“Pictures just come to my mind, and I tell my heart to go ahead.” –Horace Pippin1

We have gathered a selection of the works of African American self-taught artists to honor Black History Month. Through time, the output of Black creators in America has been labeled “primitive,” “naive,” “folk art,” “self-taught,” and more recently, “black vernacular.”2

The common ground for all of these artists is that their work springs from lived experiences, filtered through highly personal lenses, and characterized by the innovative use of found or recycled materials. The lives of these individuals were shaped by a history that ingrained violence, poverty and racism, and excluded access to academic training: Slavery, the challenges of the Restoration, the Great Migration, Jim Crow, and the Civil Rights period mark the works of these artists. The foil to the hardships was intense religious inspiration and the ability to mine the beauty from shared and singular experiences in the family and the community.

Early in the nineteenth century creative expression in Black communities centered on utilitarian objects–quilts, pottery, blacksmithery. These endeavors fell below the high academic classification of “fine art” to the lower tier of craftsmanship in the perceived hierarchy of creativity. While related to self-taught art, the craft tradition is based on apprenticeships and learned skills, a transfer of expertise that departs from the entirely contained process of the autodidact.

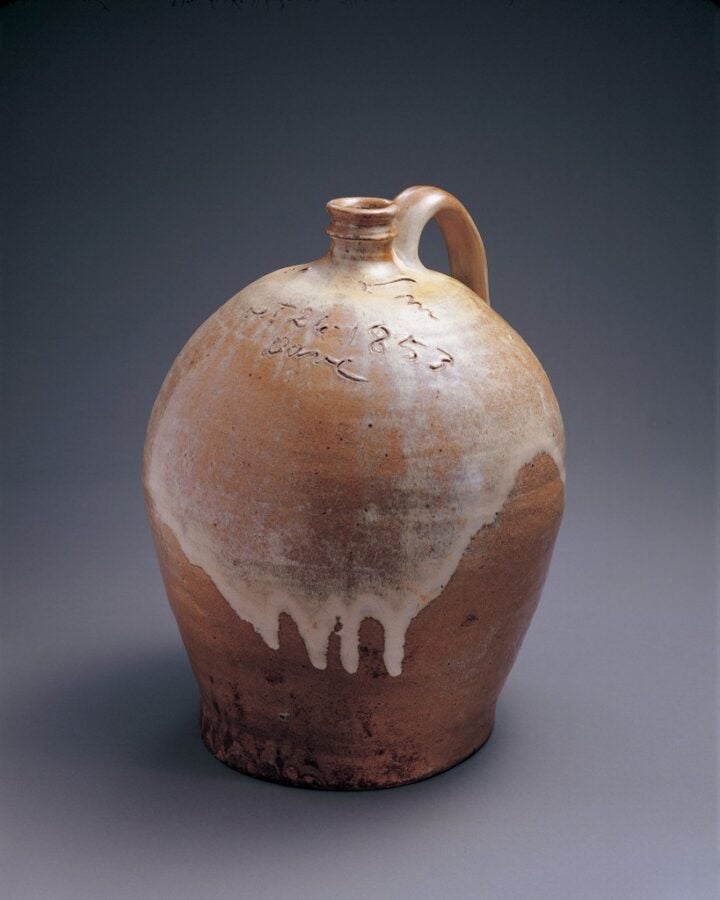

David Drake was an enslaved master potter from South Carolina who is known today for more than 100 glazed jars, some monumental. He is distinctive for the inscriptions he added to the shoulders of the vessels. Some are signed and around 40, called poem jars, include short rhymes. Drake’s inscriptions stand out in direct defiance of the Anti-Literacy Act that was passed in 1834.3

