeare’s plays when he was a young man. Around 1780, Blake painted a series of Shakespearian character studies that include Othello, Desdemona, Juliet, King Lear, Cordelia, Macbeth, and Lady Macbeth.

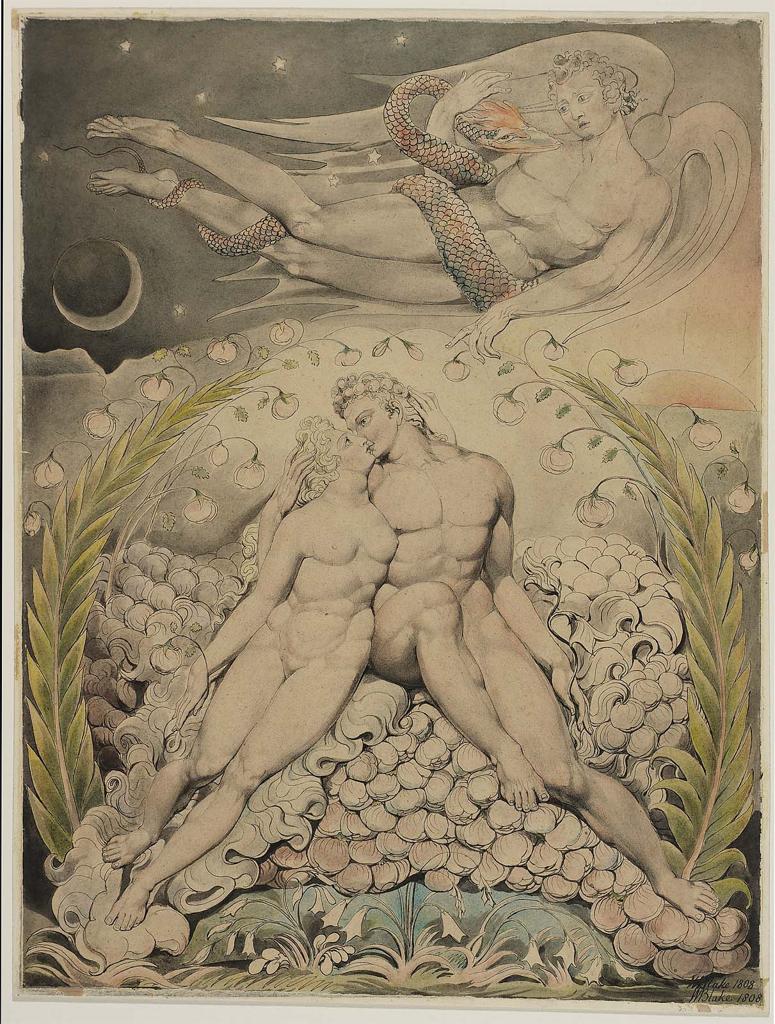

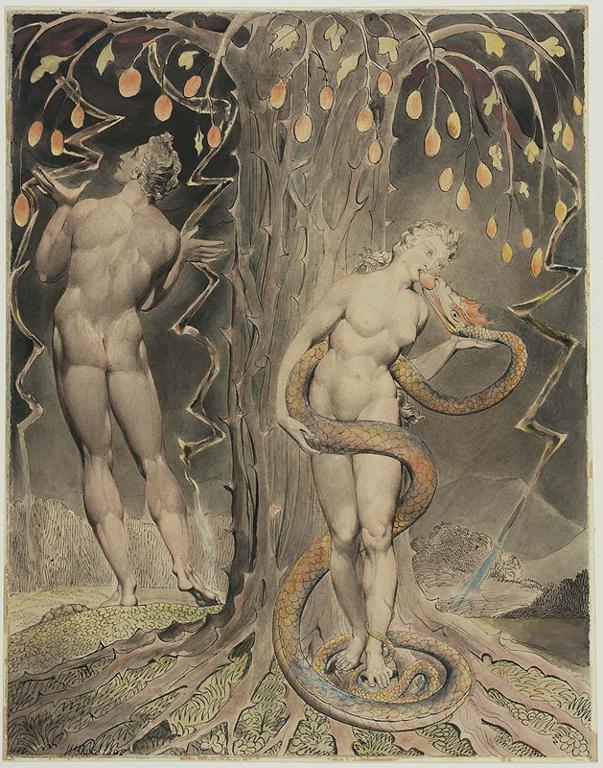

Even Blake’s more professional illustrations have a deeply personal nature to them. When asked to illustrate scenes from Milton’s Paradise Lost, Blake made it his own. He felt Milton had made the character of Satan too interesting in Books I and II and sought to correct these “faults.”

In 1804, Blake decided to illustrate characters from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. He pitched the idea to art dealer Robert Cromek, but Cromek deemed Blake too “eccentric” for his taste and commissioned Thomas Stothard instead. Blake, enraged, ended his friendship with both Cromek and Stothard and set up his own, self-financed exhibition at his brother’s shop. Unfortunately, the show received only a single review from The Examiner, and it was a hostile one.

