As the strength of the sun wanes in the fall, our festivities and rites tend to be centered on the elements of fire and light — natural, divine, and synthetic. It is no accident that many of our brightest celebrations light up our darkest months. Below, we have selected some images that collectively exalt the power of light to animate our revels.

In many cultures the demise of the sunniest season is marked by the glow of the autumn moon and the celebration of the bounty of the fall harvest, kicking off the season of light. Harvest Moon, c. 1833 by the English painter Samuel Palmer is bathed in a lunar glow so bright that the reapers gather their crops by night. The celebration of Diwali (festival of lights) signifying the triumph of good over evil — exemplified by Hindu deities and other traditions of southeast Asia — begins as the last harvest is made in October and November. The magical golden light of fireworks, lamps, and candles, as shown in the sparkling watercolor from Uttar Pradesh, c. 1760, ignites the darkness of the blackened sky.

Hanukkah, celebrated by the Jews between late November and through December, was also associated with the harvest, but its deeper meaning comes from the victory of the Maccabees over the Seleucid king Antiochus. The triumph is also celebrated as light overcoming darkness in the form of the menorah, shown here in a silver version and in a Spanish medieval manuscript illustration. The menorah stands for the miraculous regeneration of the oil that the Maccabees used to fire their menorah when they had reclaimed their Temple.

The Winter Solstice, a pagan celebration also known as Yule (from the nordic word for circle or wheel, symbol of the sun) occurs on the shortest day, December 21, in anticipation of the lengthening rays of the sun, and has been honored from the time of the Romans to modern druids. In a photograph of 2007 by Thomas Pilston, the glowing dawn is fugitive but it heralds the return of the sun as it will slowly reclaim the days. Christmas, which inherits many traditions of Yule, follows on December 25, marking the day of the birth of Christ. A spiritual fire suffuses the nativity scene from Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim altarpiece, c. 1515, while divine light is eclipsed by the electric glow of Rudolph in a contemporary photograph by Chris Steele-Perkins.

Kwanzaa, celebrated by people of African descent in America, comes from the Swahili for “first” and it also relates to the harvest, albeit its earliest rather than latest fruits. From December 26 to January 1, the holiday feasting and gathering are enjoyed with the lighting of the kinara (candle holder) and the mishumaa saba (seven candles) at the symbolic center. A photograph by Bob Gore, 2006, features a woman in a Kwanzaa performance.

In Japan, prior to 1873 when January 1 was adopted as new year’s day, the celebration followed iterations of the lunisolar calendar, beginning in late January, as in China, and was often highlighted by spectacular fireworks. Natural and spiritual displays of light also animate the woodblock prints that celebrate the season. The magical vision of Utagawa Hiroshige in a print from the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, 1856-1858, presents the spectacle of the glowing firefoxes of New Year’s Eve. Each fox in the foreground appears to breathe a little fire (kitsunebi) while dozens more approach with tiny dots of flame — the number of fires would foretell the upcoming rice harvest. In Utagawa’s New Year’s Sunrise, c. 1831, the dawn overtakes the night, announcing the day and the year with a clear, serene light.

May your celebrations sparkle and your new year be bright.

– Nancy Minty, collections editor

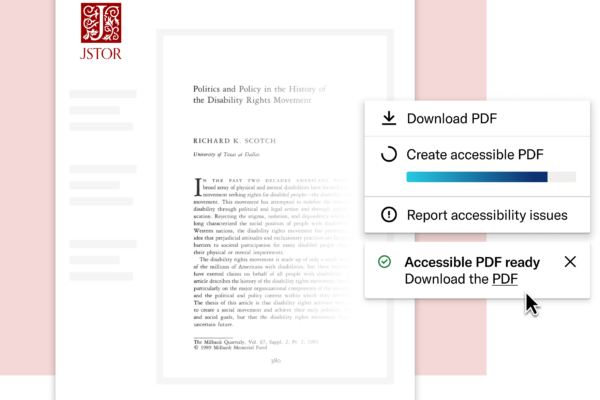

Collections in JSTOR

Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives

The Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism (ARAS)

Bob Gore: Faith-based Communities

From JSTOR Daily