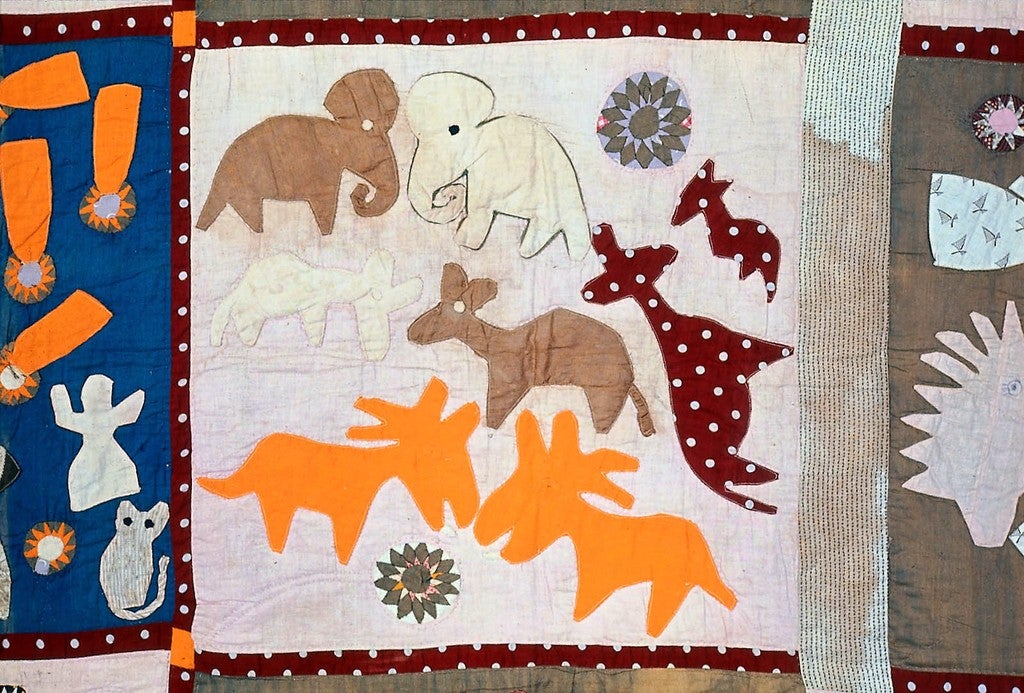

Harriet Powers’s Pictorial Quilt (1895–1898), begotten of her fervent religious faith, her unique vision, and refined needlework skills, raises a practical object to fine art. The story quilt combines 15 narratives, both biblical and worldly, in a patchwork of hundreds of machine and hand-stitched appliqués, in a technique that probably derives from Dahomey, West Africa. Born into slavery, the emancipated artist gave extraordinary pictorial expression to oral storytelling traditions.

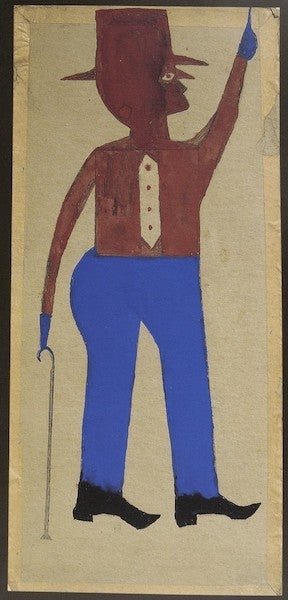

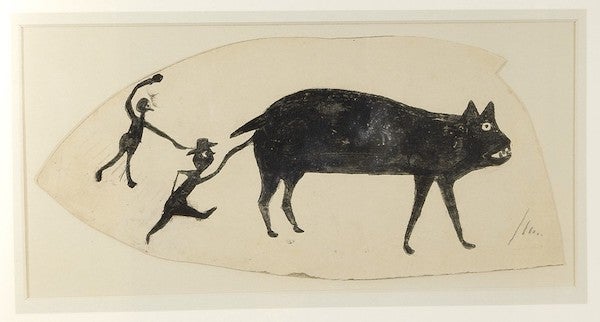

Bill Traylor (c. 1853–1949) is known for approximately 1,500 paintings and drawings. His life marks the point where individual Black artists began to assume identities that were independent of the legacy of craft and tradition. His entire output was produced after the age of 85, made in Montgomery, Alabama, when he left his rural roots behind. His studio was on the street. There, he drew and painted on supports of recycled cardboard advertisements and fragments of boxes with pencils, charcoal, and poster paint. Two paintings from around 1939 show Traylor’s originality—bold, unmixed color, silhouetted, morphing forms and the familiar motifs of a man with a pipe and supersized animals fleeing humans.

The solid sculptures of William Edmonson (c. 1882–1951) diverge from the fluid lines of Traylor’s paintings. Born in Nashville, Edmonson worked many trades before he took up stone cutting in the 1930s and almost accidentally discovered his calling as a sculptor, first making garden ornaments and tombstones. Self-taught but entirely motivated by his faith, he called his sculptures his miracles. After the photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe recorded his work in images like those shown here, he became the first African American self-taught artist to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1937.