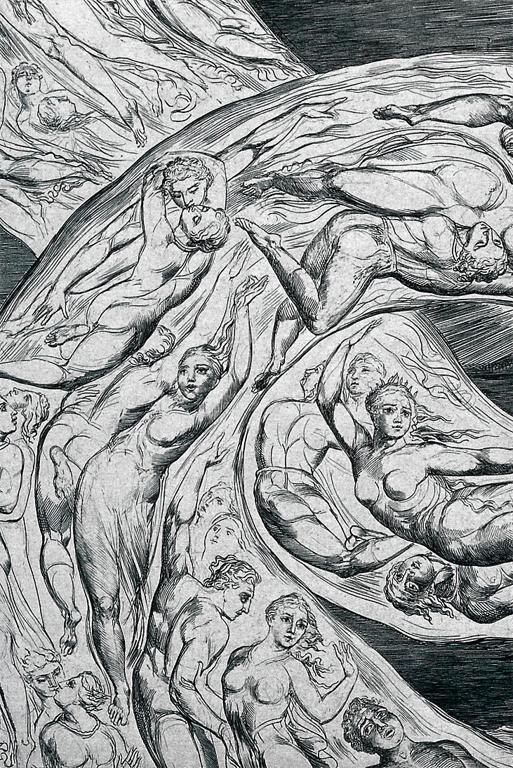

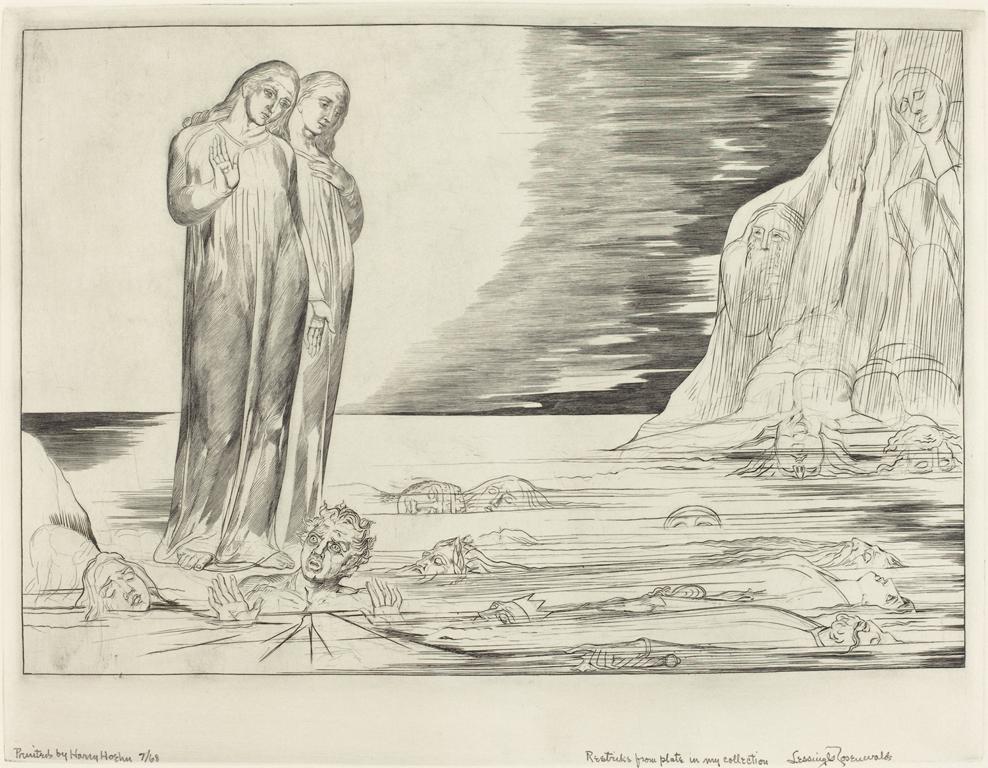

Nevertheless, Blake continued producing illustrations and fan art as his name became more recognized over the years. Toward the end of his life, he was commissioned by John Linnell to illustrate Dante’s Divine Comedy, which he worked on feverishly, starting in 1826, just one year before his death at the age of 70. The series was ultimately left unfinished. Even on the day he died, Blake was painting scenes from Inferno, knowing he was fading fast. That takes more dedication to the subject than just striving for a commission.

We, of course, are fascinated with Blake’s original poetry and art from his books Songs of Innocence and of Experience and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. But it’s important to know that he also left us with countless beautiful interpretations of stories that he himself was fascinated by—pieces that he worked on until his dying day, like a true artist—and a true fan.

– Stephanie Grossman

Sources

C. H. Collins Baker. “William Blake, Painter.” The Huntington Library Bulletin, no. 10 (1936): 135-48. doi:10.2307/3818143. www.jstor.org/stable/3818143.

Mulcahy, T. I. “William Blake. Poet and Painter, 1757-1827.” The Irish Monthly 50, no. 594 (1922): 519-26. www.jstor.org/stable/20505964.

Wikipedia contributors, “William Blake,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Blake (accessed March 9, 2017).