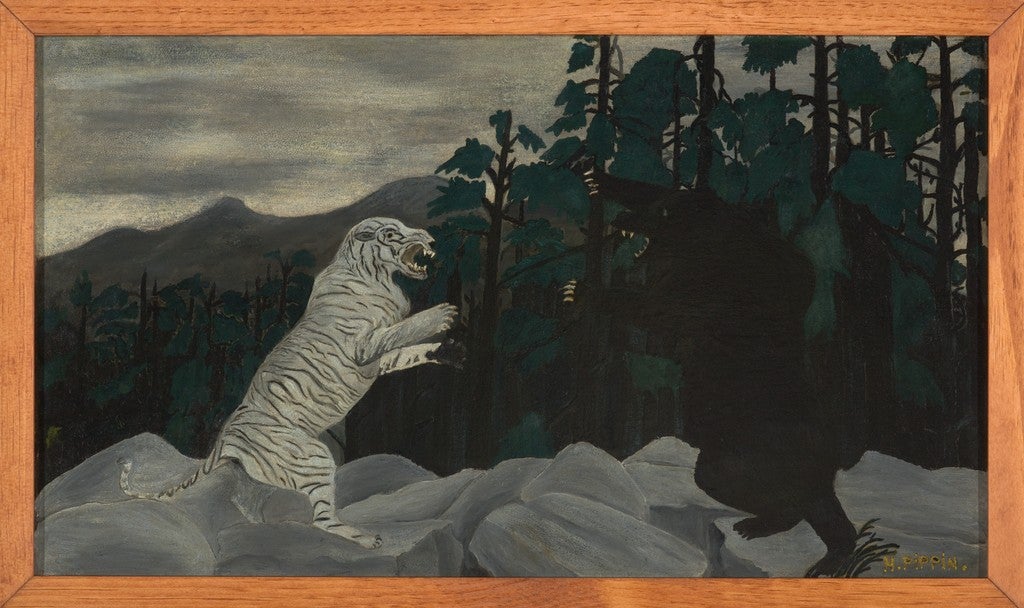

Horace Pippin (1888-1946), born in Pennsylvania and raised in rural New York, returned from duty in WWI with a wound that hindered his right arm. Compelled to paint by his war experiences, he devised a workable technique of burning designs into wood panels and applying color. He later mastered painting and left an oeuvre of about 130 works—history, landscape, genre—most of which he sold and exhibited nationally.

While Pippin’s physical limitations may have restricted the size of his paintings, which are all small in scale, many of the subjects are ambitious and consequential. In addition to “The Whipping,” 1941, illustrated here, the artist painted other histories including “The Prejudice,” a series about the abolitionist John Brown, and recollections of the war.

Native to North Carolina, James Hampton (1909–1964) moved to Washington, where he spent much of his adult life. In his later years, from the 1950s until his death, he devoted himself to the creation of a single, glorious and resplendent work of art dedicated to the second coming of Christ and entitled “The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations’ Millennium General Assembly.” Janitor by day and artist by night, the self-proclaimed “Director, Special Projects for the State of Eternity” immersed himself in the fabrication and adornment of an enormous pulpit with around 180 elements, occupying 300 square feet.

Each piece is made of discarded objects—scrap cardboard, plastic, repurposed furniture, light bulbs, jam jars, electrical conduits—all held together with pins and glue, and glittering beneath a skin of silver and gold foil recovered from the garnishes of bottles, cigarettes, and store displays. The assemblage centers on a throne, flanked on either side by elements from the Old and New Testaments, respectively. The following biblical proverb, written in the hand of the artist, was found pinned to the wall of the garage where he built his heavenly dais: “Where there is no vision, people perish.”4

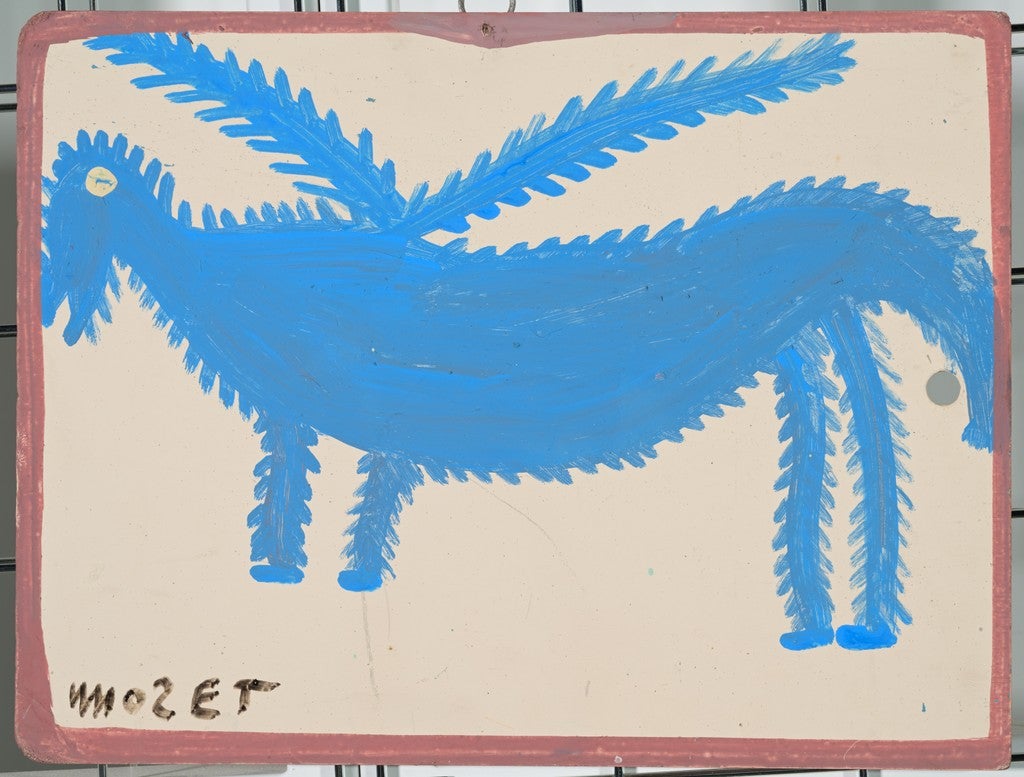

Mose Tolliver (1924–2006) began life in rural Alabama in a large sharecropping family and moved to Montgomery. He turned to painting after an accident in the late 1960s. He was prolific, making up to 10 works a day on cardboard, plywood, furniture board and other recycled surfaces in the preferred medium of house paint, favoring bright, unmixed colors. The fanciful bird motif and the stylized crucifixion seen here recur in his work.

The complex and large assemblages of Thornton Dial Sr. (1928–2016) are rooted in his years in Bessemer, Alabama, where he worked for the Pullman Railcar Company as a pipefitter, constructing and welding, and as a carpenter. These works and his paintings and drawings number in the hundreds and they center on portraits, notably women, visions and parables, and the struggles of his People and the Civil Rights movement.

In Dial’s assemblages, based on a surface of board and canvas, he built a intricate substrate of found objects—clocks, wheels, car parts, stuffed animals, clothing, newspaper, macrame and organic substances—welded, glued, crushed and painted, that spelled the lines, shapes, masses and messages of his imagination. In “Crying in the Jungle, Crying for Jobs,” 1996, 4×6 feet and nearly eight inches deep, the faces emerge from a gray morass linked by lines of painted rope.

Bessie Harvey (1929–1994) fought hardship day by day in her native Tennessee, raising 11 children in poverty with no partner, but she was sustained by her great faith. Her sculptures, shaped from roots, branches, vines, and found objects, and her paintings focused on her religious beliefs and provided an escape from her trials. She described them as mediums for her spiritual and emotional release.

Just as her inspiration came from God, her creative impulse came from nature. She referred to her process of letting the root determine what it “wants to be.” In the case of “Birthing,” c. 1986, her original impulse was to make an old man leaning on a stick but another idea prevailed. The woman giving birth is a likely subject for the artist who raised so many children. However, crowned in glittering silver, she is no ordinary being: She is “an African girl; she’s a queen, and she’s giving birth to a baby.”5

Collections on JSTOR

California College of the Arts: Contemporary Art Project

Center for Creative Photography

Notes

- Judith Stein, “I tell my heart: The story of Horace Pippin,” Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 1993, p. 2. ↩︎

- “Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980,” 1982, an exhibition generated by the Corcoran Gallery of Art and shown at venues across the country, was a turning point for the recognition of Black self-taught artists. For a history of the rise of African American self-taught creators and the evolution of ideas about their work see L. Umberger & D.O. Robson, We Are Made of Stories: Self-Taught Artists in the Robson Family Collection, Princeton University Press (2022), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2hvfj6m. ↩︎

- Like Drake, many Black creators were enslaved; however, a minority of Black artisans like the silversmith Peter Bentzon and cabinet maker Thomas Day were free. ↩︎

- In 1970, the throne was acquired by the Smithsonian American Art Museum. For an introduction, see Leslie Umberger, curator, in James Hampton’s The Throne of the Third Heaven, American Art Moments, 2021. ↩︎

- “The Bessie Harvey Homepage,” quoted in “Bessie Harvey And Her Tennessee Roots,” The Art of The Ritual. ↩︎